Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans are continuing to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 4,708 U.S. adults in June 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.

As the number of coronavirus cases surges in many states across the United States, Republicans and Democrats increasingly view the disease in starkly different ways, from the personal health risks arising from the coronavirus outbreak to their comfort in engaging in everyday activities.

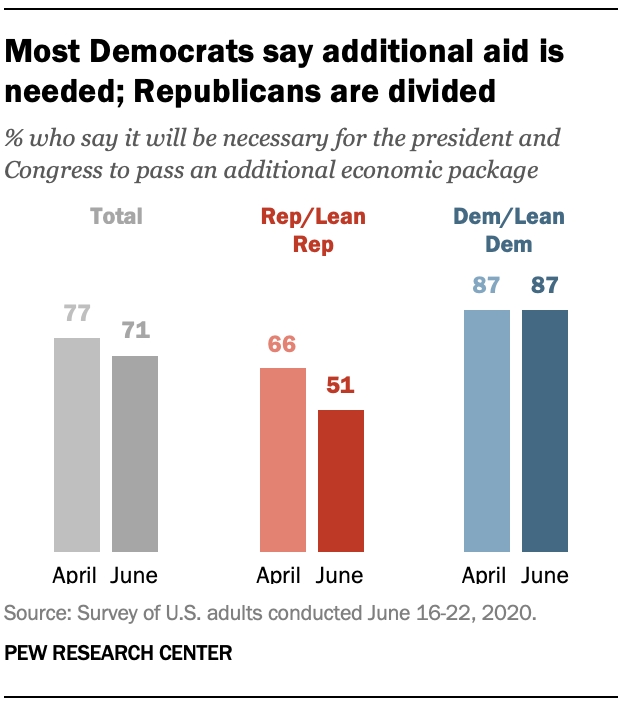

These differences extend to opinions about whether a new stimulus package will be needed to address the economic fallout from the coronavirus. Republicans are now much less likely to say an additional stimulus package is necessary than they were in early April, while Democrats continue to overwhelmingly say more economic assistance is needed.

These differences extend to opinions about whether a new stimulus package will be needed to address the economic fallout from the coronavirus. Republicans are now much less likely to say an additional stimulus package is necessary than they were in early April, while Democrats continue to overwhelmingly say more economic assistance is needed.

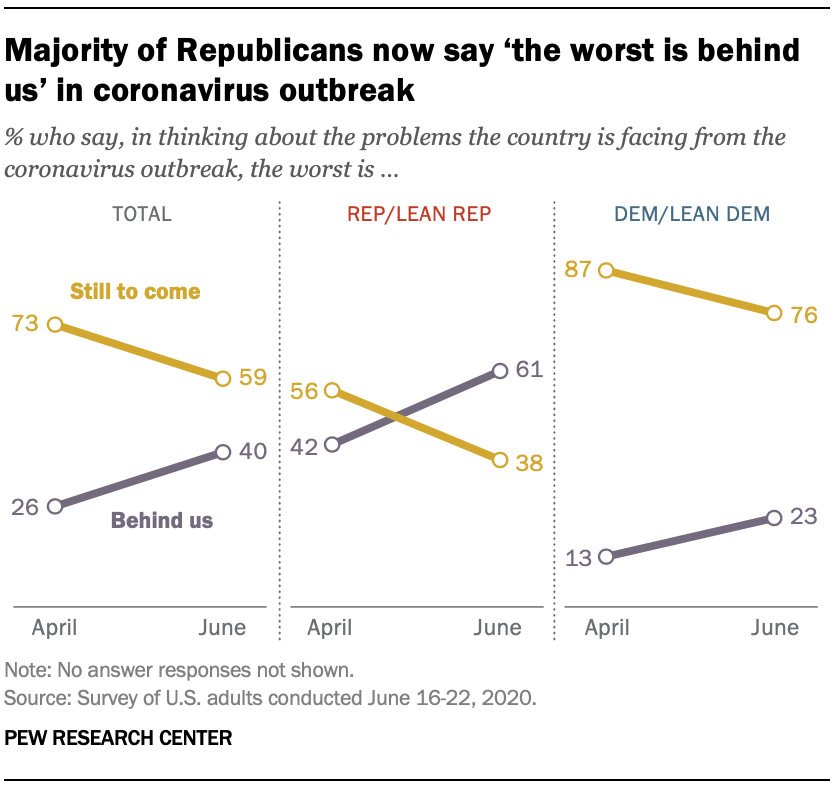

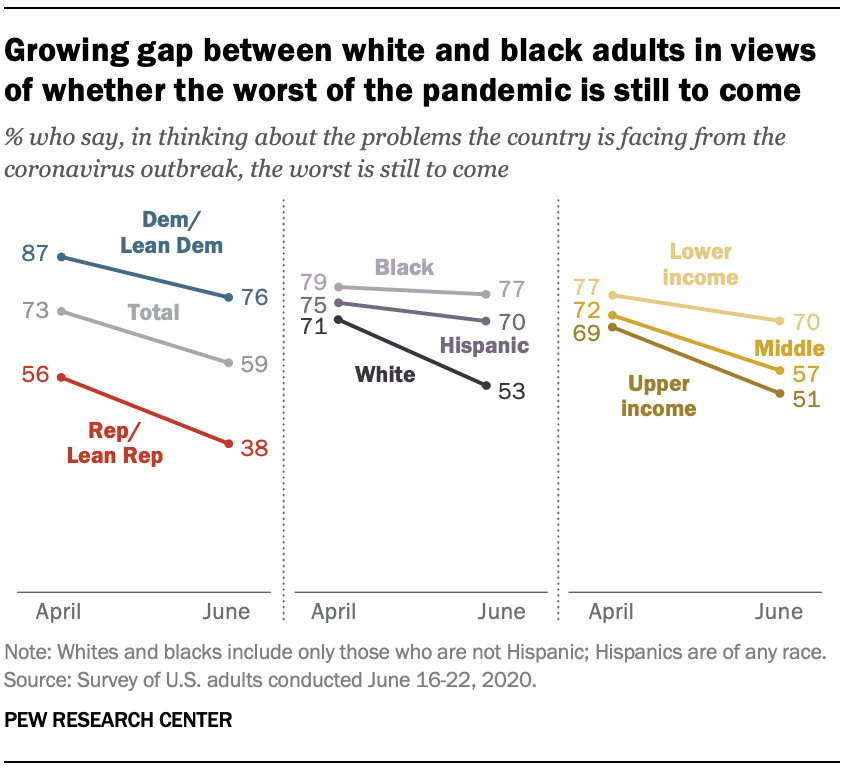

A growing share of Republicans believe that the nation has turned a corner in its struggle with the coronavirus. A majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (61%) now say that when thinking about the problems facing the country from the coronavirus, “the worst is behind us,” while 38% say the “worst is still to come.” This marks a reversal of opinion since early April, when a majority of Republicans (56%) said the worst was still to come.

By contrast, just 23% of Democrats and Democratic leaners say that the worst is behind us when it comes to problems from the coronavirus; more than three times as many Democrats (76%) say the worst is still to come. This is a more modest change from April, when an even larger majority of Democrats (87%) said the worst was still to come.

