Advertisement

But researchers caution this does not mean low-income families are escaping hardship. And they warn that when the aid expires next month, families could again be vulnerable.

WASHINGTON — An unprecedented expansion of federal aid has prevented the rise in poverty that experts predicted this year when the coronavirus sent unemployment to the highest level since the Great Depression, two new studies suggest. The assistance could even cause official measures of poverty to fall.

The studies carry important caveats. Many Americans have suffered hunger or other hardships amid long delays in receiving the assistance, and much of the aid is scheduled to expire next month. Millions of people have been excluded from receiving any help, especially undocumented migrants, who often have American children.

Still, the evidence suggests that the programs Congress hastily authorized in March have done much to protect the needy, a finding likely to shape the debate over next steps at a time when 13.3 percent of Americans remain unemployed.

Democrats, who want to continue the expiring aid, can cite the effect of the programs on poverty as a reason to continue them, while Republicans may use it to bolster their doubts about whether more spending is needed or affordable.

“Right now, the safety net is doing what it’s supposed to do for most families — helping them secure a minimally decent life,” said Zachary Parolin, a member of the Columbia University team forecasting this year’s poverty rate. “Given the magnitude of the employment loss, this is really remarkable.’’

The Columbia group’s midrange forecast has poverty rising only slightly this year to 12.7 percent, from 12.5 percent before the coronavirus. Without the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act — the March law that provided one-time checks to most Americans and weekly bonuses to the unemployed — it would have reached 16.3 percent, the researchers found. That would have pushed nearly 12 million more people into poverty.

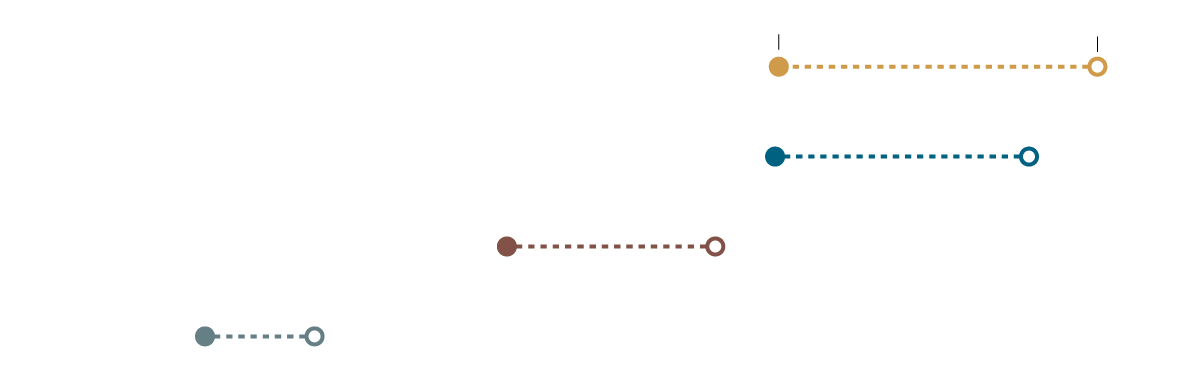

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act is projected to stabilize poverty rates despite the pandemic, according to a study by the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University. Here is how racial and ethnic groups are expected to benefit.

Hispanic

With CARES

Without CARES

With CARES

Without CARES

Hispanic

Under the government’s fullest measure, a typical family of four is considered poor with an income below about $28,000.

The researchers estimate the CARES Act will increase safety net spending this year by $460 billion, more than what the government spent all last year to support the incomes of families that are not elderly.

In a separate study, Bruce D. Meyer and Jeehoon Han of the University of Chicago and James X. Sullivan of Notre Dame, analyzing Census Bureau survey data, found that incomes rose among needy Americans in April, despite cresting unemployment, as government payments began.

They estimate that poverty in April and May fell to 8.6 percent for the previous 12 months, from 10.9 percent in January and February. (They use a different census definition of poverty than the Columbia group.)

“When we initially saw our results, we thought, ‘How could this be true?’” Mr. Sullivan said, given the economic crisis. “But when you look at the size of the government response, it makes sense.”

After losing their jobs, millions of workers have experienced a bewildering mix of hardship, delay and relief. Consider the experience of Melody Bedico, a single mother in Seattle who works as a clerk at an airport hotel.

As travel plunged in March, so did her work hours, until the hotel closed and left her with no income.

Though she immediately applied for unemployment insurance, Ms. Bedico got no help for two months. Multiple calls a day to the Washington state unemployment office went unanswered. Someone once put her on hold for two hours, then cut her off. (She cried.) When food ran short, Ms. Bedico limited herself to two meals a day to feed her 12-year-old daughter. She fell three months behind on her mortgage.

“My whole body really ached with stress, from my head to my toes,” she said.

Then $7,600 suddenly arrived for eight weeks of back benefits, including a $600 weekly bonus. Counting a stimulus payment, Ms. Bedico’s income, $15,500 for three months, is nearly 60 percent more than she would have earned at the hotel.

“I was so happy — I really needed that money,” she said.

The peril has not passed. Though the aid will lift Ms. Bedico’s annual income above the poverty line, she does not know when she will return to work. After the bonus ends next month, her benefits will plummet, leaving her with an income 40 percent lower than normal but facing the same bills. “I’m worried I could lose my house,” she said.

The CARES Act contained three major provisions to bolster incomes. It offered most households one-time payments (up to $1,200 per adult and $500 per child). It broadened unemployment insurance to include millions of gig workers and other nontraditional employees. And it added $600 to weekly unemployment checks through July — a bonus of nearly $11,000 on top of regular payments, for those who qualify all four months.

