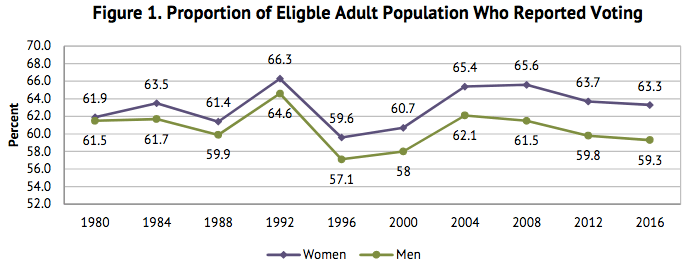

In close elections, Republicans are favored to win even when they lose the popular vote.

In 2016, Donald Trump won the presidency despite receiving nearly 3 million fewer votes than Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton. In 2000, George W. Bush pulled off a similar trick. According to a new study, these are not flukes. They are the kind of results we should expect from the Electoral College.

The study, by three economics researchers at the University of Texas, quantifies just how often the Electoral College will produce an “inversion” — that is, an election where one candidate wins the popular vote but the other walks away with the presidency. The numbers are simply astonishing.

In modern elections where one party prevails by just 2 points in the two-party popular vote, “inversions are expected in more than 30% of elections.” That number rises to 40 percent in elections with a 1 percentage-point margin.

Republicans, moreover, are far more likely to benefit from an inversion than Democrats. “In the modern period,” the study suggests, “Republicans should be expected to win 65% of Presidential contests in which they narrowly lose the popular vote.”

This Republican advantage can shift elections where the Democrat was a fairly clear winner in the popular vote. “A 3.0 point margin favoring the Democrat,” the study concludes, “is associated with a 16% inversion probability.” In other words, Republicans will win nearly one in six presidential races where they lose the popular vote by 3 points.

Indeed, to understand the magnitude of the GOP’s advantage in the Electoral College, consider this chart:

Michael Geruso, Dean Spears, and Ishaana Talesara

The chart shows the probability of a Republican Electoral College victory across 92 different models. Notice that the chance of a GOP victory reaches 50 percent when Republicans have less than 50 percent of the vote. At the extremes, the chart suggests that there is still a small chance of a Republican victory even in elections where Democrats win the popular vote by about six points.

The study is authored by University of Texas at Austin economics professors Michael Geruso and Dean Spears, and Geruso’s research assistant Ishaana Talesara, who is also a student at UT Austin.

To reach their conclusions, the research team ran hundreds of thousands of simulated elections under various election models. The paper as a whole studies three periods in American history: the Antebellum period from 1836 to 1852, the Reconstruction period from 1872 to 1888, and the modern period from 1964 to 2016 (although many of their modern samples only look at the period from 1988 to 2016). These periods were selected to exclude eras when one party typically won in a landslide.

Overall, they conclude that “the high probability of inversion at narrow vote margins is an across-history property of the Electoral College system.” The Electoral College has, at various times, given an advantage to Democrats, Republicans, and the now-defunct Whig Party. Now it gives a clear advantage to Republicans.

The Electoral College skews elections by giving a structural advantage to small states. Each state receives a number of electoral votes equal to the number of United States House of Representatives members from that state, plus two. These two additional votes effectively triple the voting power of the smallest states, while having only a negligible impact on the voting power of large states.

Additionally, modern-day Democrats are disadvantaged because they “have tended to win large states by large margins and lose them by small margins.” In 2016, for example, Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton won California by nearly 3.5 million votes. Meanwhile, she lost the crucial swing states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin by fewer than 80,000 votes combined.

It’s not hard to imagine 2020 producing an even starker inversion. Historically red states like Texas and Arizona are trending toward Democrats, but most likely not enough to flip those states in the next election. If Democrats narrow Trump’s margins in those states, while Trump barely holds onto states like Florida or Wisconsin, the next Democratic candidate could win the popular vote by 5 million votes or more — and still lose the Electoral College.