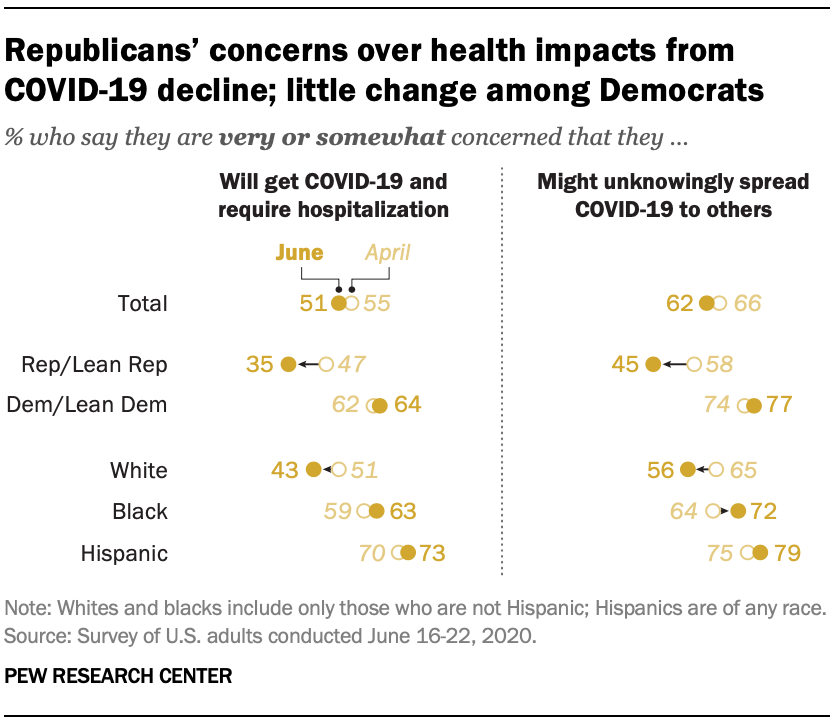

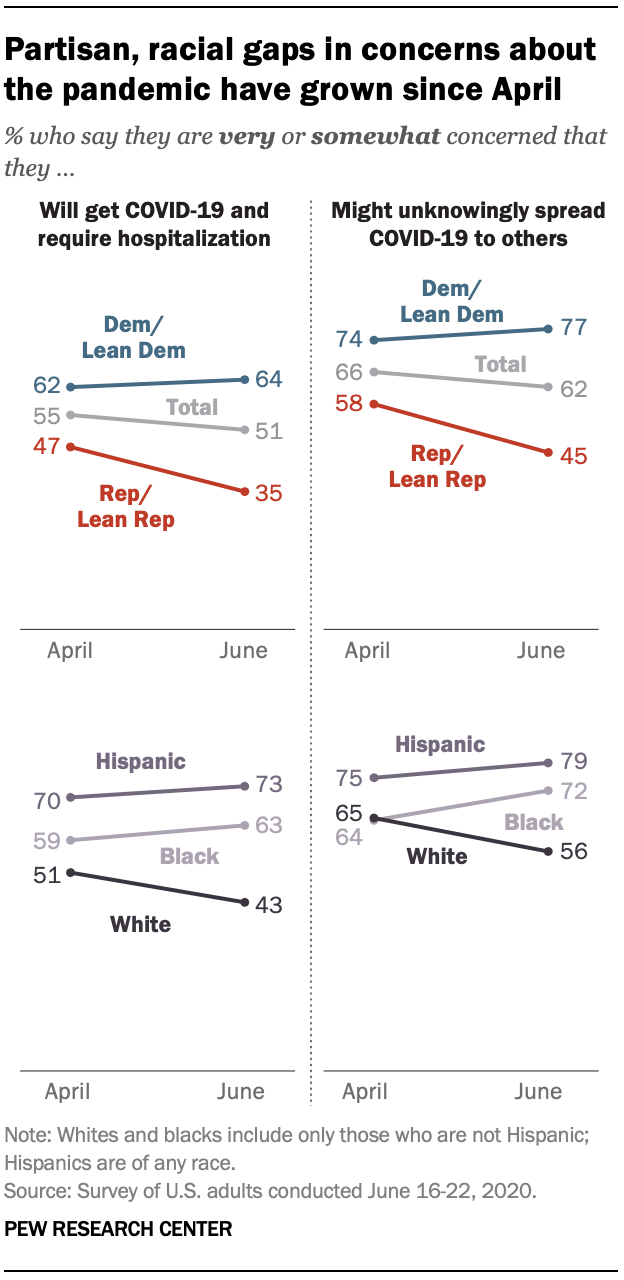

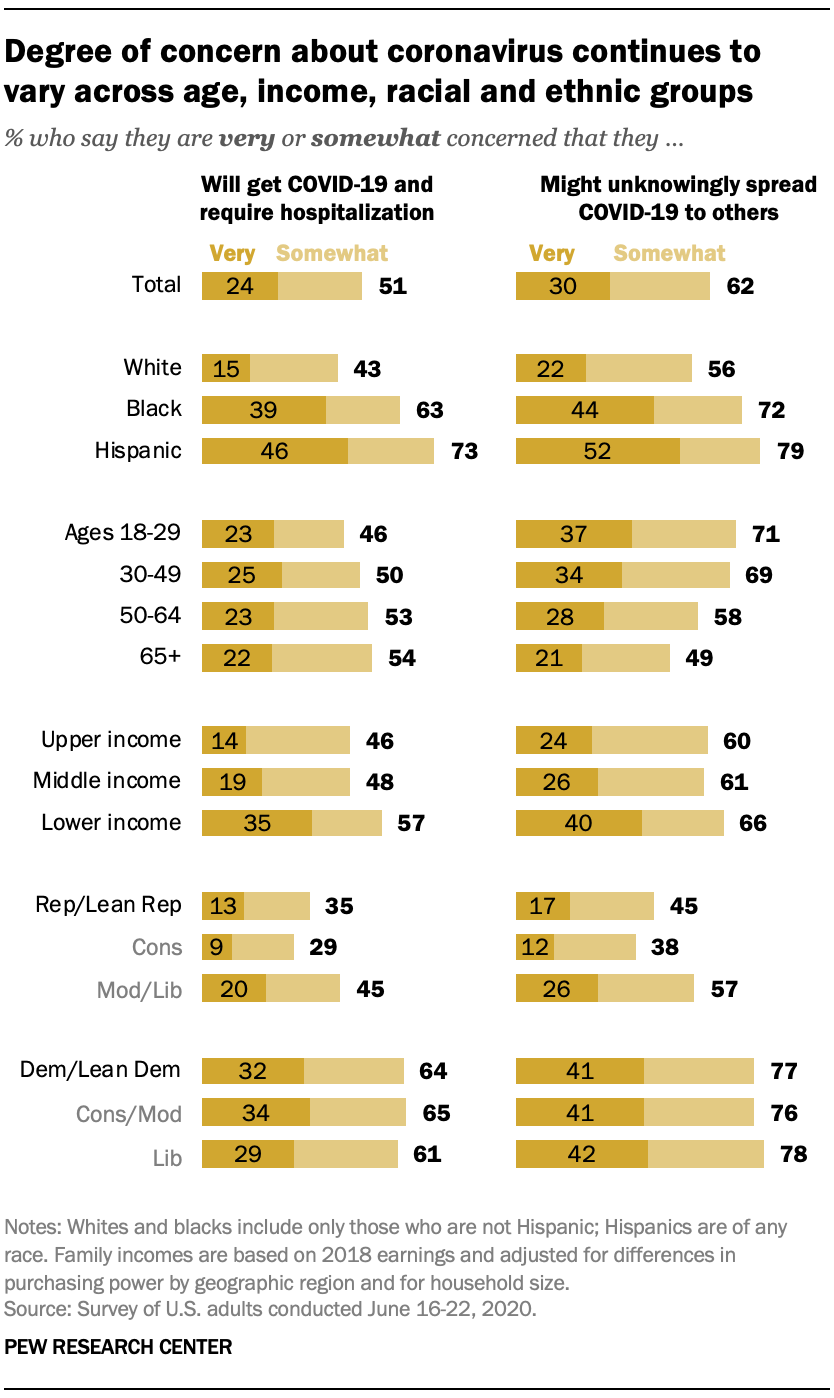

Among the public overall, health concerns from the coronavirus have changed little over the past two months: 62% are very or somewhat concerned they might unknowingly spread the coronavirus to others, including 30% who are very concerned about this, while 51% are concerned that they will get the coronavirus and require hospitalization (24% are very concerned).

Yet the partisan divide – as well as the racial and ethnic differences – in concerns about unknowingly spreading COVID-19 or contracting a serious case of the disease have widened. Today, fewer than half of Republicans (45%) are very or somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus, and only about a third (35%) worry they will contract COVID-19 and need to be hospitalized. In early April, a 58% majority of Republicans said they were concerned they may spread the disease without knowing it, and nearly half (47%) were concerned they would get a serious case of COVID-19.

Yet the partisan divide – as well as the racial and ethnic differences – in concerns about unknowingly spreading COVID-19 or contracting a serious case of the disease have widened. Today, fewer than half of Republicans (45%) are very or somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus, and only about a third (35%) worry they will contract COVID-19 and need to be hospitalized. In early April, a 58% majority of Republicans said they were concerned they may spread the disease without knowing it, and nearly half (47%) were concerned they would get a serious case of COVID-19.

Over this period, health concerns among Democrats have changed very little: Currently, 77% of Democrats are very or somewhat concerned they might spread the coronavirus, while 64% are concerned they will get the disease and need to be hospitalized.

Notably, concerns over unknowingly spreading the coronavirus have increased 8 percentage points among black Americans (from 64% to 72%) since early April, while decreasing by about the same amount (from 65% to 56%) among white Americans.

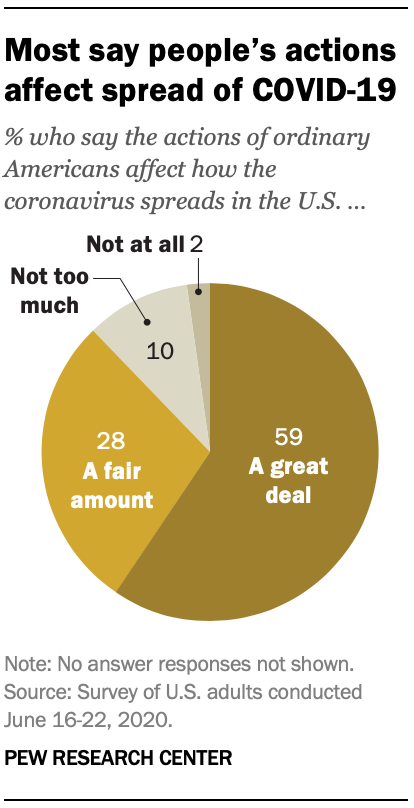

The new national survey by Pew Research Center, conducted June 16-22 among 4,708 adults using the Center’s American Trends Panel, finds that a sizable majority (87%) thinks that the actions of ordinary Americans have a great deal or fair amount of impact on how the coronavirus spreads in the U.S.

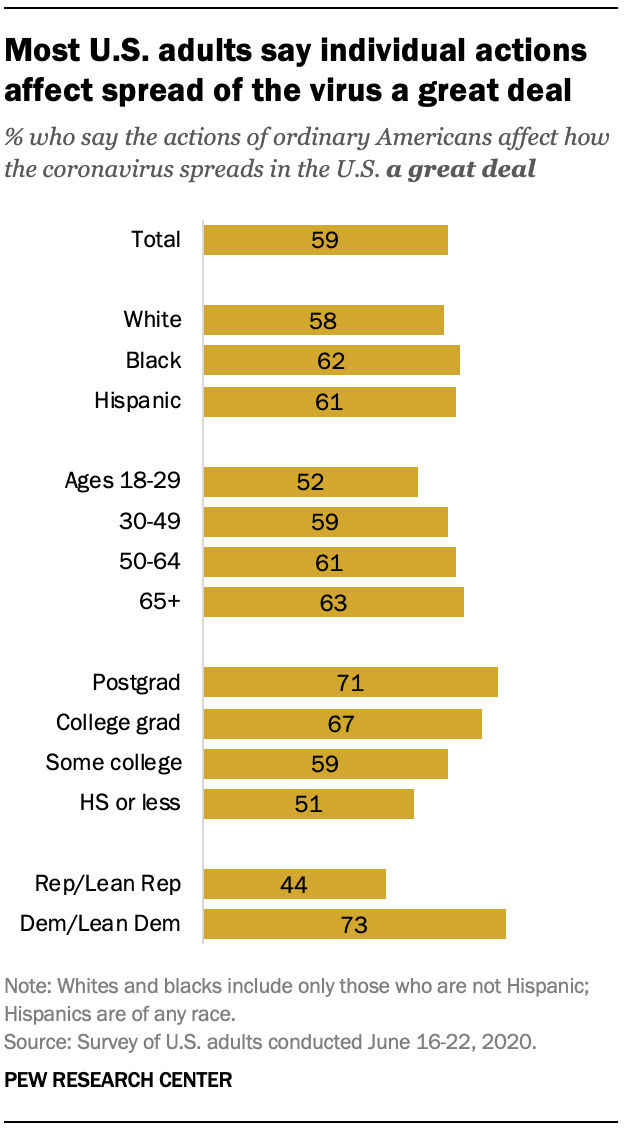

Nearly six-in-ten U.S. adults (59%) say ordinary Americans have a great deal of impact on the spread of the coronavirus, but while 73% of Democrats think the actions of ordinary people matter a great deal in affecting its spread, only 44% of Republicans say the same. These questions can be explored using the Center’s Pathways data tool.

