This guide originally appeared in The Trailer newsletter; sign up to get it in your inbox.

The Democrats’ anguish about their primary system — Does it vet for the right qualities? Is it too slanted toward white voters? — is frequently directed at New Hampshire. By law, the state must hold its primary “seven days or more immediately preceding the date on which any other state shall hold a similar election,” which has stopped some more-diverse states from voting earlier. New Hampshire is 92 percent white, the least racially diverse of the early states, with most of its black, Latino and Asian voters concentrated in a few midsize cities.

New Hampshire has a semi-open primary, giving voters who have not registered with the Democratic Party their loudest voice of any of the first four states. Just 60 percent of New Hampshire primary voters who pulled a Democratic ballot were registered with the party in 2016. The independent streak helped Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) win by a landslide; he won registered Democrats by a single percentage point and crushed Hillary Clinton by 45 points with independents.

The victory in 2016 was the most lopsided in the 100-year history of the primary. Sanders won 60 percent of the vote and all but six of the state’s 221 towns; Clinton had the endorsements of every major party leader, including the Democrats who now make up New Hampshire’s all-blue delegation to Congress. All of them — Sen. Maggie Hassan, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, Rep. Ann Kuster and Rep. Chris Pappas — are neutral in 2020.

The last primary had an obvious direction and momentum that simply hasn’t been replicated in 2020. No Democrat has built a lead outside the margin of error since July, before the bounce from former vice president Joe Biden’s announcement had faded. In an average of polls, the lead has switched three times since October, from Biden, to Sen. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.), to former South Bend, Ind., mayor Pete Buttigieg, and back to Sanders.

In another year, Sanders’s proven strength in New Hampshire could scare off some rivals. But this year, in a crowded field, Sanders has never come close to his 2016 strength, shedding more than half of his old support. But without a binary, who’s-going-to-stop-Clinton contest to focus on, New Hampshire Democrats have been flitting more among candidates, and independents have joined them.

That’s been tremendously helpful to Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (Hawaii), a onetime Sanders supporter who is now friendlier to conservatives (on abortion, on whether to impeach the president) than anyone else in the race. It’s also been a solace to Sen. Michael F. Bennet (Colo.), who is pitching himself as a president so pragmatic and low key that “you won’t have to think of me for 2 weeks at a time.” There are plenty of voters here who aren’t too liberal but will pull a Democratic ballot. Since January 2017, when the president was sworn in, Democratic registration has shrunk by 3,071 voters, Republican registration has shrunk by 15,554 voters, and 9,529 new voters have climbed onto the rolls with no party registration.

They’re in high demand. This is a primary, after all, with none of the time or organizing demands of a caucus state. Late-breaking voters, people who maybe paid attention for only the final week of the contest, can change everything. It happened in 2008, when Barack Obama surged in polling over Clinton in the days after his Iowa win, but then key voters came back to her. (Both campaigns’ internal polling had put Obama ahead.) It nearly happened in 2004, when Howard Dean, humiliated by a loss in Iowa, campaigned hard and cut John F. Kerry’s lead in half. The reverse happened in 2016, when Sanders’s overwhelming organization made the difference between a win in the high single digits and a 21-point rout that raised questions about Clinton as a “front-runner.”

All of this happens in a state where most voters live within a 90-minute drive of one another. New Hampshire’s tourism department splits it into seven regions, which don’t quite overlap with its 10 counties. The vast majority of voters live south of Lake Winnipesaukee, away from the tourist towns, in small cities and suburbs around Boston’s media market. There is plenty of political diversity in towns that otherwise look pretty similar; walking from Merrimack (pop. 25,660) to Amherst (pop. 11,201) means leaving deep-red Trump Country to enter a place that abandoned the GOP for Clinton.

