Advertisement

News Analysis

Presenting himself as a warrior against identity politics, the president has increasingly made appeals to the grievances of white supporters a centerpiece of his re-election campaign.

WASHINGTON — After a summer when hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets protesting racial injustice against Black Americans, President Trump has made it clear over the last few days that, in his view, the country’s real race problem is bias against white Americans.

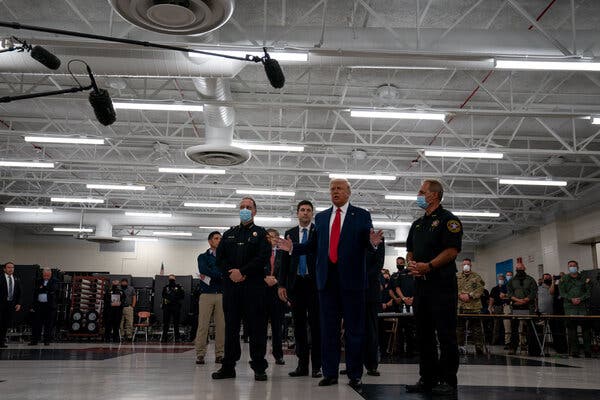

Just days after returning from Kenosha, Wis., where he staunchly backed law enforcement and did not mention the name of Jacob Blake, the Black man shot seven times in the back by the police, Mr. Trump issued an order on Friday to purge the federal government of racial sensitivity training that his White House called “divisive, anti-American propaganda.”

The president then spent much of the weekend tweeting about his action, presenting himself as a warrior against identity politics. “This is a sickness that cannot be allowed to continue,” he wrote of such programs. “Please report any sightings so we can quickly extinguish!” He reposted a tweet from a conservative outlet hailing his order: “Sorry liberals! How to be Anti-White 101 is permanently cancelled!”

Not in generations has a sitting president so overtly declared himself the candidate of white America. While Mr. Trump’s campaign sought to temper the culture war messaging at the Republican National Convention last month by showcasing Black and Hispanic supporters who denied that he is a racist, the president himself has increasingly made appeals to the grievances of white supporters a centerpiece of his campaign to win a second term.

The message appears designed to galvanize supporters who have cheered what they see as a defiant stand against political correctness since the days when he kicked off his last presidential campaign in 2015 by denouncing, without evidence, Mexicans crossing the border as “rapists.” While he initially voiced concern over the killing of George Floyd under the knee of a white police officer in Minneapolis this spring, which touched off nationwide protests, he has focused since then almost entirely on defending the police and condemning demonstrations during which there have been outbreaks of looting and violence.

He has described American cities as hotbeds of chaos, played to “suburban housewives” he casts as fearful of low-income people moving into their neighborhoods, sought to block a move — backed by the Pentagon and Republican lawmakers — to rename Army bases named for Confederate generals, criticized NASCAR for banning the Confederate flag, called Black Lives Matters a “symbol of hate” and vowed to strip funding from cities that do not take what he deems tough enough action against protesters.

In effect, he is reaching out to a subset of white voters who think the news media and political elites see Trump supporters as inherently racist. Mr. Trump has repeatedly rejected the notion that America has a problem with systemic racial bias, dismissing instances of police brutality against Black Americans as the work of a few “bad apples,” in his words.

“Trump is the most extreme, and he has done something that is beyond the bounds of anything we have seen,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, the president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. “Playing with racism is a dangerous game. It’s not that you can do it a little bit or do it slyly or do it with a dog whistle. It’s all dangerous, and it’s all potentially violent.”

Aides said Mr. Trump’s actions were aimed at eliminating pernicious views that actually exacerbate prejudice. “President Trump believes that all men and women are created equal, and he will stand against anti-American philosophies of all kinds that promote racial division,” Kayleigh McEnany, the White House press secretary, said on Sunday.

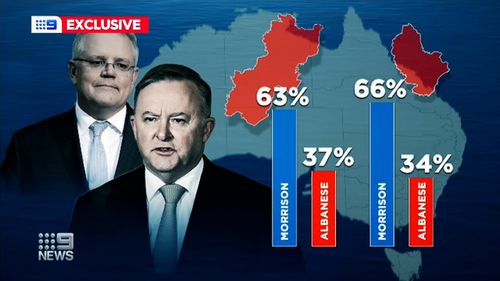

Public views of Mr. Trump flow through a racial prism. A poll by CBS News last week found that 66 percent of registered voters believed Mr. Trump favored white people, versus 4 percent who said he worked against their interests. By contrast, 20 percent thought he favored Black people and 50 percent said he worked against Black people. Among Black voters, 81 percent said he worked against their interests.