Nearly six-in-ten U.S. adults (59%) say ordinary Americans have a great deal of impact on the spread of the coronavirus, but while 73% of Democrats think the actions of ordinary people matter a great deal in affecting its spread, only 44% of Republicans say the same. These questions can be explored using the Center’s Pathways data tool.

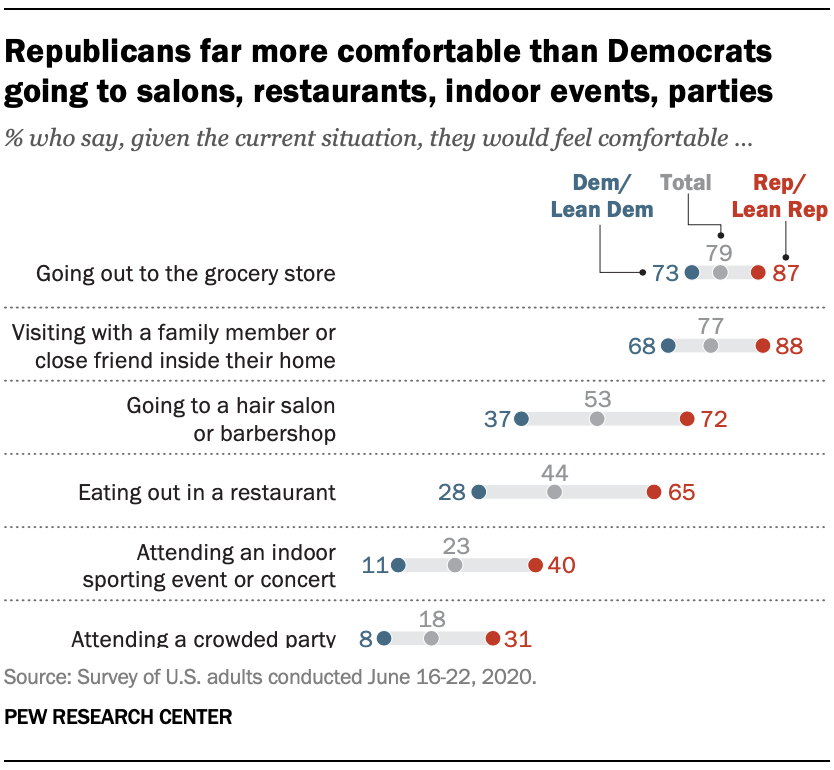

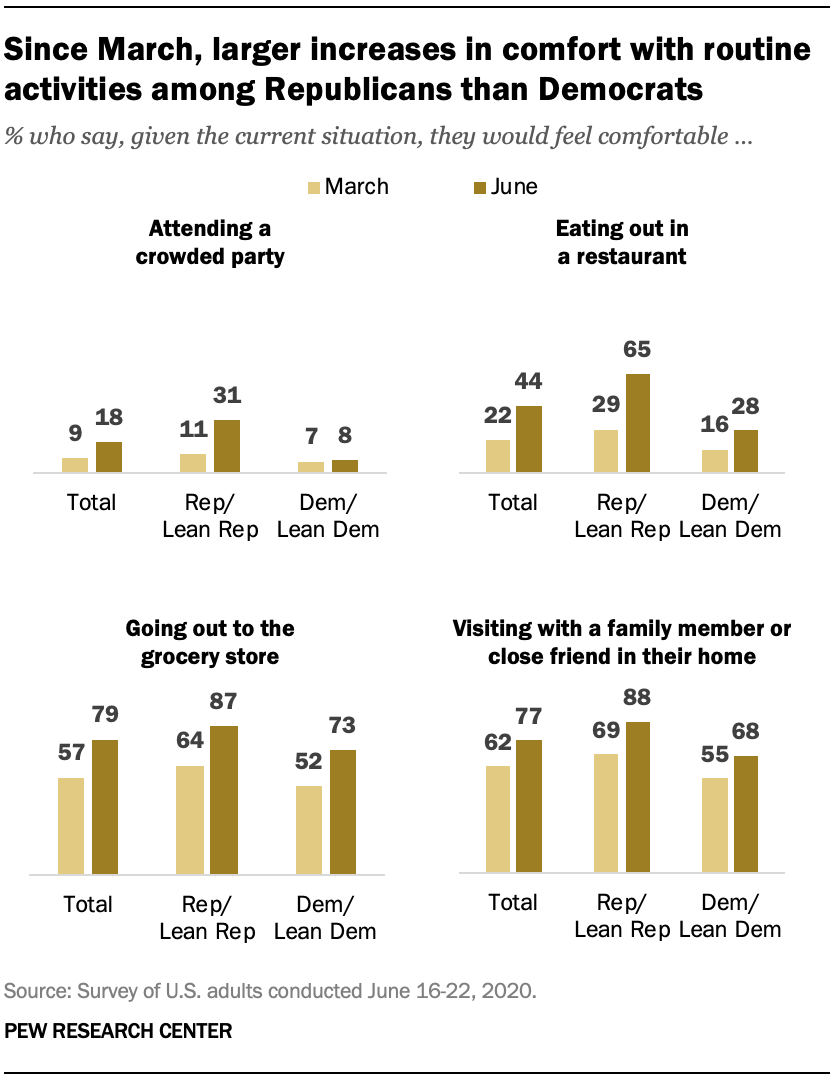

As more states and localities open their economies, Americans generally express much greater comfort undertaking routine daily activities than they did in mid-March, when the death toll from COVID-19 was surging. Twice as many people say they would be comfortable eating out in a restaurant (44%) than did so then (22%); 79% say they are comfortable going to a grocery store, up from 57% in March.

Yet the partisan differences in willingness to engage in such activities remain large – and in some cases have increased sharply. For example, Republicans are now nearly 40 percentage points more likely than Democrats to say they would be comfortable eating out in a restaurant (65% of Republicans vs. 28% of Democrats). In March, the gap was a more modest 13 points (29% of Republicans, 16% of Democrats).

The survey finds that the public’s assessments of the nation’s economy remain bleak. Just 25% rate economic conditions as excellent or good, little changed from April and far less positive than in January (57% excellent or good). Republicans are about five times as likely as Democrats to say the economy is doing well (46% vs. 9%).

The survey finds that the public’s assessments of the nation’s economy remain bleak. Just 25% rate economic conditions as excellent or good, little changed from April and far less positive than in January (57% excellent or good). Republicans are about five times as likely as Democrats to say the economy is doing well (46% vs. 9%).

While the public continues to say a new economic stimulus package is needed to address the impact of the coronavirus, Republicans have turned more skeptical about the need for additional economic stimulus. About seven-in-ten Americans (71%) say a new package is needed, beyond the $2 trillion package passed by President Donald Trump and Congress in March. That is down from 77% who said this in April.

Notably, the decrease has come entirely among Republicans, who are now divided over the need for more economic stimulus (51% say it will be necessary, 47% say it will not be needed). In April, two-thirds of Republicans (66%) said an additional stimulus would be needed. Democrats continue to be overwhelmingly supportive of additional economic stimulus (87% say it will be needed, unchanged from April).

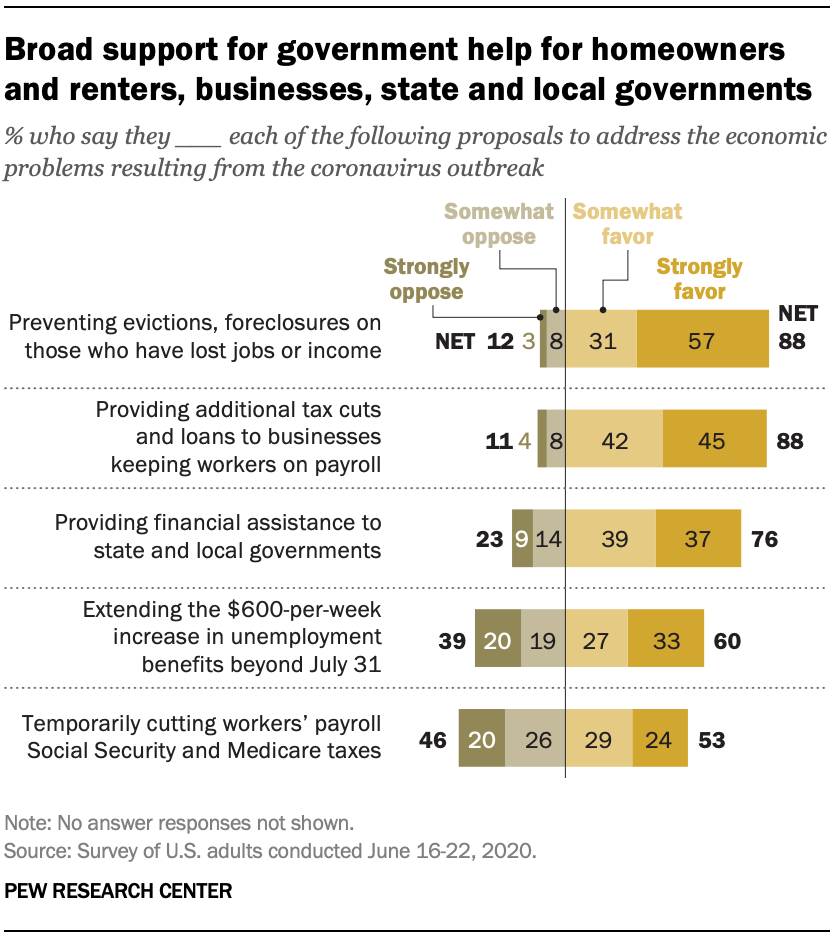

The public broadly supports proposals to help homeowners and renters and businesses address economic problems resulting from the coronavirus outbreak. Nearly nine-in-ten (88% each) – including large majorities in both parties – support aid for these groups.

The public broadly supports proposals to help homeowners and renters and businesses address economic problems resulting from the coronavirus outbreak. Nearly nine-in-ten (88% each) – including large majorities in both parties – support aid for these groups.

About three-quarters (76%) favor providing financial aid for state and local governments; however, while this proposal draws overwhelming support from Democrats (91% favor), a much smaller majority of Republicans (58%) favors it.

