Let’s start with a plausible scenario that could play out in the 2020 election.

Democrats win the popular vote by an even wider margin than Hillary Clinton’s nearly 3 million vote lead in 2016, running up the score in solid blue states and closing most of the gap in large red states like Texas. Pennsylvania and Michigan return to the Democratic fold, but Trump ekes out the narrowest of victories in Wisconsin. He walks away with exactly 270 electoral votes and the presidency.

Meanwhile, House Democrats have a strong year, but not nearly as strong as 2018. Democratic candidates win every congressional district where Hillary Clinton prevailed in 2016, plus every district where Clinton lost by less than 3 percentage points. Democratic House candidates win the total popular vote by a few percentage points, but it’s not enough. Despite her party’s popular vote victory, Speaker Nancy Pelosi is once again demoted to minority leader.

In the Senate, Democrats pick up seats in Colorado and Maine, but they never really have a shot at replicating Sen. Doug Jones’s fluke win in Alabama. Republicans end up with a 52-seat majority in the Senate — and, with it, the ability to keep filling the courts up with Trump judges. Although the Democratic “minority” would represent about 17 million more people than the Republican “majority” in this scenario, Mitch McConnell still controls the Senate.

Solid majorities of the nation, in other words, could vote for a Democratic White House, a Democratic House, and a Democratic Senate, and yet Republicans could gain control of all three.

The system is rigged. It was rigged from the outset, quite intentionally, to favor small states. Under current political coalitions, that’s become an enormous advantage for Republicans. The country’s framers obviously could not have known that they were creating a system that would give Donald Trump’s party an unfair advantage over Hillary Clinton’s party more than two centuries later. But they did create a system that favors small states over large states.

That means that a political coalition that is largely powered by voters in dense, urban areas — like, say, modern-day Democrats — are at a terrible disadvantage under this constitutional arrangement. (And, to be clear, the system would be just as anti-democratic if it put Republicans at a disadvantage instead.)

Republicans, meanwhile, take their unfair advantage and build on it by gerrymandering the states they control, using their Senate “majority” to fill the courts with Republican judges, and then using their control of the judiciary to bolster their own party’s chances in elections.

This is how United States now finds itself barreling toward a legitimacy crisis.

Four features of our anti-democratic democracy

Broadly speaking, there are four features of our system of government that make our democracy less democratic, many of them working in interlocking ways. These features also happen to give the GOP a structural advantage.

1) The Senate is deeply unrepresentative of the country

According to 2018 Census Bureau estimates, more than half of the US population lives in just nine states. That means that much of the nation is represented by only 18 senators. Less than half of the population controls about 82 percent of the Senate.

It’s going to get worse. By 2040, according to a University of Virginia analysis of census projections, half the population will live in eight states. About 70 percent of people will live in 16 states — which means that 30 percent of the population will control 68 percent of the Senate.

Currently, Democrats control a majority of the Senate seats (26-24) in the most populous half of the states. Republicans owe their majority in the Senate as a whole to their crushing 29-21 lead in the least populous half of the states. Those small states tend to be dominated by white voters who are increasingly likely to identify with the Republican Party.

Senate malapportionment is a relic of an unstable alliance among 13 young nations. As Yale law professor Akhil Amar explains, the Articles of Confederation that preceded the Constitution were “an alliance, a multilateral treaty of sovereign nation-states.” The Constitution did not simply change the rules that governed an existing nation; it bound 13 independent and sovereign states together.

The Founding Fathers came together at Philadelphia to achieve union at nearly any cost, because they wanted to avoid the persistent warfare that plagued Europe. Without a union, Amar says, “each nation-state might well raise an army, ostensibly to protect itself against Indians or Europeans, but also perhaps to awe its neighbors.”

Nor was this merely a hypothetical concern. When large states proposed a fair legislature, where each state would be given seats proportional to its population, Delaware delegate Gunning Bedford literally threatened that his state would make war on its neighbors. “The large states dare not dissolve the Confederation,” Bedford insisted, or else “the small states will find some foreign ally of more honor and good faith.”

This is why we have a Senate: In a negotiation among 13 sovereign nations, each of these nations may demand equality as the price of union. Whatever the wisdom of this devil’s bargain in 1787, America is a very different place today. There is little risk that Utah will make war on Colorado, or that New Hampshire will invade Vermont.

Instead, we are heading toward a future where — barring some kind of major partisan realignment — the Senate will routinely feature a majority that represents far less than half of the nation as a whole. In the current Senate, the Republican “majority” represents about 15 million fewer people than the Democratic “minority.” And if current trends continue, the Republican advantage is likely to grow.

A common defense of our current arrangement is that Senate malapportionment wards off a “tyranny of the majority.” As the Heritage Foundation’s Edwin Feulner argues in a piece that’s fairly representative of Senate defenders, malapportionment “keeps less-populated states from being steamrolled.”

But there’s no reason to believe that residents of small states, as a class, make up a coherent interest group whose political concerns are in tension with residents of large states. The residents of Vermont (population: 623,989) vote more like the residents of New York (population: 19,453,561) than they do like the residents of Alaska (population: 731,545). The people of Wyoming (population: 578,759) vote more like the people of Texas (population: 28,995,881) than they do like the people of Delaware (population: 973,764).