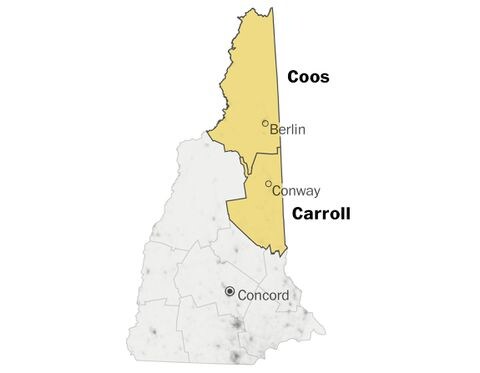

The north country’s population is shrinking, and few voters remember a time when it wasn’t. Berlin, an old paper mill city, has lost half its population since the 1930s. Dixville Notch, which became famous for its unique midnight vote, found just enough residents to hold it this year.

There are not many Democratic votes to win here, just 6 percent of the total usually cast, and there’s been relatively little campaigning, even though it’s the sort of rural, Obama-to-Trump place they highlight in other states. How much time should any candidate spend in a region with fewer Democratic votes than Manchester? There’s a saying, cruel but often followed, that even reporters shouldn’t go north of the White Mountains for candidates polling under 10 percent.

Berlin and Conway are the only major population centers here, but it’s worth watching who turns out. Berlin, for example, cast 2,741 votes in the 2008 primary, and just 1,896 in the Clinton-Sanders race. If Sanders has been able to organize disaffected voters, it’ll be seen up here; if a candidate like Andrew Yang has won over the people who gave up on politics or gave President Trump a chance in 2016, he’ll do well in Coos and Carroll.

- 2016: Sanders 63 percent, Clinton 35 percent

- 2008: Clinton 38 percent, Obama 35 percent, John Edwards 19 percent

- 2004: Kerry 39 percent, Dean 27 percent, Clark 14 percent, Edwards 11 percent

The Connecticut River Valley, a string of farms and college towns, is the most liberal part of the state. Sanders got his biggest margins here, Obama won even while losing statewide to Clinton, and Dean edged out Kerry. Two of those candidates were Vermonters, which helped; Sanders’s first campaign events here were long weekend road trips. But the electorate is usually looking for a left-wing candidate, even when it can’t find a Vermonter.

The region casts roughly 19 percent of the state’s Democratic primary votes, with the biggest pile coming out of Keene, a city whose isolation and low prices have also made it a beacon for libertarians. The three counties where most valley residents live have plenty of internal differences — Sullivan County is more rural and backed Trump over Clinton — but tend to vote as a unit in a Democratic primary.

Center-left candidates tend to struggle here, and there are plenty of towns where Clinton, in 2016, didn’t reach 25 percent of the vote. If there is a strong left-wing vote, but it splits, the map will probably show Warren performing strongly in other liberal parts of the state but Sanders dominant along the “Conn River.”

- 2016: Sanders 68 percent, Clinton 30 percent

- 2008: Obama 42 percent, Clinton 33 percent, Edwards 16 percent

- 2004: Dean 38 percent, Kerry 32 percent, Wesley Clark 12%, Edwards 10 percent

Capitol cities tend to lean left, and Concord fits the mold: It backed Clinton over Trump by 25 points in 2016, helping her win a county that casts 12 percent of the state’s Democratic primary vote. More telling was Bow, an example of the suburbs where Mitt Romney ran stronger than Trump was ever able to and where Clinton had come closest to beating Sanders. (He got the win by just 61 votes.)

Although the county has been politically competitive for years, Democrats now control two-thirds of its state legislative districts, thanks to those same Trump-phobic independents and former Republicans.

- 2016: Sanders 58 percent, Clinton 40 percent

- 2008: Obama 38 percent, Clinton 36 percent, Edwards 17 percent

- 2004: Kerry 38 percent, Dean 27 percent, Edwards 13 percent, Clark 12 percent

No region has less power in a Democratic primary. Dominated locally by Republicans, it casts just 4 percent of the Democrats’ primary vote and gets relatively few visits. It’s distinct enough from nearby Merrimack County to resist being lumped in, with fewer votes, but it’s a good place to watch for turnout patterns: No Democrat, not even the three who have won elections in a neighboring state, have an advantage here.