The effect has been significant. The economist Peter Ganong and two colleagues at the University of Chicago found that among workers eligible for unemployment, two-thirds can collect sums that exceed their earnings. Until the $600 bonus expires, the poorest fifth can at least double their lost pay. While state benefits vary, the median worker is eligible to receive 134 percent of his or her pay.

While few who get the enhanced benefits will fall into poverty, Mr. Ganong warned that some jobless workers were ineligible and that bonuses would expire long before the economy recovered. “This is a strong start but only the first chapter of a long story,” he said.

Poverty rates are based on annual incomes, so families losing aid may suffer new hardship even though the earlier assistance leaves them above the formal poverty line.

Some analysts warn that hardship has grown, even if poverty rates have not. Diane Schanzenbach, an economist at Northwestern University, notes that food insecurity is twice its prepandemic rate and child hunger has risen even more. Part of the hardship may stem from the growth in income volatility — needy families generally lack credit or savings to sustain them through delays.

“A lot of people aren’t seeing the money yet,” Ms. Schanzenbach said. “I’m worried about Congress taking its foot off the gas.”

One person whose income has grown is Sunshine Lopez, 41, a medical assistant in Spokane who left work on a doctor’s advice because her daughter has a compromised immune system. Workers who quit jobs normally cannot collect jobless benefits, but the CARES Act contains a medical exception.

“I had to make a decision between my daughter and my job,” she said.

Fearing delays, she was surprised when help quickly arrived — $840 a week after taxes — more than 50 percent higher than her regular pay. Without the CARES Act, she said, “I probably would have been on the street.’’

Many unemployment offices remain plagued by long delays, with Florida’s system especially overwhelmed. A sophisticated online fraud scheme, which authorities say may be based in Nigeria, has slowed processing in many states. Washington, hit particularly hard, has asked the National Guard to help process claims.

For unemployed workers without jobless aid, times are harder than usual. Carlos Arciga, 53, got fired from an apple-packing warehouse in Yakima, Wash., after missing two days with a fever. He sought jobless benefits and waited for three months until the state said the firing disqualified him.

Normally, he said, he could have found a new job. “I’m a guy who works all the time,” Mr. Arciga said. Now he lives with his parents and survives on food stamps. “I’m in a bad spot — I don’t have a place, and I don’t have any money,” he said.

Undocumented migrants face special risks of falling into poverty, and many have American children. The CARES Act bars an entire household from stimulus payments even if a single member lacks legal status. The Migration Policy Institute estimates that prevents 15.4 million people from receiving aid — about 10 million undocumented migrants and more than five million children and spouses who are legal residents or citizens. Unauthorized migrants are also barred from jobless benefits.

An undocumented woman in Manhattan, who asked to be identified only by her first name, Mercedes, is part of a mixed-status family suffering new hardships. Her partner, who is also undocumented, lost his construction job at the start of the pandemic, and they have received no cash income since. They are raising her 16-year-old and their two children, ages 4 and 2 — all American citizens.

After exhausting $1,500 in savings, they have survived on the children’s food stamps and groceries distributed at school, with adults eating less to keep the children fed. With legal status, the family could have received more than $12,000 in aid. Mercedes called it “a terrible injustice” to treat her children different from other Americans.

“Let people’s hearts be touched — these kids have needs like any other legal person,” she said.

Elizabeth Ruiz, an undocumented restaurant cook in Dallas, does not resent the government excluding her from aid. “It’s their country, their rules,” she said. But her car has been repossessed, and she and her husband, another undocumented worker who lost his job, have relied on groceries and rental assistance from food banks.

“This is the most difficult economic time we’ve lived through, even in Mexico,” she said.

In forecasting poverty, the Columbia researchers — who include Megan Curran and Christopher Wimer — considered three scenarios, depending on what share of eligible workers succeed in getting aid amid the delays. Poverty would rise slightly to 12.7 percent if workers enjoy “medium access” to benefits and fall to 11.3 percent with “high access.” (Workers have already exceeded the “low access” scenario, making it obsolete.)

An earlier forecast they made, which did not account for the CARES Act, warned that poverty could reach the highest level in the half-century for which there is data.

With medium access to benefits, the black and white poverty rates will change little, but the Latino and Asian numbers will rise, partly because of the ban on aid to households with unauthorized immigrants. The projected poverty rates for blacks (20.2 percent) and Latinos (20.3 percent) are more than twice as high as those for whites (8.7 percent), but without the CARES Act, the disparities would have grown even larger. For Asians, the poverty rate is 14.5 percent.

While applauding the effect of federal aid to date, the Columbia researchers emphasize the importance of continuing it. “What we’re doing has been largely successful, but families could find themselves in big trouble in the fall after it expires,” Mr. Wimer said.

Mr. Meyer of the University of Chicago is less certain of future need. “The payments have worked so far, but I wouldn’t commit to spending more than a couple months out because we don’t know how quickly the economy will recover,” he said.

Mr. Ganong praised the CARES Act for restraining poverty among minorities at a time of elevated concern about racial injustice. “You can think about it as addressing many of the economic issues raised by Black Lives Matter,” he said.

While many people endured delays, Trina Harris experienced the opposite — unemployment checks came quickly, then stopped without explanation. A housekeeper in a Seattle hotel, Ms. Harris, 49, earns $18 an hour while raising a daughter and a grandson with special needs.

The jobless benefits she received, added to her stimulus check, more than doubled her normal income for six weeks. Then the check was replaced by a computer message that said “pending.”

Ms. Harris is so frugal she had taxes taken out of her jobless benefits and set aside money for the rent — a special focus of anxiety. (“I always — always — pay the rent.”) She is so worried about becoming homeless that when her grandson talks to a counselor online, “I slip my own issues in there, too.”

After 22 years at the same hotel, Ms. Harris said, “I’m not looking for no free ride,” but said of the CARES Act, “we needed that help.”