Compared to center-right parties in developed democracies, the GOP is dangerously far from normal.

The Republican Supreme Court power grab after Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death should be shocking, given the naked hypocrisy involved. The only reason it isn’t is that we’ve come to expect this from Republicans — and not just under Trump.

Republicans shut down the government in the 1990s and impeached President Bill Clinton over far less than what Trump has done in office. Under Obama, they fanned the flames of birtherism, held the global economy hostage to force spending cuts, and elevated obstructionism to the level of governing principle.

At the state level, they have rewritten electoral rules to block Democrats from voting and seized power from Democratic governors after they have won elections. Just this week, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis proposed a bill that would effectively criminalize anti-police violence protests — and protect drivers who ran over protesters with their cars.

This kind of radicalism is not at all normal — at least, when compared to center-right parties in other advanced democracies.

Experts on comparative politics say the GOP is an extremist outlier, no longer belonging in the same conversation with “normal” right-wing parties like Canada’s Conservative Party (CPC) or Germany’s Christian Democratic Party (CDU). Instead, it more closely resembles more extreme right parties — like Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz in Hungary or Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP in Turkey — that have actively worked to dismantle democracy in their own countries.

The Supreme Court saga can’t be considered in isolation. It is symptomatic of a profound brokenness in American politics, one party dragging us away from the developed-world political standards we aspire to and towards a fight over the most basic of democratic principles: whether power should be shared. And that’s a disaster for American democracy.

“The only way we move forward is when Republicans reform, and cease to be an increasingly authoritarian white nationalist party,” says Steven Levitsky, a Harvard professor and the co-author (with Daniel Ziblatt) of How Democracies Die.

The Republican Party really is different

Levitsky’s views are not at all an outlier.

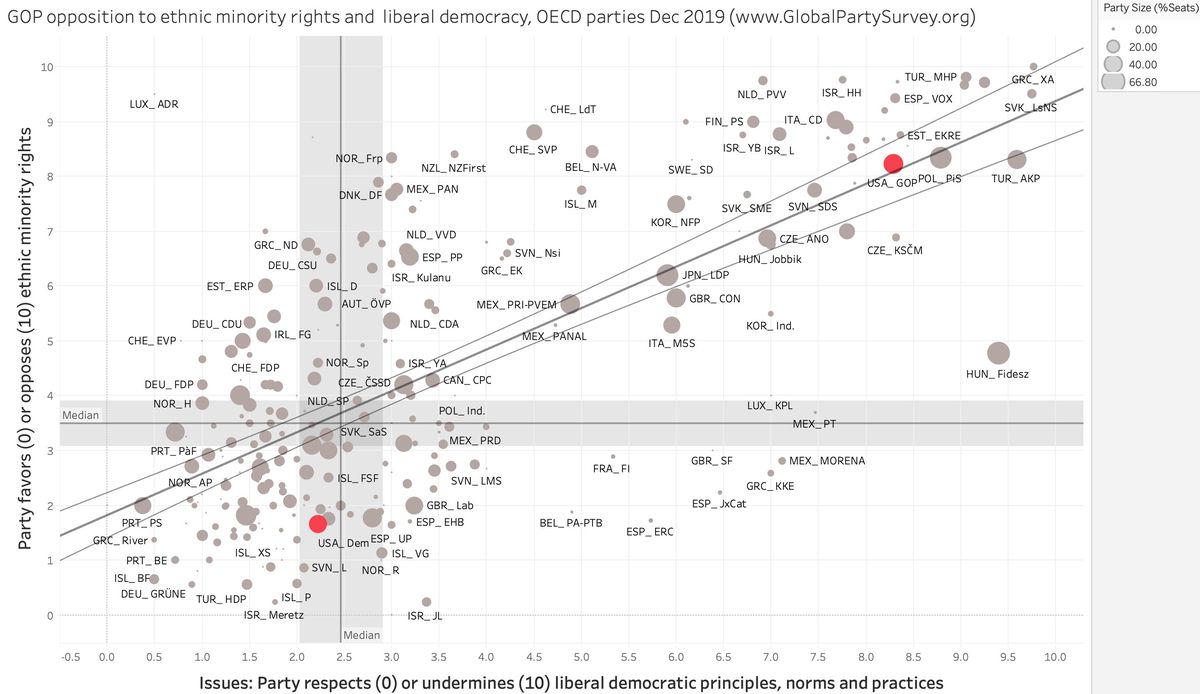

A 2019 survey of nearly 2,000 experts on political parties from around the world asked respondents to rate political parties on two axes: the extent to which they are committed to basic democratic principles and their commitment to protecting rights for ethnic minorities. The higher the number, the more anti-democratic and intolerant the party is.