And while a majority of the public (60%) favors extending the $600 per week federal unemployment benefits beyond July 31, partisans are deeply divided. Nearly twice as many Democrats (77%) as Republicans (39%) support extending this unemployment aid.

A narrow majority of the public overall (53%), including comparable shares in both parties, supports a temporary cut in workers’ Social Security and Medicare taxes to address economic problems arising from the coronavirus outbreak.

Americans are generally comfortable grocery shopping and visiting family, more anxious about attending indoor events, crowded parties

As states have taken steps toward reopening, many Americans still express reservations about engaging in a variety of what had been seen as routine activities before the coronavirus outbreak. Only about one-in-five (18%) say that given the current situation with the coronavirus they would be comfortable attending a crowded party. A similar share (23%) say they would feel comfortable attending an indoor sporting event or concert.

As states have taken steps toward reopening, many Americans still express reservations about engaging in a variety of what had been seen as routine activities before the coronavirus outbreak. Only about one-in-five (18%) say that given the current situation with the coronavirus they would be comfortable attending a crowded party. A similar share (23%) say they would feel comfortable attending an indoor sporting event or concert.

A larger share, though fewer than half, say they would feel comfortable eating out in a restaurant (44%), while about half (53%) would feel comfortable going to a hair salon or barber shop. Sizable majorities of the public say they would be comfortable visiting with family or close friends in their homes (77%) and going to the grocery store (79%).

Across every item included in the survey, Republicans and Republican leaners express more comfort with engaging in these activities than do Democrats and Democratic leaners. The widest differences are on eating out in a restaurant, going to a hair salon or barbershop and attending an indoor sporting event or concert.

And while relatively few Americans say they would feel comfortable attending a crowded party, nearly four times as many Republicans (31%) as Democrats (8%) say they would feel comfortable doing this.

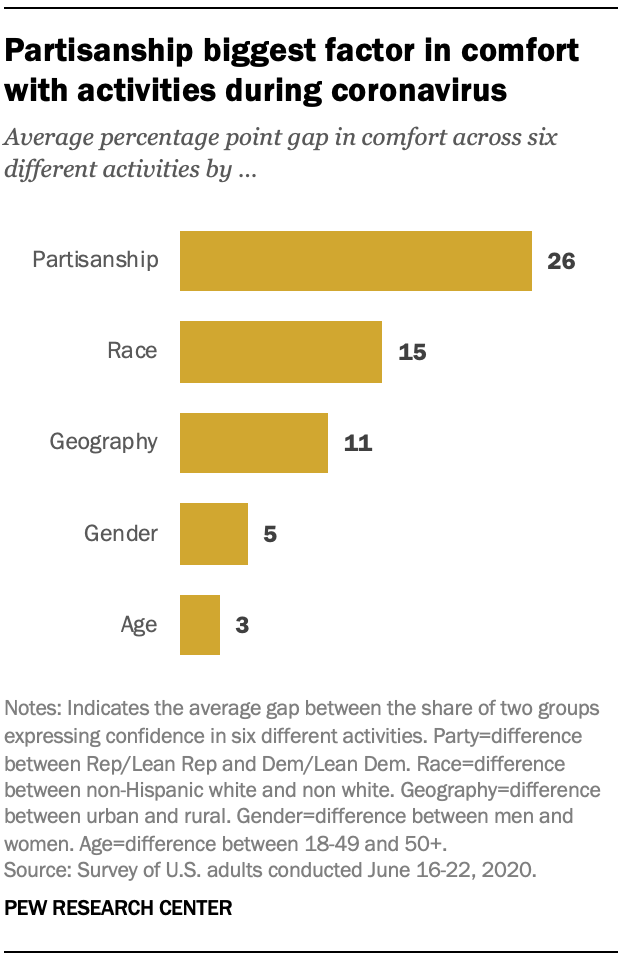

In every case, the differences between Republicans’ and Democrats’ levels of comfort far exceeds other demographic and even geographic differences. Across all six items, the average partisan gap in levels of comfort is nearly twice as big as the gap between whites and nonwhites and is far larger than the gap between men and women, those living in urban and rural communities, and the gap between younger and older Americans.

In every case, the differences between Republicans’ and Democrats’ levels of comfort far exceeds other demographic and even geographic differences. Across all six items, the average partisan gap in levels of comfort is nearly twice as big as the gap between whites and nonwhites and is far larger than the gap between men and women, those living in urban and rural communities, and the gap between younger and older Americans.

Americans’ level of comfort with each of these activities has risen across the board since the middle of March, when many states began to implement stay-at-home orders and other measures to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

However, the increases have been far more pronounced among Republicans than Democrats. For example, the shares of Republicans who express comfort with eating out in a restaurant and attending a crowded party have risen by 36 points and 20 points, respectively. Among Democrats, the share saying they would be comfortable eating in a restaurant has increased 12 points, and there has been no change in Democrats’ comfort with going to a crowded party.

However, the increases have been far more pronounced among Republicans than Democrats. For example, the shares of Republicans who express comfort with eating out in a restaurant and attending a crowded party have risen by 36 points and 20 points, respectively. Among Democrats, the share saying they would be comfortable eating in a restaurant has increased 12 points, and there has been no change in Democrats’ comfort with going to a crowded party.

Among both Democrats and Republicans, there have been significant increases since March in the shares saying they would be comfortable going to the grocery store and visiting with family and friends at their homes. Still, Republicans remain more likely than Democrats to say they would be comfortable engaging in these activities.

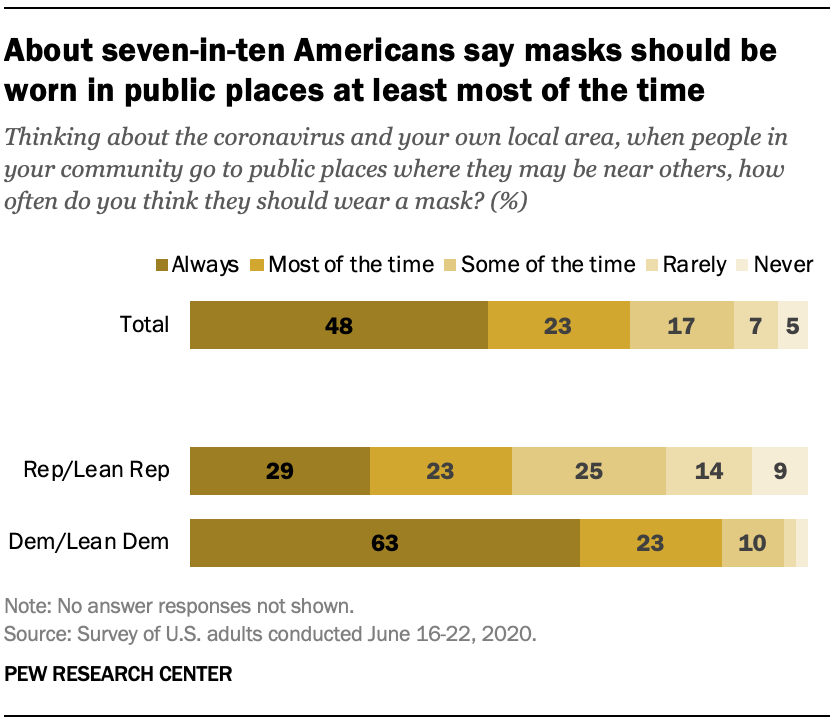

About seven-in-ten Americans (71%) say that people who go to public places in their communities where they may be near others should wear masks most of the time or always. An additional 17% say that masks should be worn “some of the time” in these situations and 12% say they should rarely or never be worn.

About seven-in-ten Americans (71%) say that people who go to public places in their communities where they may be near others should wear masks most of the time or always. An additional 17% say that masks should be worn “some of the time” in these situations and 12% say they should rarely or never be worn.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are about twice as likely as Republicans and Republican leaners to say that masks should be worn always (63% vs. 29%). Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say that masks should rarely or never be worn (23% vs. 4%).

Republicans also are less likely than Democrats to say they have worn masks in stores or other businesses always or most of the time in the past month. For more, see “Most Americans say they regularly wore a mask in the past month; fewer see others doing it.”

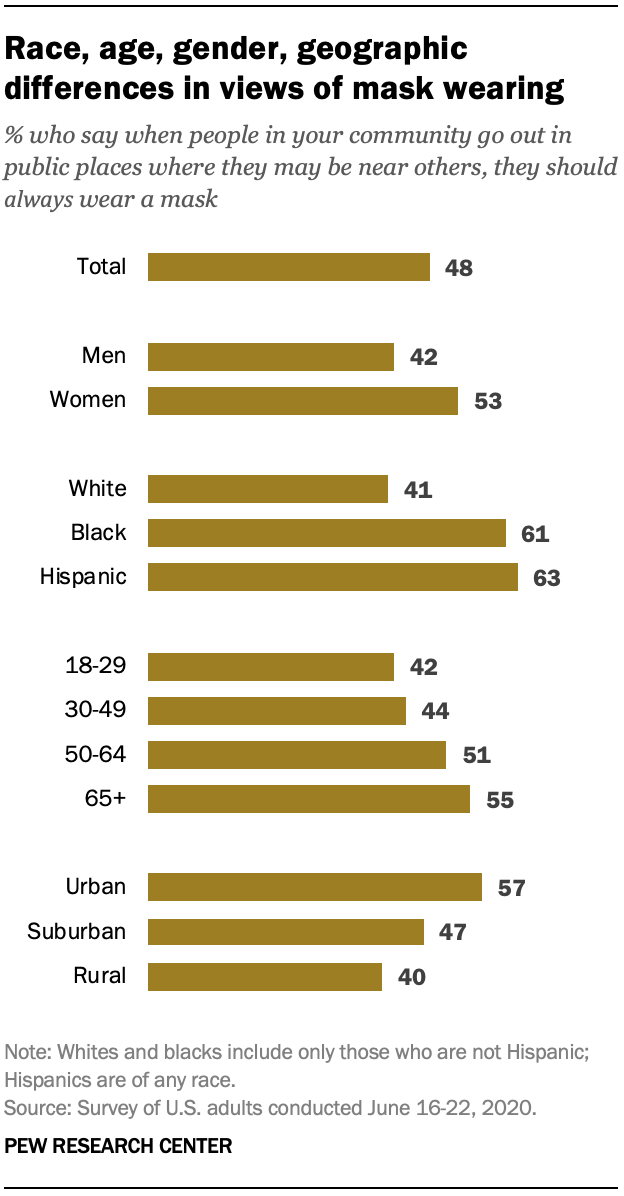

Beyond partisan differences in attitudes about mask wearing, there are substantial gender, racial, age and geographic differences.

