New analysis found that a college’s reopening decision for the fall term is tied to the red or blue shade of its state, even if political pressure may not be direct.

Colleges and universities looked at several factors when determining whether to reopen their campuses to students for the fall, including local COVID-19 case numbers, campuses’ ability to physically distance students and what students said they wanted in surveys.

But another factor seems to have played a major role in the decision-making process, one that is not being touted in news releases or letters to the community: colleges’ decisions appear to be closely tied to whether the state they are in is red or blue.

Data from Ad Astra’s College Crisis Initiative was able to predict the likelihood of whether an institution planned to be in-person or predominantly in-person for the fall term based on the political leanings of the state.

“In an ideal world, perhaps it shouldn’t matter whether there’s a D or an R after your governor’s name,” said John Barnshaw, vice president of research and data at Ad Astra, which provides scheduling software and consulting services to institutions of higher education. “But it seems to matter, for better or for worse.”

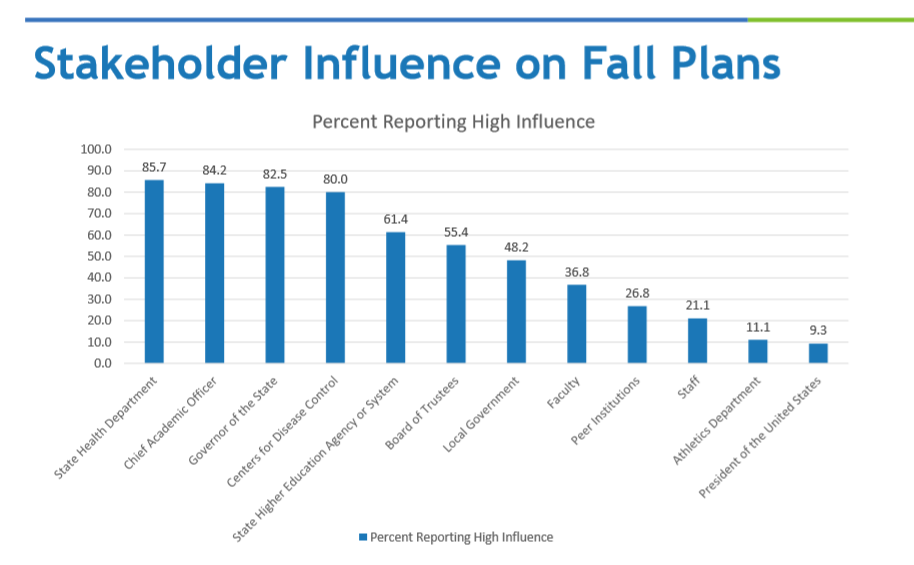

The influence may not be overt, though. A survey Ad Astra sent out to 3,500 institutions asked about the largest influences on fall plans for institutions. The largest influence was the state health department, and No. 3 was the governor.

“Does that mean that she or he directly reached out to a registrar or a chief academic office and said, ‘I want you open’? Probably not,” Barnshaw said. But most governors have communicated their preferences for reopening.

“Does that mean that she or he directly reached out to a registrar or a chief academic office and said, ‘I want you open’? Probably not,” Barnshaw said. But most governors have communicated their preferences for reopening.

“Systems and institutions are looking at that,” he said. “It does have an influence, but it’s not necessarily direct.”

That’s also what Alisa Fryar, professor of higher education and administration at the University of Oklahoma, thinks could be the case.

Fryar hasn’t seen a lot of pressure from elected officials, but she thinks other state-level decisions, like mask mandates, could be cues for college leaders.

“There are a lot of things about relationships between public institutions and political leaders and pressures that are not totally explicit and not completely happening in a public space,” she said. “A lot of the time, I think it’s a complicated dance where institutional leaders are trying to guess at how their decisions are going to be interpreted and whether they will be rewarded or penalized for those decisions.”

The Trump administration has overtly pressured higher education, though. Lobbyists have been concerned that additional federal aid for colleges could be tied to reopening, and officials in the administration have pushed states to reopen campuses, even as cases climb.

Any local or state political influence appears to be a different story. Faculty, board members and administrators at several colleges and university systems told Inside Higher Ed that they didn’t believe politics was a large factor in the decision-making process for fall. But the data show some influence, although it may be subtle.

Barnshaw analyzed Ad Astra’s data on 3,500 institutions. He looked at the potential influence of other factors on colleges’ decisions, but none seemed to match the significance of political control of the state.

If the state was carried by President Trump in the 2016 election, colleges in that state are significantly more likely to have planned more in-person instruction in the fall. This is also true for states with Republican governors and Republican control of legislatures. Colleges in states with a trifecta of a governor, state senate and house all under control of the Republican Party are even more likely to be in person.

The inverse also is true — colleges in states with Democratic governors or legislative control are more likely to offer remote instruction.

Another significant factor is the size of the institution. The larger the college, the more likely it is to be online.

Barnshaw also looked at the number of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people in the state. This factor wasn’t significant in most models. Colleges in states with very high case numbers were more likely to be online, he said, but that factor did not reduce the influence of the state’s politics.

Institutional accreditation and the specific accreditor, as well as the type of governing board for the state higher education system, were also not significant in most models.

The findings are representative of the politically partisan times that society faces, Barnshaw said.

“For our part, Ad Astra works with more than 500 colleges and universities in deep red states, purple states and deep blue states,” he added in a statement. “Our goal remains the same: what can we do better [to] understand the conditions on the ground in each state, and once we have that understanding, how can we help those institutions? I’m proud that when the semester began (August 15), the institutions that partnered with Ad Astra were 15 percent more likely to have a plan and be ready to announce that plan than all other institutions in higher education.”

Public education is inherently a political endeavor, said Robert Anderson, president of the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. Colleges have to interact with state legislative committees and the governor’s staff.

But that doesn’t mean colleges are making plans based on politics, he said. While Anderson was not surprised by Ad Astra’s findings, he cited some gray areas in interpreting them.

“What I’m hearing is the concern from states that this pandemic could last for some time,” he said. “We have to try to prepare for what is the new normal.”

If colleges don’t have the resources or infrastructure to do online instruction well, they need to think about how to best move forward with in-person instruction, he said. Many students are also saying they want an on-campus experience. Equity concerns also are a factor, as some students don’t have access to technology that’s sufficient for online learning.

On top of that are budget issues, like how to pay for residence halls if they aren’t being used, he said.

“To expect this quick pivot to online delivery isn’t very realistic, particularly in a time of budget cuts,” said Anderson.