Long before Michael Bloomberg set his sights on California’s presidential primary, the former New York City mayor used his massive fortune to shape the state’s politics, investing huge sums on campaigns ranging from sugary soda taxes to under-the-radar school board races.

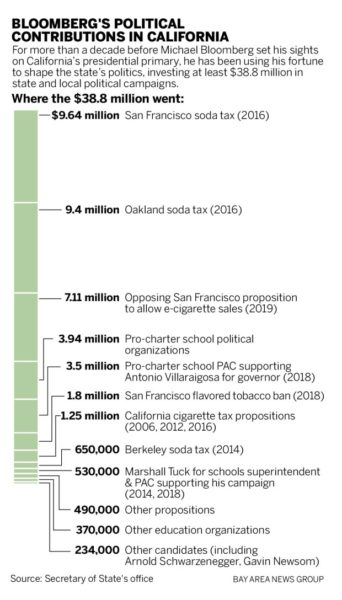

Bloomberg has spent at least $38.8 million on California campaigns, most in the last eight years, according to state and local campaign finance records compiled by the Bay Area News Group. He’s bankrolled efforts to raise cigarette and soda taxes, groups advocating for charter schools, and politicians from both parties, including Govs. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican.

That spending record is helping Bloomberg build connections with key activists and strategists in the state as he makes his long-shot presidential bid in the March 3 primary.

“It’s going to open all sorts of doors for him in California and around the country that simply wouldn’t be available to most candidates,” said Dan Schnur, a political strategist who got a donation from Bloomberg during his own run for Secretary of State in 2014. “Political donations aren’t going to buy anyone’s endorsement, but it certainly creates a relationship that can be beneficial.”

Still, some of Bloomberg’s past spending — especially his record of giving more than $7 million to California groups associated with the charter school movement — could be controversial among the Democratic voters he needs to convert.

Still, some of Bloomberg’s past spending — especially his record of giving more than $7 million to California groups associated with the charter school movement — could be controversial among the Democratic voters he needs to convert.

Bloomberg’s presidential campaign is taking the unorthodox strategy of skipping early states like Iowa and New Hampshire completely, and investing in a massive campaign operation in California and other Super Tuesday states, and buying millions of dollars in TV ads here.

It won’t be his first experience with wildly expensive campaigns in the state. His biggest spending in California over the years came on the fight for taxes to combat the adverse health impacts of sugary drinks. Bloomberg spent a total of $19 million on two successful 2016 ballot measure campaigns in Oakland and San Francisco that raised taxes one penny per ounce on sugar-sweetened beverages, as well as $647,000 on a similar 2014 measure in Berkeley, according to data from the Secretary of State’s office.

It’s a pet issue for Bloomberg, who unsuccessfully tried to ban the sale of large sodas in New York before his plan was thrown out by a court.

In a similar vein, Bloomberg also spent a total of about $10 million on state and local propositions to increase cigarette taxes, ban flavored tobacco products, and preserve a San Francisco ban on e-cigarette sales, with a mixed record of success. As mayor, he banned smoking in New York’s bars, restaurants, parks and beaches.

The former mayor didn’t just give money to the California public health propositions — his New York team of political strategists helped plot strategy and was on the phone with the campaign team “almost daily,” said Larry Tramutola, an Oakland political consultant who led the Bay Area soda tax and flavored cigarette proposition fights.

Bloomberg’s brain trust went as far as to independently fact-check every detail in the campaign’s ads — a rare level of involvement by big political donors.

“They aren’t into writing a check and walking away,” Tramutola said.

The Oakland and San Francisco proposition campaigns likely would have lost without Bloomberg’s financial support, he said.

“The soda industry and the tobacco industry seemingly have unlimited dollars, and the amount of money the opposition was throwing in was so overwhelming,” Tramutola said. Bloomberg “helped balance the battle. Even though we were on the right side of the issue, we would not have been competitive without him.”

Another big chunk of Bloomberg’s money went to charter school movement. He gave more than $2 million to the California Charter Schools Association Advocates, which supports political candidates who back charter schools, and $3.5 million to a PAC set up by the organization to support former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s 2018 bid for governor.

He also gave $528,000 to the 2014 and 2018 campaigns of Marshall Tuck, a former charter school executive who ran unsuccessfully for state superintendent of public education, and to a group supporting Tuck.

That spending also dovetailed with Bloomberg’s agenda in New York, where he championed charter schools, allowing privately-run charters to use public school buildings.

“His name brought a lot of credibility to what we’re doing to help families,” said Gregory McGinity, the executive director of CCSA Advocates. “It’s very much an extension of the work he began in New York City.”

Bloomberg even got involved in individual school board races in Oakland, Los Angeles and San Mateo County, mostly bankrolling candidates who were considered supporters of charter schools.

Not all of Bloomberg’s political beneficiaries are fans of the former New York City mayor. Roseann Torres was baffled when a $700 check from one of the richest men in the world showed up in her mailbox during her first campaign for Oakland school board in 2012. She had never run for office before, and felt like the donations from Bloomberg and other wealthy charter school supporters around the country were an attempt to sway her to their ideology.

“I was like, why do billionaires in Manhattan care about schools in Oakland?” she remembered. “I was asking my husband, ‘What do I do with this check? Is this real?’”

After she was elected, Torres said she had a “falling-out” with pro-charter groups over her opposition to expanding charters in the city. Four years later, she found herself on the other side of Bloomberg’s money: GO Public Schools, an Oakland-based nonprofit that supports charters, spent $43,000 in an unsuccessful campaign to unseat her, bankrolled in part by a $300,000 donation from the former mayor.

“Now, I regret cashing that check,” Torres said.

In addition to schools and public health, Bloomberg supported various California candidates and propositions. He sent Arnold Schwarzenegger $44,600 during his 2006 re-election and later threw in $250,000 for his independent redistricting commission ballot measure.

He also pitched in for then-San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom’s bid for lieutenant governor in 2010 and gave $13,600 to his 2018 governor’s campaign (after earlier spending millions on the group supporting Newsom’s more moderate rival Villaraigosa). Newsom and other down-ballot candidates got more financial support from Everytown for Gun Safety, a gun-control group Bloomberg started and provided most of the funding for.

Bloomberg’s influence in California political circles goes beyond his campaign donations. His nonprofit, Bloomberg Philanthropies, has showered cities around the state with grants and sent some mayors to a training program at Harvard University. The beneficiaries include San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo and Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs, who were the first major California elected officials to endorse him

While some of his political history in the state could be controversial among Democrats, Bloomberg’s fans say that it’s unlikely to turn off anyone who might vote for him.

“Anybody who’s not going to vote for Bloomberg because of some of his past donations,” Schnur said, “probably wasn’t going to support him on the issues to begin with.”