Beyond partisan differences in attitudes about mask wearing, there are substantial gender, racial, age and geographic differences.

Women are more likely than men to say that masks should always be worn in public places (53% vs. 42%). White people are substantially less likely than black and Hispanic adults to say that masks should always be worn.

Age is also strongly related to views about mask wearing. About four-in-ten (42%) of those ages 18 to 29 say that masks should always be worn, compared with 55% of those 65 and older.

A majority of people living in urban areas (57%) say people who go out in public places should always wear masks, compared with 47% of suburban residents and 40% of those who live in rural areas.

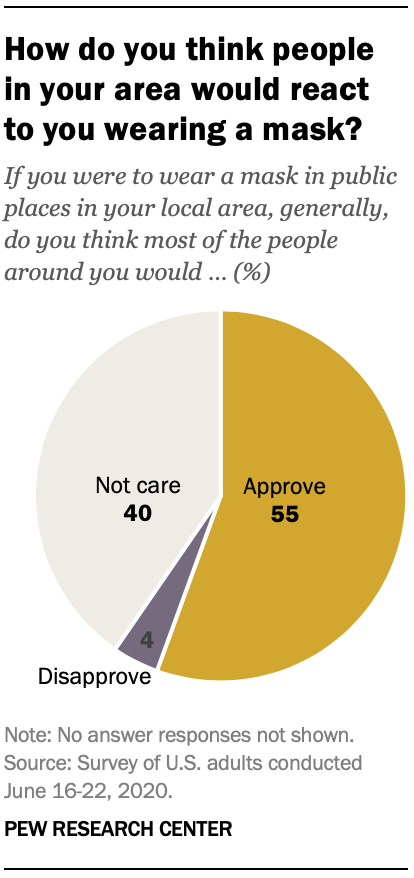

Few think they would face criticism for wearing a mask in public

A majority of Americans (55%) say that, if they were to wear a mask in their local area, people around them would generally approve; only 4% think that people in their communities would disapprove, while 40% say that people would not care one way or the other.

A majority of Americans (55%) say that, if they were to wear a mask in their local area, people around them would generally approve; only 4% think that people in their communities would disapprove, while 40% say that people would not care one way or the other.

Compared with views about when masks should be worn, there are much smaller gaps in perceptions of others’ views about the practice. Democrats are more likely than Republicans to believe that others in their communities would approve of mask-wearing (62% of Democrats say this compared with 48% of Republicans), but Republicans are not substantially more likely than Democrats to say that other people in their communities would disapprove of mask-wearing (48% of Republicans and 33% of Democrats say that most people in their area would not care one way or the other).

Nearly six-in-ten adults (59%) say that the actions of ordinary Americans have a great deal of impact on how the coronavirus spreads through the country, while 28% say that individual actions affect the spread of the virus a fair amount; about one-in-ten (12%) say that the actions of ordinary Americans affect the spread of the virus either not too much (10%) or not at all (2%).

Nearly three-quarters of Democrats (73%) say that the actions of ordinary Americans affect how the coronavirus spreads in the U.S. a great deal and 22% say the actions of ordinary Americans have a fair amount of effect. Just 5% of Democrats say that individual actions affect how the virus spreads either not too much or not at all.

Nearly three-quarters of Democrats (73%) say that the actions of ordinary Americans affect how the coronavirus spreads in the U.S. a great deal and 22% say the actions of ordinary Americans have a fair amount of effect. Just 5% of Democrats say that individual actions affect how the virus spreads either not too much or not at all.

While most Republicans say that individual actions affect the spread of the coronavirus, fewer than half (44%) say that this affects the spread of the virus a great deal. About one-third (35%) say that individual actions affect how the virus spreads a fair amount, and roughly two-in-ten Republicans (21%) say that individual actions affect how the coronavirus spreads either not too much or not at all.

There are also notable age and educational differences in beliefs about the impact of individual actions. About half (52%) of adults ages 18 to 29 say that the actions of ordinary people affect the spread of the virus a great deal, compared with more than six-in-ten (63%) of those 65 and older. And those with a postgraduate degree are 20 percentage points more likely to say this than adults without any college experience.

Since April, the proportion of adults saying they are very or somewhat concerned that they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization has fallen slightly, from 55% to 51%. The proportion saying they are very or somewhat concerned that they might unknowingly spread COVID-19 to others has similarly dropped modestly, from 66% to 62%.

Since April, the proportion of adults saying they are very or somewhat concerned that they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization has fallen slightly, from 55% to 51%. The proportion saying they are very or somewhat concerned that they might unknowingly spread COVID-19 to others has similarly dropped modestly, from 66% to 62%.

Partisans’ concerns about the coronavirus have diverged over the past two months. Among Republicans, concerns about catching and spreading the virus have both decreased substantially: 35% of Republicans now say they are very or somewhat concerned they will be hospitalized due to COVID-19, down from 47% in April. And while a 58% majority of Republicans said they were very or somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the virus in April, fewer than half (45%) now say they are very or somewhat concerned about this.

Among Democrats, concerns about catching and spreading the virus are relatively unchanged since April. About six-in-ten Democrats (64%) continue to say they are very or somewhat concerned that they will require hospitalization due to the virus, while about three-quarters (77%) are very or somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading it.

The gaps between white adults’ concerns about getting or spreading the coronavirus and Hispanic and black adults’ concerns also have grown since April, as the concerns of white adults have declined while those of black and Hispanic adults have not.

The gaps between white adults’ concerns about getting or spreading the coronavirus and Hispanic and black adults’ concerns also have grown since April, as the concerns of white adults have declined while those of black and Hispanic adults have not.

Today, clear majorities of black (63%) and Hispanic (73%) adults say they are very or somewhat concerned about getting COVID-19 and requiring hospitalization, which is little different than the shares saying this in April. By comparison, 43% of white adults now say this (down from 51% in April).

There is a similar pattern in levels of concern about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus. Today, 79% of Hispanic adults and 72% of black adults say they are at least somewhat concerned they might unknowingly spread the coronavirus, while 56% of white adults say this. The share of white adults saying this has dropped since April, while concerns among blacks and Hispanics are as high or higher than they were two months ago.

Among Democrats, whites (75%) and blacks (76%) express similar levels of concern they could unknowingly spread the coronavirus. Hispanic Democrats are slightly more likely to say they are very or somewhat concerned about this (85%). By comparison, 42% of white Republicans say they are at least somewhat concerned they could unknowingly spread the coronavirus.

However, black Democrats (67%) and Hispanic Democrats (76%) are more likely than white Democrats (58%) to say they are very or somewhat concerned they might require hospitalization due to COVID-19. Still, the partisan differences on this question are greater than the racial and ethnic differences (31% of white Republicans vs. 67% of white Democrats are concerned they may need to be hospitalized from getting COVID-19).

Older adults have become less concerned about both catching and spreading COVID-19 since April: 54% of adults ages 65 and older are very or somewhat concerned about requiring hospitalization due to COVID-19, down from 62% two months ago. The proportion expressing concern about unknowingly spreading the virus fell by a similar amount, to 49% from 57%. Meanwhile, adults ages 18 to 29 have become slightly more concerned about getting COVID-19 and requiring hospitalization (39% very or somewhat concerned in April vs. 46% in June). Concerns about unknowingly spreading the virus among this group have not changed during this period.

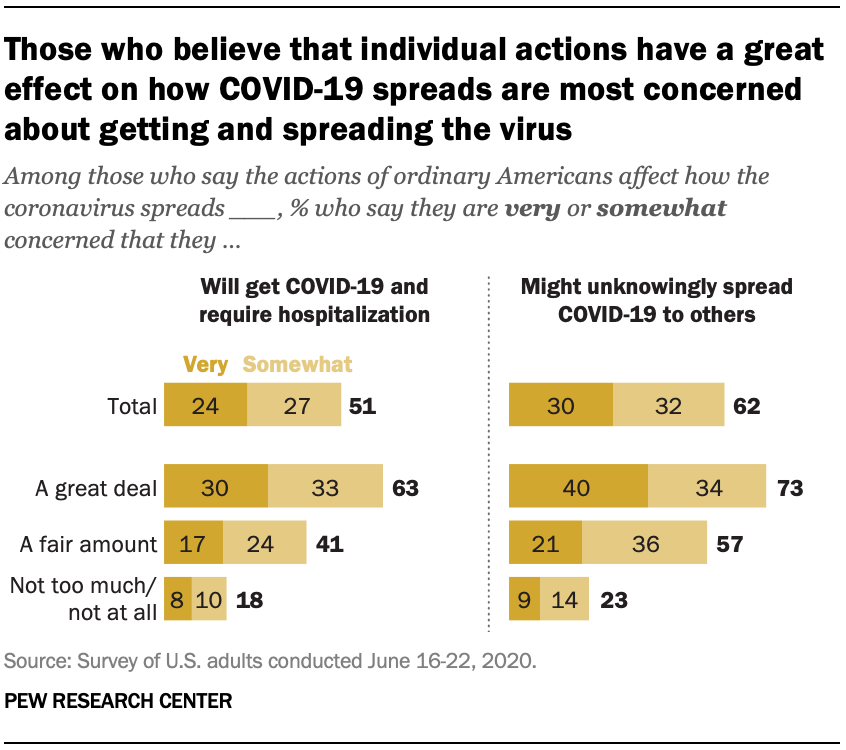

Those who say the actions of ordinary Americans affect how the coronavirus spreads a great deal are the most likely to express concerns about getting COVID-19 and requiring hospitalization or about unknowingly spreading the virus to others.

Those who say the actions of ordinary Americans affect how the coronavirus spreads a great deal are the most likely to express concerns about getting COVID-19 and requiring hospitalization or about unknowingly spreading the virus to others.