There are over 20,000 more farms in California than there are in Nebraska. There are rural regions in large states. And there are some urban centers in small states.

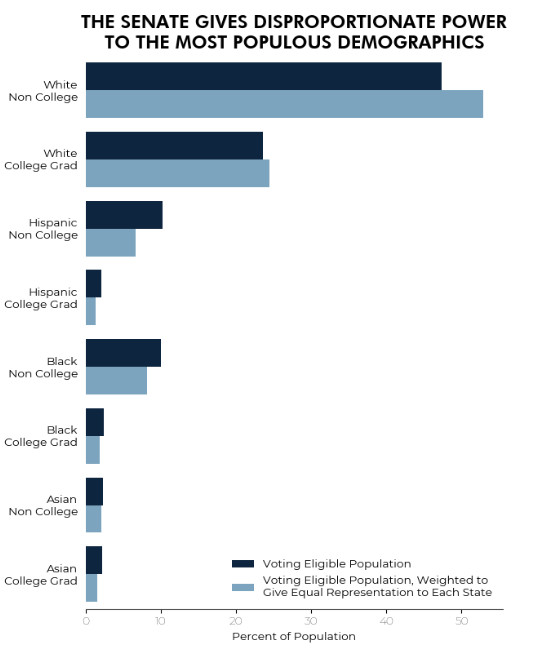

There’s another factor to consider when thinking about the small state advantage: race. The Senate does not simply give extra representation to small states, it gives the biggest advantage to states with large populations of white, non-college-educated voters — the very demographic that is trending rapidly toward the GOP.

Data for Progress

Data for ProgressRepublican dominance of the Senate is a relatively recent occurrence; Democrats, after all, held a supermajority in the Senate as recently as 2009. Yet the GOP’s dominance is also likely to remain durable for as long as many white voters continue to sort into the Republican Party. The Democratic supermajority in 2009 was made possible by Democratic senators in places like Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota. It’s tough to imagine any of those states electing a Democrat so long as America’s current political coalitions remain stable.

Of course, Democrats could try to buck this trend by becoming more like Republicans. They could shift their positions to appeal to the whiter, more socially conservative voters that dominate many of the smaller states. But that’s hardly a solution for the majority of voters that support the Democratic Party’s current positions, who would become even more isolated from power.

And there’s one other point that’s worth making here. Two years ago, Neil Gorsuch made history, becoming the first member of the Supreme Court in American history to be nominated by a president who lost the popular vote and confirmed by a bloc of senators who represent less than half of the country. The second was Brett Kavanaugh.

Similarly, Senate malapportionment also allowed Republicans to hold the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s vacant seat open until Trump could fill it. When Scalia died in 2016, Republicans had a 54-46 majority in the Senate, despite the fact that Democratic senators represented about 20 million more people than Republicans in 2016.

Malapportionment, in other words, does not simply give Republicans an undemocratic advantage in the Senate. It also gave them control of the courts.

2) The next winner of the Electoral College could lose the popular vote by as much as 6 percentage points

The best case for the Electoral College was offered by Alexander Hamilton in the Federalist Papers. The choice of a president, Hamilton wrote, “should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station.” Such a process, Hamilton assured us, “affords a moral certainty” that “the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.”

Hamilton’s argument is refuted by three words: “President Donald Trump.”

Setting aside the fact that the Electoral College is the reason why a man who is not in any degree endowed with the requisite qualifications is in the White House, the Electoral College is not capable of achieving Hamilton’s stated goal. The people who make up the Electoral College are rarely “men most capable of analyzing” who would be an excellent president. They are typically partisan loyalists, selected by their party to perform one and only one task — robotically voting for whoever the party nominated to be president.

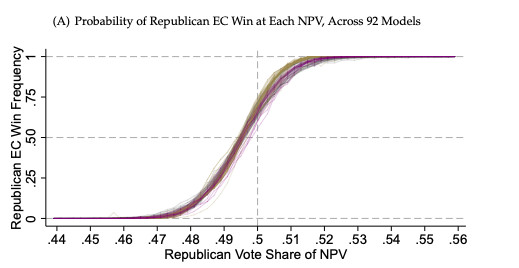

To date, this system has allowed five men who lost the popular vote to become president— Trump, George W. Bush, Benjamin Harrison, Rutherford B. Hayes, and John Quincy Adams. Barring a political realignment, it’s likely that such “inversions” will become more common (as they already have in the past couple decades). A recent study by three researchers from the University of Texas found that “a 3.0 point margin favoring the Democrat (i.e., 48.5% Republican vote share, or a gap of about 4 million votes by 2016 turnout) is associated with a 16% inversion probability.”

In other words, a Democrat could potentially win the popular vote by as much as 6 percentage points and still lose the Electoral College to a Republican.

Michael Geruso, Dean Spears, and Ishaana Talesara

Michael Geruso, Dean Spears, and Ishaana TalesaraA more modern defense of the Electoral College is similar to the conservative defense of the Senate. The Electoral College, according to Heritage’s Hans von Spakovsky, “prevents candidates from winning an election by focusing only on high-population urban centers (the big cities), ignoring smaller states and the more rural areas of the country.”