- 2016: Sanders 61 percent, Clinton 36 percent

- 2008: Clinton 37 percent, Obama 37 percent, Edwards 19 percent

- 2004: Kerry 38 percent, Dean 25 percent, Edwards 13 percent, Clark 13 percent

Connecting the sea coast area to the lake country, Strafford casts 10 percent of the primary vote, and half of that comes from three towns: Dover, Rochester and Durham. The latter town includes the University of New Hampshire, which is enough to give it a big bloc of liberal voters but not enough to dominate the county. (It’s the state’s biggest university, and it enrolls less than half as many students as Iowa State University.)

The strong Democratic lean of the county can mean very different things with different primary lineups. In 2004 and 2008, Kerry and Clinton ran well ahead of their statewide numbers here, as active Democrats moved over to the candidates they knew best. But in 2016, Sanders blew Clinton away. A key city was swingy Rochester, which broke heavily for Clinton in 2008, then gave Sanders a 21-point landslide. Like Belknap, Strafford is a good place to monitor how much of the 2016 vote was an endorsement of Sanders’s policies and how much was an anti-Clinton message vote that will be hard to replicate in 2020.

- 2016: Sanders 63 percent, Clinton 35 percent

- 2008: Clinton 41%, Obama 34%, Edwards 18%

- 2004: Kerry 40%, Dean 24%, Edwards 13%, Clark 13%

The biggest Republican margins come from some of these towns, close to Boston and easy places to escape high-tax Massachusetts. Democrats dominate the seacoast towns like Rye and Portsmouth, while Republicans win in suburban cities like Derry. What they often have in common is money, with a median income of about $90,000, the highest in the state, doubling the average income in rural Coos County.

A full 22 percent of New Hampshire’s Democratic voters live in a county that gets most of its news from Boston, and plenty of its residents, too; former senator from Massachusetts Scott Brown moved to Rye before making an unsuccessful 2014 run for one his new state’s Senate seats.

This electorate stands out because it’s not been particularly interested in insurgent candidates or underdogs. Clinton ran strongest here, in both of her presidential bids, and ran further ahead on the seacoast. (It was in Portsmouth, shortly before the 2008 primary, where she teared up at a question about how hard campaigning was, a show of emotion that helped her win.)

- 2016: Sanders 57 percent, Clinton 42 percent

- 2008: Clinton 42 percent, Obama 35 percent, Edwards 17 percent

- 2004: Kerry 41 percent, Dean 23 percent, Clark 12 percent, Edwards 12 percent

The state’s most populous county casts 27 percent of the Democratic primary vote; together, the Boston suburbs of the “southern tier” contain about half of all New Hampshire voters. Hillsborough has moved to Rockingham’s left, though, with Democrats pushing the GOP aside in cities such as Manchester and Nashua. Just five years ago, Republicans sat in the mayor’s office of both cities. Democrats now run both, with Republicans failing even to find a candidate in this year’s Nashua elections.

In the primary, the electorate is much more centrist, rejecting left-wing candidates by the same big margins as Rockingham County. But there are far too many votes for any candidate to write it off.

Back in 2016, even though Sanders did worse in Hillsborough than in other parts of New Hampshire, he united every sort of anti-Clinton voter. She won just one big town, Bedford, and lost others by slightly smaller margins than her statewide numbers. Sanders pulverized her in the smallest towns and took Manchester by the same margin Clinton once won it by over Obama: 15 points.

- 2016: Sanders 57 percent, Clinton 41 percent

- 2008: Clinton 42 percent, Obama 35 percent, Edwards 16 percent

- 2004: Kerry 40 percent, Dean 22 percent, Edwards 13 percent, Clark 12 percent

After all of that, after eking out every vote from Salem to Pittsburg, New Hampshire offers momentum more than anything else. The state will send just 24 pledged delegates to the Democratic National Convention, the least of any early-voting state. But it is brutally effective at shrinking the field. In this century, no more than five Democrats have escaped Iowa with viable campaigns, and no more than three have gotten out of New Hampshire.

No Democrat from a neighboring state (Maine, Massachusetts, Vermont) has ever lost New Hampshire and gone on to take the nomination; even a weaker-than-expected win, like Ed Muskie’s in 1972 or Paul Tsongas’s 20 years later, can start the clock running out for a local candidate.

Story by David Weigel. Get his Trailer newsletter for insight from the campaign trail and around the country.

Credits: David Weigel