Among the nearly six-in-ten adults who say that individual actions have “a great deal” of impact, 63% are at least somewhat concerned they will require hospitalization due to COVID-19. By comparison, among the 28% who say that individual actions have “a fair amount” of impact on the spread of the virus, 41% are very or somewhat concerned that they will require hospitalization. Just 18% of the small share of adults who say that the actions of ordinary Americans have little or no effect on how the coronavirus spreads in the U.S. express concern about hospitalization resulting from COVID-19. There is a nearly identical pattern when it comes to concerns about unknowingly spreading the virus to others.

Members of both parties are more likely to say the worst has passed, but racial and ethnic divides have grown

Roughly six-in-ten Americans (59%) now say that the worst of the problems the country faces from the coronavirus outbreak are still to come, while 40% say the worst is behind us. Over the past two months, the share of adults saying the worst is still to come has fallen from 73% to 59%.

A majority of Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party (61%) now say that the worst has passed, while 38% say the worst is still to come. The share of Republicans saying the worst is still to come has decreased by nearly 20 percentage points since April.

A majority of Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party (61%) now say that the worst has passed, while 38% say the worst is still to come. The share of Republicans saying the worst is still to come has decreased by nearly 20 percentage points since April.

Democrats and Democratic leaners have also become somewhat less likely to say that the worst of the pandemic lies ahead, though about three-quarters (76%) continue to say this. In April, nearly nine-in-ten Democrats (87%) said the worst was still to come.

Despite members of both parties becoming less likely to say the worst is still to come, the steeper decline among Republicans means that the partisan gap on this question has increased, from about 30 points in April to nearly 40 points in June.

Views of the trajectory of the pandemic among members of different racial and ethnic groups have also diverged over the same period. In April, there were only modest racial and ethnic differences in expectations: 79% of black adults, 75% of Hispanic adults and 71% of white adults said that the worst of the crisis was still to come. Views among black Americans are essentially unchanged two months later, while the proportion of Hispanic Americans saying the worst is still to come has decreased slightly to 70%. Meanwhile, the share of whites saying the worst is still to come has decreased from 71% to 53%. The gap between white and black adults on this question has grown from 8 points to 24 points.

Additionally, individuals living in upper-income and middle-income households are now much more likely than those in lower-income households to say the worst of the pandemic is behind the country. About half of upper-income earners (51%) currently say that the worst is still to come, down from 69% in April. Similarly, the share of those in middle-income households who say the worst is still to come has decreased from 72% in April to 57%. Among those in lower-income households, the share saying the worst is still to come has declined much more modestly, from 77% to 70%.

Most Americans say additional COVID-19 financial aid will be needed

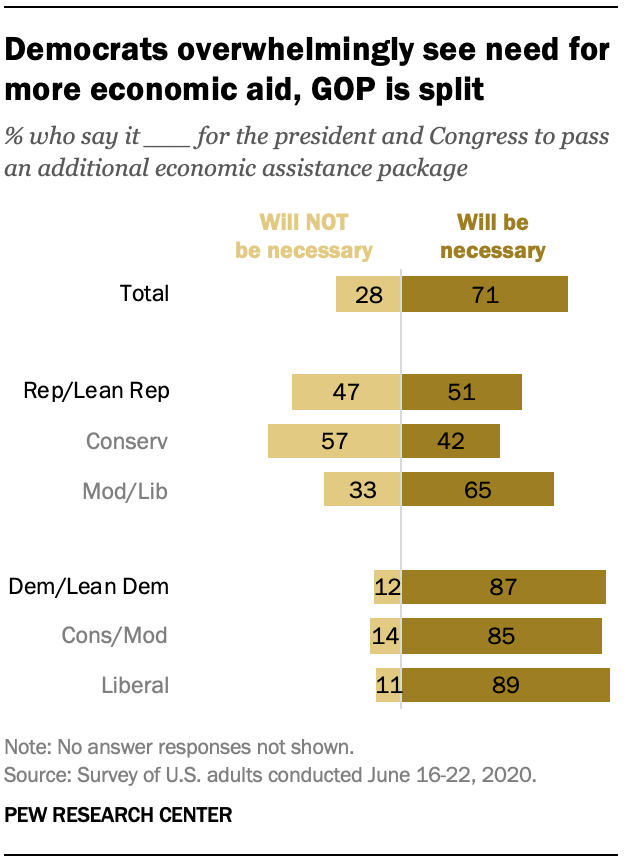

In April, there was broad bipartisan support for the $2 trillion federal coronavirus aid package. Today, a sizable majority of the public (71%) thinks it will be necessary for the president and Congress to pass an additional economic assistance package for the country, with support for a second package much higher among Democrats than Republicans.

In April, there was broad bipartisan support for the $2 trillion federal coronavirus aid package. Today, a sizable majority of the public (71%) thinks it will be necessary for the president and Congress to pass an additional economic assistance package for the country, with support for a second package much higher among Democrats than Republicans.

About nine-in-ten Democrats (87%) say it will be necessary to pass another economic assistance package. However, views among Republicans are divided: 51% say a new economic package will be necessary, while 47% say it will not be necessary.

There are ideological differences within the GOP about the need for additional aid: While a majority of conservative Republicans (57%) say that another economic assistance package will not be necessary, about two-thirds of moderate and liberal Republicans (65%) say there is a need for another financial aid bill.

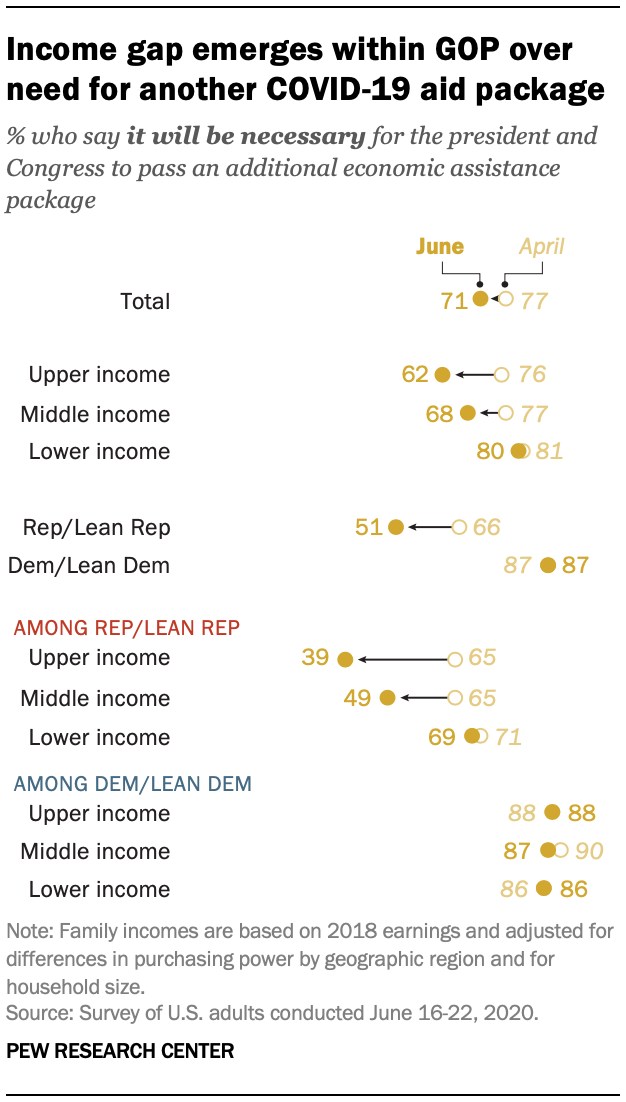

In April, the view that another financial aid package would be necessary was somewhat more widespread than it is today (77% said this then, 71% today).

Since April, views about the need for an additional financial package have declined among upper- and middle-income households. Today, 62% of upper-income Americans (down from 76% in April) and 68% of middle-income Americans (down from 77%) say there is a need for a second economic assistance package. By contrast, views among lower-income Americans are basically unchanged, with about eight-in-ten continuing to say that political leaders will need to pass another financial aid package.

Since April, views about the need for an additional financial package have declined among upper- and middle-income households. Today, 62% of upper-income Americans (down from 76% in April) and 68% of middle-income Americans (down from 77%) say there is a need for a second economic assistance package. By contrast, views among lower-income Americans are basically unchanged, with about eight-in-ten continuing to say that political leaders will need to pass another financial aid package.

The partisan gap in views of an additional economic package has also increased in the last two months. While the views of Democrats have are unchanged since April (87% say more aid is necessary), the share of Republicans who say an additional financial aid package is necessary has sharply declined from 66% who said this April to 51% who say this today.

Among Republicans, this decline has come almost entirely among those in the upper and middle income categories.

Among upper-income Republicans, the share saying an additional financial aid package is needed has declined from 65% in April to 39% today. In comparison, 69% of Republicans in lower-income households currently say an additional economic package will be necessary, nearly identical to the 71% who said this in April.

There are no differences by income among Democrats in assessments of the need for another economic aid package.