But if ensuring that candidates focus on the nation as a whole is the goal, the Electoral College defeats this goal. Thanks to the Electoral College, candidates focus almost exclusively on a handful of swing states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, or Michigan, while solid red states and solid blue states are largely ignored.

The real reason why the Electoral College exists is hotly contested. Some scholars, such as Amar and Harvard historian Jill Lepore argue that, in Lepore’s words, the Electoral College “was a compromise over slavery.”

This theory points to the Three-Fifths Compromise, which allowed slave states to count each slave living within their borders as three-fifths of a person for purposes of determining how many representatives those states should receive in the House. Because states gain electoral votes as they gain representation in the House, the Three-Fifths Compromise inflated slave states’ ability to choose a president.

Another theory, recently offered by political scientist Josep Colomer at the Monkey Cage, is that the framers never intended for the Electoral College to choose presidents. They merely expected the Electoral College to whittle down the list of candidates.

Under the original Constitution, the Electoral College would vote on who its members believed should be president. But, if no candidate received a majority, the House would choose the president from among the five candidates who received the most votes.

According to Colomer, “delegates in Philadelphia expected states would put forward a variety of candidates; none would win a national majority in the electoral college; and the election would typically pass to the House of Representatives.” The framers’ error was that they “didn’t expect candidates to emerge and run nationwide.”

So the Electoral College was either a poorly designed kludge that failed to achieve its intended purpose, or a misbegotten device intended to preserve a great evil.

3) Partisan gerrymandering is still allowed

As mentioned above, Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh owe their jobs to Senate malapportionment and the Electoral College — and Republicans owe their dominance of the judiciary to these two men. That dominance, in turn, has profound implications for who controls the House of Representatives.

Gerrymandering, to be clear, is not a uniquely Republican sin. When the Supreme Court took up the question of whether partisan gerrymandering violates the Constitution earlier this year, it heard two cases. One involved a Republican gerrymander in North Carolina, the other a Democratic gerrymander in Maryland.

But states must redraw their legislative maps every 10 years, shortly after the completion of the decennial census. This means that if one party dominates in an election year ending in a zero — as Republicans did in 2010 — that party will get to gerrymander a disproportionate number of states. Large swing states like Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania drew maps that locked Republicans into power in the state legislature. Their control over the state legislatures then gave the GOP an unfair advantage in the US House.

Some of these gerrymanders have since been weakened or dismantled by courts. But the legacy of others will persist into the 2020 election — and potentially beyond — thanks to the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), in which the Court ruled it can’t stop partisan gerrymandering. Rucho, it is worth noting, did not even attempt to defend partisan gerrymandering on the merits — indeed, it described it as “incompatible with democratic principles.”

Nevertheless, a majority of the justices believed that federal courts should not even consider challenges to partisan gerrymandering because they believed that the task of devising a legal test that could sort illegal gerrymanders from permissible maps is too difficult.

In Rucho, all five of the Court’s Republicans voted that federal courts are powerless to stop partisan gerrymandering. All four Democrats agreed that, at the very least, courts should dismantle the most egregious gerrymanders.

Again, Republicans owe that five-justice majority to Senate malapportionment and the Electoral College. Without these two anti-democratic features of our Constitution, it is likely that, at the very least, the most aggressive partisan gerrymanders would also be forbidden.

4) The Constitution is virtually impossible to amend

And that brings us to the last way that the Constitution is anti-democratic — it is almost impossible to amend it in order to remove these defects.

The United States Constitution, according to University of Texas law professor Sanford Levinson, “is the most difficult to amend or update of any constitution currently existing in the world today.” It takes three-quarters of the states to ratify constitutional amendments — which means that Republicans will almost certainly be able to block any attempt to remove the Constitution’s anti-democratic features.

Now, in fairness, there are good reasons why a constitution should not be too easy to amend. The Constitution’s difficult amendment process prevents a transient majority from coming into power, and then enacting a raft of amendments that entrench themselves in leadership.

But a difficult amendment process is only a virtue if the Constitution’s underlying structures are, themselves, conducive to democracy. If those structures become hostile to democracy — or if they tend to cement a minority faction in power — a difficult amendment process prevents the nation from replacing those flawed structures with a more democratic system.

Democrats can resort to nuclear tactics. If Democrats somehow manage to overcome the odds and capture Congress and the White House, they could divide large blue states like California and New York up into several states (provided that the legislatures of those states agreed to such an arrangement), thus changing the makeup of the malapportioned Senate. They could also add new seats to the Supreme Court to cancel out the GOP’s treatment of Obama Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland.

But such moves invite retaliation if Republicans regain control. If there can be 10 Californias, why not 50 Alabamas?

Realistically, the most democratic solutions, such as abolishing the Senate or replacing it with a body that fairly represents all Americans, are off the table in a nation that cannot amend its Constitution. And so we’re likely left with our undemocratic system for a long while, pushing for reform when and where possible, but likely unable to fix the system absent a major political realignment.