The following chart shows the results of the survey for all political parties in the OECD, a group of wealthy democratic states, with the two major American parties highlighted in red. The GOP is an extreme outlier compared to mainstream conservative parties in other wealthy democracies, like Canada’s CPC or Germany’s CDU.

Its closest peers are, almost uniformly, radical right and anti-democratic parties. This includes Turkey’s AKP (a regime that is one of the world’s leading jailers of journalists), and Poland’s PiS (which has threatened dissenting judges with criminal punishment). Experts rate the GOP as substantially more hostile to minority rights than Hungary’s Fidesz, an authoritarian party that has made demonization of Muslim immigrants into a pillar of its official ideology.

In short, there is a consensus among comparative politics scholars that the Republican Party is one of the most anti-democratic political parties in the developed world. It is one of a handful of once-centrist parties that has, in recent years, taken a turn toward the extreme.

“The transformation of the GOP is in line with other transformations of conservative into far-right parties, like Fidesz in Hungary,” said Cas Mudde, an expert on right-wing politics at the University of Georgia.

Over the past decade and a half, Republicans have shown disdain for procedural fairness and a willingness to put the pursuit of power over democratic principles. They have implemented measures that make it harder for racial minorities to vote, render votes from Democratic-leaning constituencies irrelevant, and relentlessly blocked Democratic efforts to conduct normal functions of government.

According to Jennifer McCoy, a political scientist at Georgia State University, these measures follow common patterns seen among populist authoritarians who initially win power by electoral means. They tend to pass changes to the electoral system aimed at ensuring “one party dominates government” while also working to marginalize or control “accountability institutions” like the judiciary or oversight watchdogs.

“Many of these leaders are able to do so when they first win a clear majority and then begin to change rules or the constitution to further entrench their advantage and get to supermajorities,” McCoy tells me.

For Republicans, the process of moving toward anti-democracy has taken decades rather than a single election. There was never a single unified GOP plan to lock out Democrats, akin to the way that Fidesz intentionally remade the Hungarian political system after winning the country’s 2010 election. There is no authoritarian plot behind the GOP’s recent maneuvers, and no secret plan to end elections or declare martial law.

What there is, instead, is systematic disinterest in behaving according to the democratic rules of the game. The GOP views the Democrats as so illegitimate and dangerous that they are willing to employ virtually any tactic that they can think of in order to entrench their own advantage. This is perhaps the party’s core animating ideology, at every level: we must win because the Democrats cannot be given power.

You can see the effects of this idea most clearly on the state level, where most of the action of election administration happens in American systems. In a forthcoming book chapter with Murat Somer, a scholar at Turkey’s Koç University, McCoy describes clear evidence that “Republican-led states [are] more likely to support anti-democratic measures, including failing to respond to democratic mandates from the public, curbing political participation, using policy to tilt the electoral playing field in one’s favor, and rejecting progressive policies approved by municipalities.”

For example, Republicans won about 50 percent of the US House vote in North Carolina in 2018’s election. That translated into 70 percent of House seats due to heavily gerrymandered districts. Wisconsin Democrats won every statewide election in 2018 but did not win majorities in either chamber of the state legislature. While Democrats are also at a disadvantage due to concentration in urban areas, gerrymanders share much of the blame.

North Carolina Rep. David Lewis, who chaired the state redistricting committee that put together a map so racially contorted that it was struck down in court in 2016, openly professed the power politics behind extreme gerrymandering in a speech on the statehouse floor.

“I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats,” he explained. “So I drew this map in a way to help foster what I think is better for the country.”

Lewis is notable mostly for his unusual honesty. Republicans believe they ought to win elections, and are doing everything in the power to make that the case — including changing the rules to stack the playing field in the favor. The effect is a party committed to an anti-democratic creed outside the norm of advanced Western democracies that insists that it is the true guardian of American democracy.

Any effort to fix American politics needs to be clear-eyed on this point: The Republican Party is so beyond what’s normal in a healthy democracy that some kind of radical pro-democracy reform is required — be it ending the filibuster, court-packing, DC and Puerto Rico statehood, a new Voting Rights Act, or all of above — to try and turn things around.

“The Republicans pose too much of an authoritarian threat,” Harvard’s Levitsky tells me, “to simply go on with business as usual.”

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

The United States is in the middle of one of the most consequential presidential elections of our lifetimes. It’s essential that all Americans are able to access clear, concise information on what the outcome of the election could mean for their lives, and the lives of their families and communities. That is our mission at Vox. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone understand this presidential election: Contribute today from as little as $3.