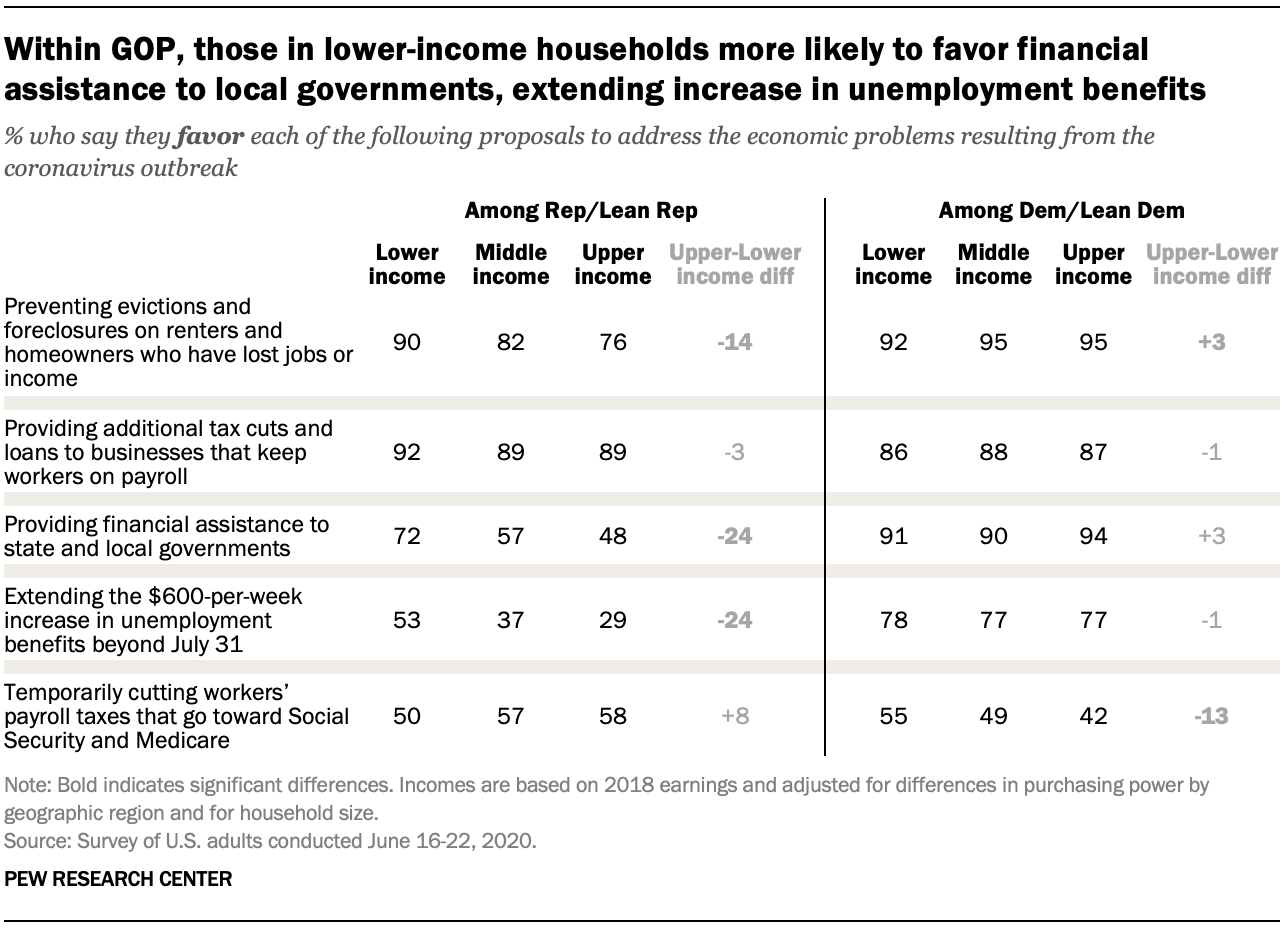

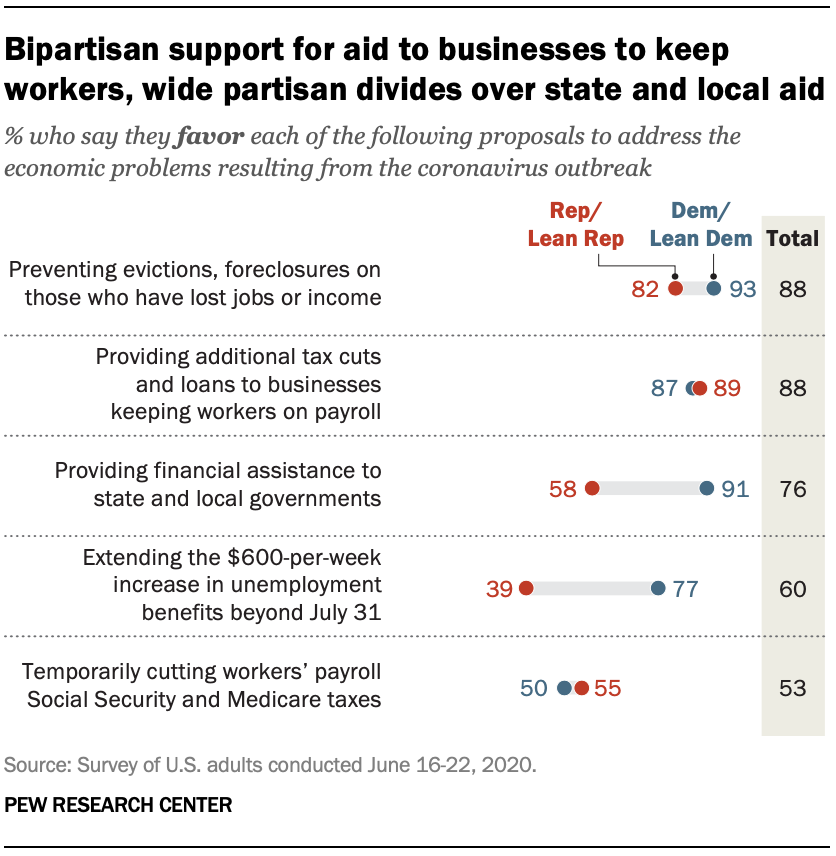

When it comes to proposals to address the economic problems resulting from the coronavirus outbreak, there are a few areas of broad bipartisan agreement, while other proposals draw more support from Democrats than Republicans.

Majorities of both Republicans (82%) and Democrats (93%) favor preventing evictions and foreclosure on renters and homeowners who have lost jobs or income, while roughly nine-in-ten in both parties (87% of Republicans, 89% of Democrats) favor providing additional tax cuts and loans to businesses that keep their workers on the payroll. However, a much larger share of Democrats (69%) than Republicans (42%) strongly favor preventing evictions and foreclosures.

Majorities of both Republicans (82%) and Democrats (93%) favor preventing evictions and foreclosure on renters and homeowners who have lost jobs or income, while roughly nine-in-ten in both parties (87% of Republicans, 89% of Democrats) favor providing additional tax cuts and loans to businesses that keep their workers on the payroll. However, a much larger share of Democrats (69%) than Republicans (42%) strongly favor preventing evictions and foreclosures.

There are wide partisan gaps on financial assistance to state and local governments affected by the coronavirus outbreak: While 91% of Democrats favor this proposal, a smaller majority (58%) of Republicans say the same. And although about three-quarters of Democrats (77%) favor extending the weekly $600 increase in unemployment benefits beyond the current July 31 expiration date, this is supported by just 39% of Republicans.

Within partisan groups, there are differences in views of these proposals by household income.

Among Republicans, those with lower household incomes are more likely to favor several proposals than Republicans in higher income tiers. For example, Republicans with lower household incomes (72%) are more likely than middle-income (57%) and upper-income Republicans (48%) to favor providing financial assistance to state and local governments. In addition, Republicans with lower family incomes (53%) are also more likely than middle-income (37%) and upper-income (29%) Republicans to favor extending the weekly $600 increase in unemployment benefits beyond the end of the July.

And although Democrats across income tiers are largely in agreement on many of the proposals asked in this survey, Democrats with lower household incomes (55%) are more likely than middle-income Democrats (49%) and upper-income Democrats (42%) to favor temporarily cutting workers’ payroll taxes that go toward Social Security and Medicare.

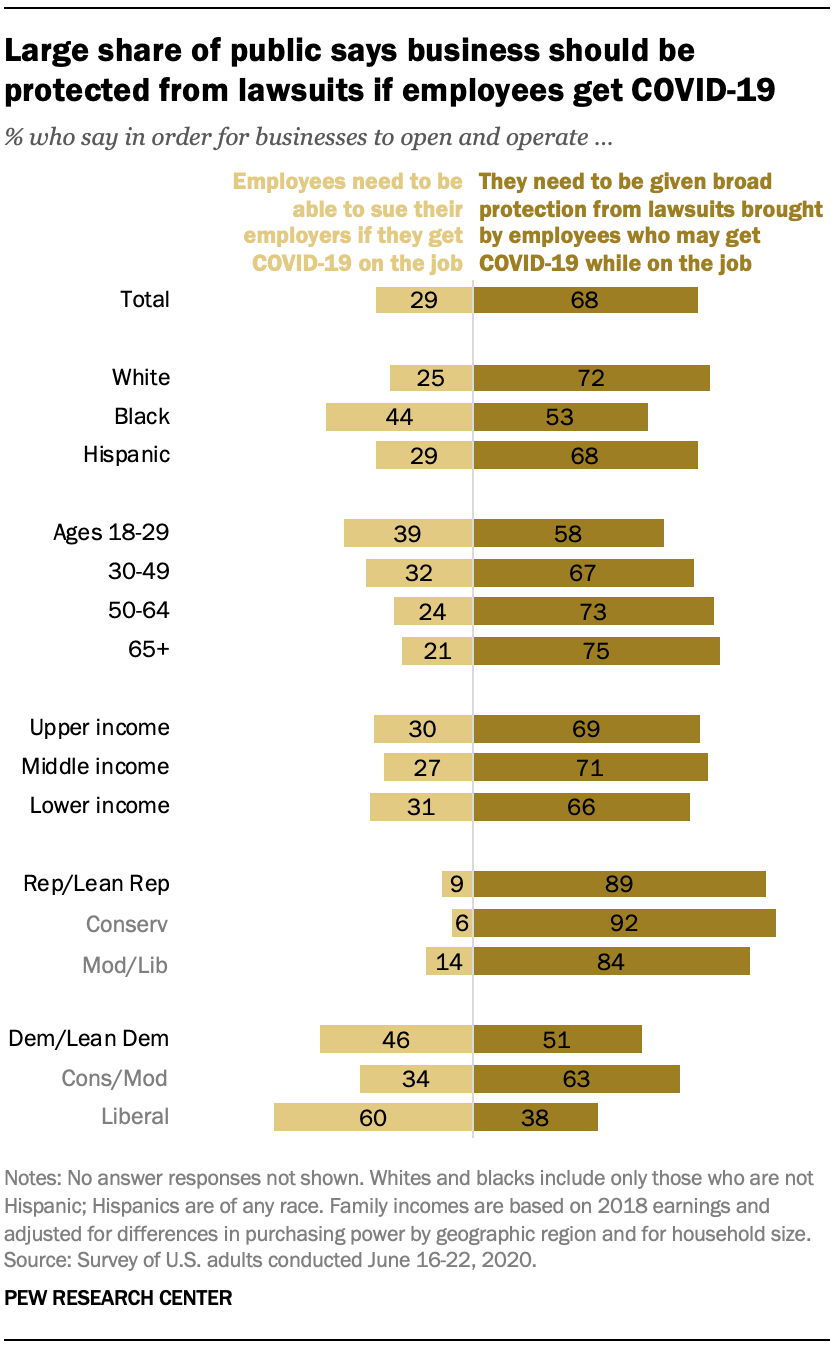

Most Americans say businesses should be protected from lawsuits if employees contract COVID-19 on the job

As states across the country are lifting stay-at-home orders and more businesses are increasingly reopening, there has been discussion about the extent to which employers should be held responsible if their employees get COVID-19 at work.

