Advertisement

Good morning and welcome to On Politics, a daily political analysis of the 2020 elections based on reporting by New York Times journalists.

Sign up here to get On Politics in your inbox every weekday.

-

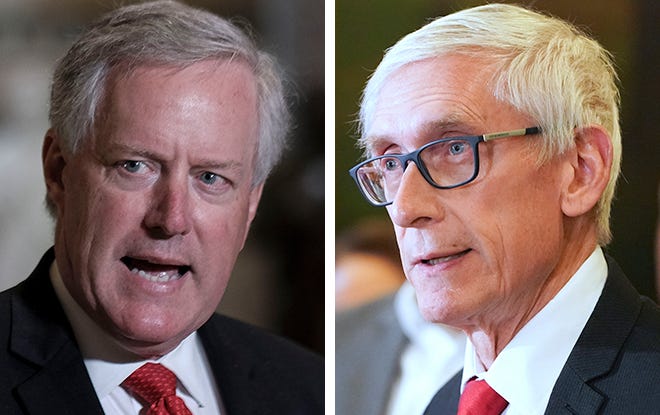

The debate over whether states should reopen their economies has hit a new frontier: Wisconsin’s conservative-leaning Supreme Court ruled yesterday that the state’s Democratic governor could not extend a stay-at-home order to May 26. The lawsuit, brought by state Republicans, was the first successful challenge of its kind, and could put wind in the sails of anti-shutdown conservatives in other states with Democratic governors. “An agency cannot confer on itself the power to dictate the lives of law-abiding individuals as comprehensively as the order does without reaching beyond the executive branch’s authority,” the justices wrote in handing down their 4-3 decision, split along ideological lines. The ruling did not include provisions for a stay, which would have allowed Republicans and Democrats to negotiate a compromise on reopening businesses in the state. “The lack of a stay would be particularly breathtaking,” one of the court’s more liberal justices wrote in dissent, “given the testimony yesterday before Congress by one of our nation’s top infectious disease experts, Dr. Anthony Fauci. He cautioned that if the country reopens too soon, it will result in ‘some suffering and death that could be avoided.’”

-

Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, has been speaking up in ways that someone in his position typically doesn’t. But these are not typical times. On Wednesday, he publicly urged Congress — for the second time in recent weeks — to take additional action to shore up the economy, saying that “the recovery may take some time to gather momentum.” Speaking at a virtual event for the Peterson Institute for International Economics, he praised Congress’s early response packages but argued that more legislation appeared necessary. “Additional fiscal support could be costly, but worth it if it helps avoid long-term economic damage and leaves us with a stronger recovery,” he said.

-

The House will hear testimony today from Rick Bright, a federal scientist and whistle-blower who said he had been removed as head of the government’s search for a coronavirus vaccine because he resisted devoting resources to an anti-malaria drug unproven against the virus. Bright plans to warn lawmakers today that “2020 will be the darkest winter in modern history” if the government does not take bolder steps to contain the virus, according to an advance copy of his testimony posted online on Wednesday. “Our window of opportunity is closing,” Bright wrote. “If we fail to develop a national coordinated response, based in science, I fear the pandemic will get far worse and be prolonged, causing unprecedented illness and fatalities.”

-

Michael Flynn’s legal problems aren’t over yet. The Justice Department moved this week to drop charges against Flynn, President Trump’s former national security adviser, who had already pleaded guilty to lying under oath. William Barr, the attorney general, recently told CBS News that F.B.I. agents had tried to “lay a perjury trap” in a 2017 interview with Flynn, during which he made the statements that eventually led to his guilty plea. But in a conversation with Justice Department lawyers just two days before they requested to drop the charges, Bill Priestap, the former head of F.B.I. counterintelligence who took notes during that interview, said this wasn’t true. When they moved to drop charges, Justice Department lawyers didn’t reveal that they had spoken to Priestap, or that he had disputed the idea that Flynn was set up. The story will now continue: The judge in the case, Emmet Sullivan, did not immediately endorse the Justice Department’s motion. He announced yesterday evening that he would appoint a former federal judge to argue against the government’s decision to drop charges.

-

Joe Biden has been relatively quiet since he began sheltering at home in March — but behind the scenes, one of his biggest priorities is shoring up support from liberal Democrats, whom he will need by his side in the general election. On Wednesday, Biden revealed the members of task forces in six policy areas that he had assembled alongside Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont; they’re full of progressive stalwarts known for policy positions far to the left of anything the former vice president has embraced, as well as more moderate stalwarts. The climate committee, for instance, will be run by a progressive-moderate tag team: Its co-chairs are Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the youngest and perhaps highest-profile progressive in the House, and John Kerry, the former secretary of state and longtime Biden ally. The Biden campaign in April raised over $60 million, a respectable sum, and it recently started its largest hiring spree yet. But Democratic Party officials remain worried that Biden may have difficulty catching up to the Trump campaign, which already has a robust staff and began the year with an enormous cash advantage.

-

Hospitals across the country have been filled to the brim with coronavirus patients — but many are facing revenue shortfalls nonetheless, driven by a decline in elective surgeries, typically a huge source of income under the United States’ private health care system. Federal relief grants to hospitals were supposed to help address those problems. But according to an analysis published on Wednesday by the Kaiser Family Foundation, this financial relief is disproportionately going to institutions that serve relatively affluent populations. The report found that hospitals that tend to rely mostly on revenue from private insurance have received more than twice as much federal grant funding per bed than hospitals with the lowest share of insurance income.

Photo of the day

Vice President Mike Pence wore a mask as he arrived at the White House on Wednesday.

By Manny Fernandez

HOUSTON — Few things define life in Texas more than red versus blue. Especially in these abnormal times.

At first, the Republicans who run Texas resisted shutting the state down over the coronavirus, while the Democrats who run the state’s major cities — Houston, Dallas, Austin, San Antonio — took charge and put local lockdowns and other restrictions in place.

It was a story repeated often in this divided country, as Democrats took a cautious, shutdown-oriented approach and Republicans feared that the cure was worse than the disease. But in Texas, everything is more pronounced, from the blue skies to the state pride to the pandemic politics.

So the Republican governor, Greg Abbott, finally issued a stay-at-home order, but later flexed his muscle over local officials with this caveat: His statewide virus-related policies superseded their city and county orders. And how did Democratic city leaders respond? Some of them went about their business and kept their local rules in place.

But the back-and-forth heated up on Tuesday.

The Republican attorney general, Ken Paxton, threatened legal action against city and county leaders in Austin, Dallas and San Antonio, telling them that their local restrictions were unlawful and more strict than those issued by Abbott. Face masks in public? The governor suggests wearing them, but does not require it, Paxton reminded officials. Municipal stay-at-home orders? The governor ended the state’s order this month, so the local ones are “unenforceable,” Paxton’s office noted.

Democrats disputed Paxton’s reading of their local orders. And some have pointed out that the attorney general who is telling them what is and what isn’t lawful is the same attorney general who was arrested on felony charges of securities fraud in 2015 after being indicted by a grand jury, in a long-running case that has dragged on.

Paxton has been battling Democratic leaders on other fronts, too. Yesterday he asked the state’s Supreme Court to prevent elections officials in at least five counties, including Dallas and El Paso, from providing mail-in ballots to voters who feared that casting their ballot in person might expose them to the virus.

On Politics is also available as a newsletter. Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox.

Is there anything you think we’re missing? Anything you want to see more of? We’d love to hear from you. Email us at onpolitics@nytimes.com.