MANCHESTER, N.H. — The Granite State has long prided itself as a place where voters get to measure a candidate up close, with retail politics giving the state outsize presidential primary power.

But this cycle’s daily drama out of Washington and increased attention to Iowa’s caucuses and efforts to meet rigorous Democratic debate thresholds (including pressure to establish a robust national fundraising presence) have posed challenges to New Hampshire’s old-fashioned political traditions — and to the candidates who count on them to break through.

Take Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey, for example, who did everything to set himself up for success here in the traditional sense. Booker hired staff early, was one of the first to knock on voters’ doors, earned impressive local endorsements and packed coffee shops and living rooms nearly a year before voting would begin.

Yet that knack for the kind of one-on-one politics this state expects wasn’t enough to sustain his candidacy in 2020’s increasingly nationalized primary cycle.

And for those still in the race, the demands of the 2020 cycle have affected how they campaign here like never before.

Candidates are increasingly forced to balance retail politics with attracting wider exposure — choosing between small house parties and national TV appearances, retail stops in rural towns and bigger rallies that draw attention.

A host of outside challenges have frustrated many candidates’ efforts here.

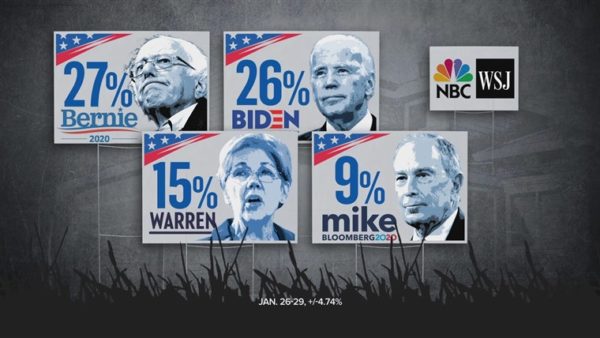

President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial has kept the four senators running for the Democratic nomination — Bernie Sanders of Vermont, Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Michael Bennet of Colorado and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota — off the trail for days at a time.

“The chaos out of Washington has over-saturated folks’ ability to pay attention to the more granular issues that we’re facing here,” state Sen. Jon Morgan told NBC News.

Add the fact that Iowa’s caucuses, eight days before New Hampshire’s Feb. 11 primary, have consumed the field, particularly for candidates like Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, whose candidacies are predicated on strong showings there.

Others, like former Vice President Joe Biden, with eyes on later contests like South Carolina and Super Tuesday have gambled that they don’t have to make New Hampshire a priority.

That’s why some campaigns are in overdrive trying to make up for the lack of personal connections traditionally expected by New Hampshire primary voters.

More than a half-dozen New Hampshire Democratic county and town chairs told NBC News that certain campaigns have impressed their communities, while others have fallen short. And they all agreed that retail politics still matter, particularly for undecided voters making last-minute decisions.

Some campaigns are tailoring their approaches to reflect their candidates’ personalities, with “night school” for supporters of plan-oriented Warren, “hot dish house parties” for Klobuchar, “MATH class” for entrepreneur Andrew Yang and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream socials for Vermont native Sanders.

Warren and Buttigieg have the strongest organizing operations, the Democratic chairs say, while Sanders has retained support from 2016, when he bested Hillary Clinton by more than 20 points.

“A lot of people never scraped the bumper sticker off from four years ago,” said Roger Lessard, co-chair of the Hillsborough County Democrats.

Sanders, now a well-known national figure, has stayed away this time from house parties — a local staple where candidates introduce themselves.

Instead, the campaign has focused its efforts on impressing national media with rally crowds featuring high-profile endorsers, along with turning out new voters and expanding the electorate to include more working-class people.

“If we can mobilize in time to vote, it will be the transformation that we need to happen,” Sanders campaign manager Faiz Shakir said in an interview. “If we do not, it’s going to be a tough slog.”

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

Still, activists here warn that organizing alone can go only so far. Showing up in person still matters, they say.

“In reality, you can have the best ground game in the world, but if you’re not reaching people and engaged, then you’re shot,” said Mike Machanic of the Grafton County Democrats. “If all you are is a paper candidate doing TV and not on the ground, then that’s a recipe for failure.”

Knute Ogren, the Democratic chairman of rural Carroll County, who has endorsed Buttigieg, noted that Biden had never visited his county. The other front-runners have visited all 10 counties this cycle.

While his campaign touts his talent for personal politics, Biden has opted for fewer traditional retail stops. In his only trip to New Hampshire in January, he held two larger community events, where he took no questions from voters. His campaign says Biden speaks with voters while shaking hands after larger events to ensure personal encounters.

Biden’s campaign has also relied on longstanding relationships with popular Democrats to act as campaign surrogates, including former Gov. John Lynch and former U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry.

“Joe Biden cannot be everywhere at once,” Biden organizer Noah Mayer said while out knocking on doors in Concord, emphasizing his own role as “the face of the campaign in the community.”