As states across the country are lifting stay-at-home orders and more businesses are increasingly reopening, there has been discussion about the extent to which employers should be held responsible if their employees get COVID-19 at work.

About seven-in-ten Americans (68%) say in order for businesses to open and operate, “businesses need to be given broad protection from lawsuits brought by employees who may get COVID-19 while working,” while 29% say “employees need to be able to sue their employers if they catch the coronavirus while on the job, even if it makes it harder for businesses to reopen.”

While majorities of Americans – across demographic groups – say that in order for business to open and operate, they need to be protected from being held liable if their employees get COVID-19, there are differences in views by race and ethnicity, age, and partisan affiliation.

Black adults (53%) are less likely than white (72%) and Hispanic (68%) adults to say that business should be given broad protections from lawsuits. About four-in-ten black adults (44%) say employees should be able to sue their employers if they contract COVID-19.

Older adults are more likely than younger adults to say businesses need broad protections from lawsuits: 75% of adults ages 65 and older say this, compared with 58% of adults ages 18 to 29.

There is near universal agreement among Republicans and Republican leaners that businesses should be protected against lawsuits from employees who contract the coronavirus at work: About nine-in-ten Republicans (89%) say business should be protected, while only 9% of Republicans say employees should have the right to sue if this happens.

Democrats are divided over who should have more legal protection if an employee contracts coronavirus while working: 51% say businesses should receive protection from lawsuits, while 46% say that employees should have the right to sue their employers if they get the coronavirus. And while a majority of conservative and moderate Democrats say business should have protections (63% say this), a 60% majority of liberal Democrats say employees should have the ability to sue.

Views of the national economy

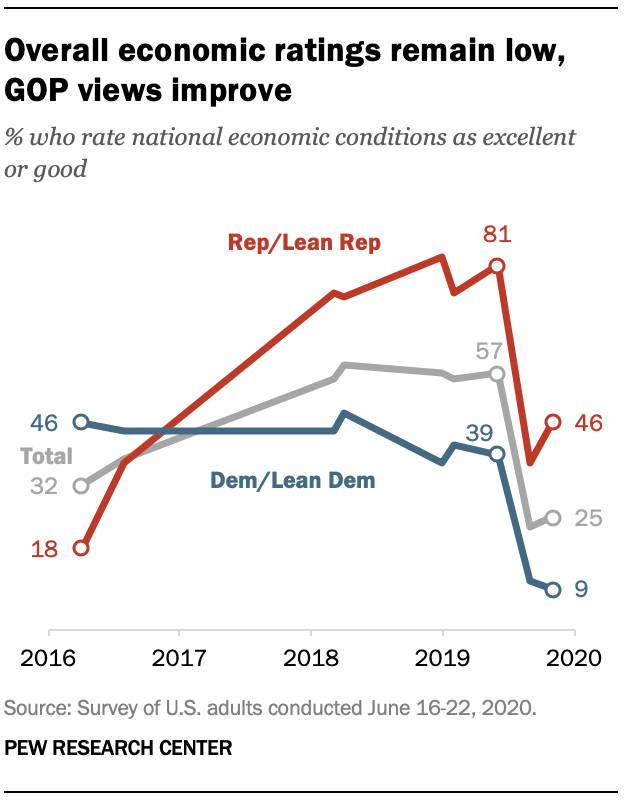

The public continues to hold negative views of the national economy. Currently, just a quarter of Americans rate national economic conditions as excellent or good, while 44% rate conditions as only fair and 30% say they are poor.

The share of the public holding positive views is similar to April, when 23% of Americans rated the economy as excellent or good, but remain significantly more negative than they were in January, prior to the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S., when 57% of Americans rated the economy as excellent or good.

The share of the public holding positive views is similar to April, when 23% of Americans rated the economy as excellent or good, but remain significantly more negative than they were in January, prior to the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S., when 57% of Americans rated the economy as excellent or good.

While overall views of the economy are little changed over the last two months, assessments of the economy have grown more positive among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents: 46% now rate the economy as excellent or good, up from 37% in April.

As was the case in April, only about one-in-ten (9%) Democrats and Democratic leaners currently rate the economy as excellent or good.

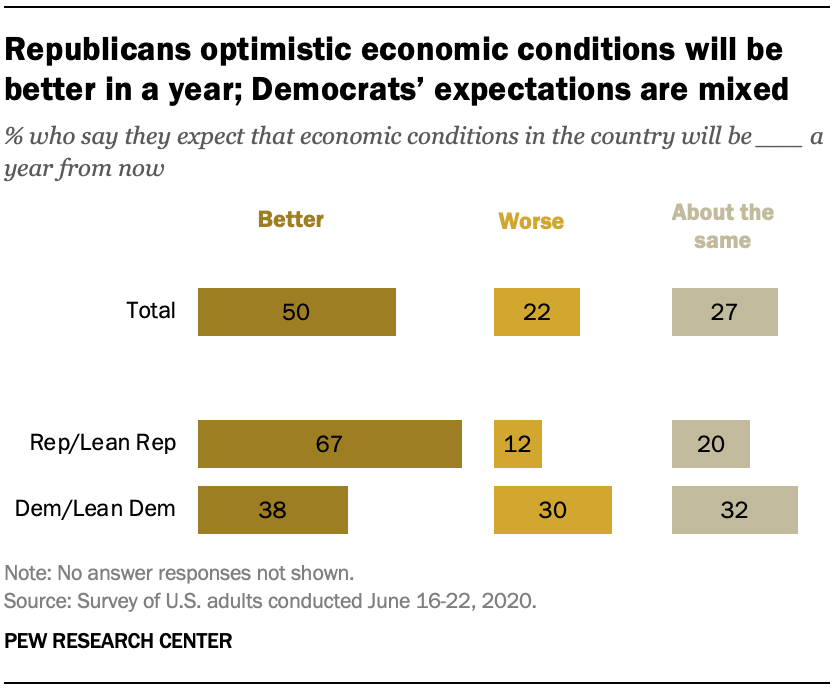

Despite the public’s continued negative assessment of the national economy, half of Americans expect that economic conditions in the country will be better a year from now (down modestly from the 55% who said this in April). Just 22% of the public thinks that economic conditions will be worse, and 27% think economic conditions will be about the same as they are today.

Despite the public’s continued negative assessment of the national economy, half of Americans expect that economic conditions in the country will be better a year from now (down modestly from the 55% who said this in April). Just 22% of the public thinks that economic conditions will be worse, and 27% think economic conditions will be about the same as they are today.

Most Republicans are optimistic about future economic conditions in the country: Two-thirds of Republicans say economic conditions in the country will be better a year from now, while 12% say they will be worse and 20% expect conditions to be about the same as they are today.

Democrats are more divided: While 38% think the economy will be better a year from now, 30% say it will be worse and 32% expect conditions will be about the same.

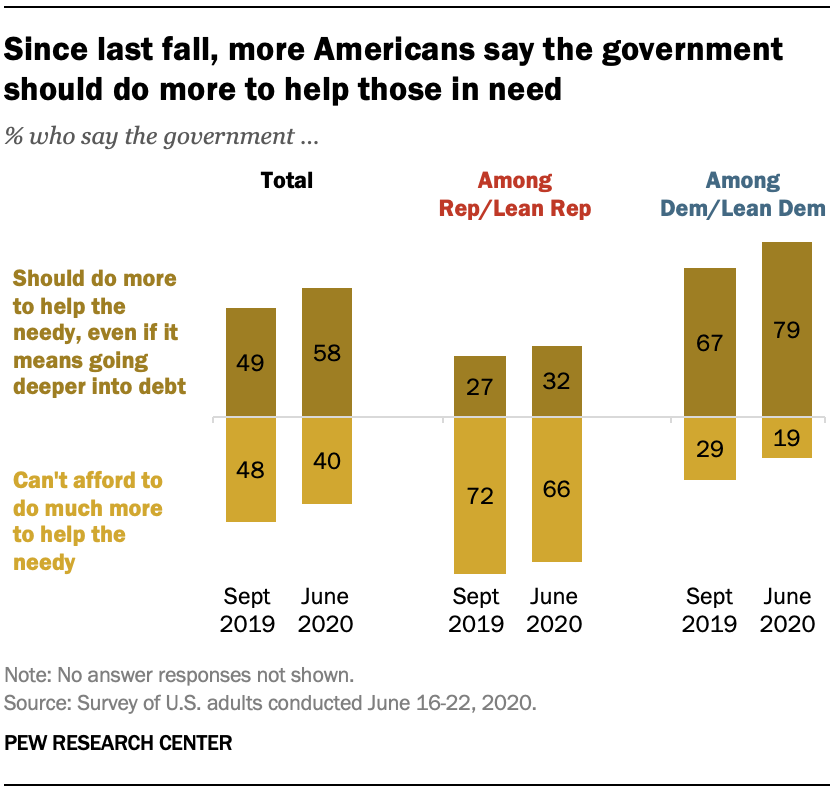

Americans’ views about aid to those in need have shifted since September, with more Americans now saying the government should do more to help the needy, even if it means going deeper into debt. Today, 58% of Americans say this, up from 49% last fall. Currently, four-in-ten Americans say the government today can’t afford to do much more to help the needy, down from 48% in September.

While there continue to be wide partisan differences in these views, the share saying more needs to be done to help the needy has increased in both parties.

While there continue to be wide partisan differences in these views, the share saying more needs to be done to help the needy has increased in both parties.

Today, about two-thirds of Republicans (66%) say the government cannot afford to do more to help those in need, while 32% say the government should do more – up from 27% in September.

The shift in these views is more pronounced among Democrats; nearly eight-in-ten Democrats (79%) now say more needs to be done to help the needy, up from 67% last fall (just 19% now say the government can’t afford to do more to help the needy).

Among Republicans, there are large divisions in views of whether the government should do more to help those in need by household income. While majorities of Republicans in upper-income (76%) and middle-income (68%) households say the government cannot afford to do more to help those in need, lower-income Republicans are divided: 50% say the government can’t afford to do more to help the needy, while 47% say the government should do more. There are minimal differences in these views by household income among Democrats.