In the poll, Mr. Trump led former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., his Democratic challenger, among white voters by 51 percent to 43 percent, but trailed among Black voters with just 9 percent support, compared with 85 percent for Mr. Biden. Among Hispanic voters, Mr. Biden led by 63 percent to 25 percent.

The president’s latest order came as a book to be published on Tuesday by Michael D. Cohen, his former lawyer and fixer, describes a dismissive attitude toward nonwhite voters during the 2016 campaign. They were “not my people,” Mr. Cohen quotes Mr. Trump as saying. “I will never get the Hispanic vote,” Mr. Trump added, according to the book. “Like the Blacks, they’re too stupid to vote for Trump.”

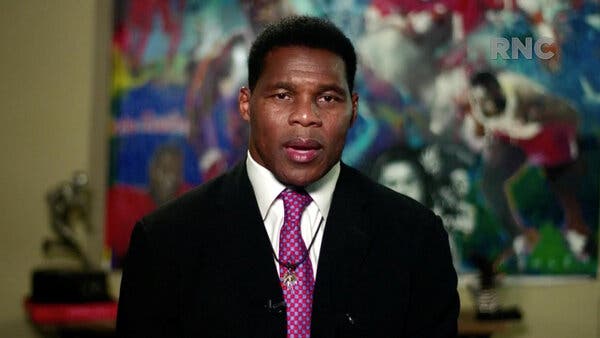

The president’s approach in recent days seems to belie the Republican convention programming that sought to soften his image on race by featuring validators like Herschel Walker, the onetime football star, and Vernon Jones, a Black Democratic state legislator from Georgia, who testified to Mr. Trump’s friendship and support for people of all races.

The president often makes the unfounded assertion that he has done more for Black Americans than any president other perhaps than Abraham Lincoln. He cites his support for funding for historically Black colleges and universities, his signature on legislation overhauling criminal justice sentencing and an unemployment rate for Black people that dropped to record lows on his watch, continuing a trend that had begun under his predecessor, until it rose again with the pandemic-related economic slowdown.

But analysts said the convention had been aimed at making it easier for white voters uncomfortable with Mr. Trump’s history on race to support him and that it might have appealed to nonwhite voters who bristle at the so-called cancel culture that has become a favorite target of the right.

Like other policies put forth with little advance notice, Mr. Trump’s focus on diversity training seems to have originated with something he saw on Fox News. On Tuesday night, Tucker Carlson interviewed Christopher F. Rufo, a conservative scholar at the Discovery Institute who criticized what he called the “cult indoctrination” of “critical race theory” programs in the government.

“It’s absolutely astonishing how critical race theory has pervaded every institution in the federal government, and what I’ve discovered is that critical race theory has become in essence the default ideology of the federal bureaucracy and is now being weaponized against the American people,” Mr. Rufo said on the program.

On his website, Mr. Rufo identified six agencies that had conducted training sessions that he said asserted that America is inherently racist and promoted concepts like unconscious bias, white privilege and white fragility. At the Treasury Department, for instance, he said employees had been told that “virtually all white people contribute to racism” and that white staff members should “struggle to own their racism.”

Mr. Trump’s memo on Friday adopted much of this language, attributing it to “press reports.” The memo, signed by Russell T. Vought, the director of the Office of Management and Budget, said “this divisive, false, and demeaning propaganda of the critical race theory movement is contrary to all we stand for as Americans and should have no place in the Federal government.”

Mr. Trump wrote or reposted roughly 20 Twitter messages about the memo on Saturday and on Sunday said the Education Department would investigate schools that use curriculum from the 1619 Project by The New York Times Magazine, an effort to look at American history through the frame of slavery’s consequences and the contributions of Black Americans.

Critics said the president’s move was a transparent play for white votes with less than two months until the Nov. 3 election.

“To say antiracism is anti-American is to say racism is American, which is to say Trump wants white Americans to be racist,” said Ibram X. Kendi, the author of “How to Be an Anti-Racist” and director of the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research. “And that’s precisely the point. He’s relying on manipulating the racist fears of white voters to win them over. Once white people lose those fears through interventions like trainings, Trump loses their votes.”

Mr. Rufo, though, said on Sunday that Mr. Trump was pitting his America First narrative celebrating the nation’s heritage against what he called the Black Lives Matter narrative that America was founded on racism. “The president is framing the election for voters in these terms,” he said. “Do they want to preserve the American way of life or do they want to burn it down?”