Warren has the benefit of being a next-door neighbor, but with that comes added pressure to impress — and win.

By making frequent trips in the state featuring one or two large events each time, Warren has drawn large crowds that attract national attention. But even with candid voter questions and hours spent in a “selfie line,” the organic connections are missing, at least in a traditional sense.

“I don’t think selfies are one-to-one contact,” Sullivan County Democratic Chair Judith Kaufman said.

Some argue that they are intimate enough, like Kathy Sullivan, New Hampshire’s member of the Democratic National Committee, who recently endorsed Warren. Sullivan said Warren has done a good job of “doing what people in New Hampshire expect.”

“She talks to everybody, anybody who wants to have a picture taken,” Sullivan said. “She stays till the end and she talks to them, which is not something that all candidates always have done.”

Buttigieg and Klobuchar, both Midwesterners focused on Iowa, have tried to stay attentive to New Hampshire.

Buttigieg, the only top-tier candidate to hold a bus tour across New Hampshire, went from near-anonymity a year ago to a true contender. Both then and now, he has sprinkled local stops at festivals and cafes with large town halls, tailoring outreach to redder parts of the state.

Klobuchar has held numerous meet and greets and has traveled throughout the state previously, but she was in New Hampshire for only one day in January. When she was in Washington for the impeachment trial, her campaign tried to recreate that level of intimacy through events like all-women organizing happy hours, weekly hot-dish house parties and “office hours” with local elected endorsers.

Some lesser-known candidates are hoping to break through in New Hampshire and gain national attention — and momentum — by investing in traditional retail politics.

Bennet, who has gone “all in” in the state as his path forward, said he recognizes the uphill climb he faces by sticking to the traditional playbook.

“I think that this whole election cycle might be a referendum on it,” Bennet said in an interview. “I think there is a real question about that. Have we nationalized the election? Has it become a social media election and a small-dollar fundraising election versus something else?”

Former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, who made the state’s ballot filing deadline with only hours to spare, has also honed a mostly New Hampshire strategy — albeit one that includes $2 million in Super PAC television ad buys.

“New Hampshire has made history more than once,” Patrick said in an interview at a community conversation in Milford. “Notwithstanding polls, notwithstanding conventional wisdom and punditry.”

For candidates like Bennet and Patrick, the local approach has not yet delivered results — both have been unable to crack more than 1 percent in polls.

Both Yang and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, have held more than 100 events in the state and hover at about 5 percent in New Hampshire polls.

Though most of her volunteers hail from out of state, Gabbard has made an effort to pop into local businesses and get to know communities here — even breaking away from what she calls “the usual traditional political haunts” by snowboarding and meeting potential voters atop a mountain in North Conway last week.

Billionaire Tom Steyer has made only six trips to the state since he announced his candidacy, but he’s spent at least $15 million on television ads in the Boston media market.

As televised debates and national storylines pull focus — especially in the key eight days between Iowa and New Hampshire — the question will be whether primary voters here have enough campaign information and candidate exposure to make final decisions.

“The national narrative is happening here, people are seeing it, but there’s a second thing that no one is seeing except for the people that are going to vote on primary day,” said Holly Shulman, a spokesperson for the New Hampshire Democratic Party.

“Anything is possible,” she said.

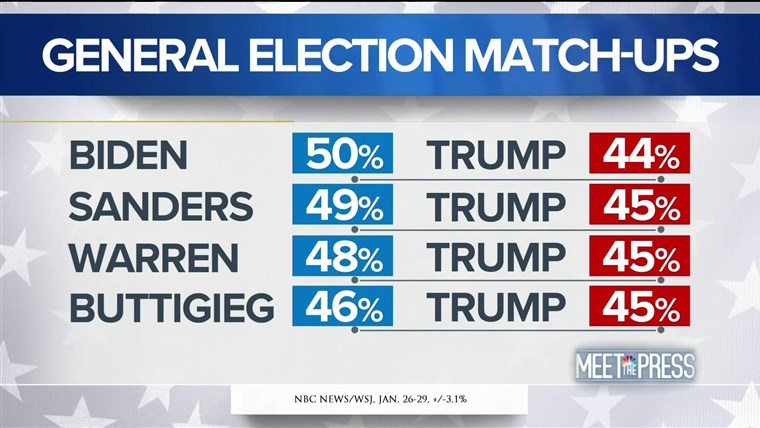

For the undecided voters here, the anxiety over making the wrong choice is amplified by their desire to beat Trump in the general election.

“All the campaigns are after us,” said Sue Veal, an undecided former Booker supporter from Rochester. “I’m just weary of second-guessing what Trump supporters and independents might or might not do.”

Secretary of State Bill Gardner, perhaps the fiercest defender of the state’s first-in-the-nation status, said that despite the challenges this year, New Hampshire can still deliver a powerful boost to candidates who make an effort here.

“It’s always been about the little guy. It’s always been about giving the person that doesn’t have the most fame or fortune a chance,” Gardner said.