Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of profiles of the leading Honolulu mayoral candidates.

Keith Amemiya has been close to politics for a long time. Now he’s stepping into the fray himself.

The first-time candidate, who earned widespread praise when he led Hawaii high school sports, is running for Honolulu mayor on a message of change.

“We need new leadership,” he said in a recent interview with Civil Beat and Hawaii News Now. “We need a fresh perspective. We need to restore trust in government.”

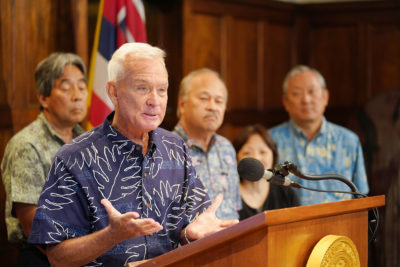

Keith Amemiya is best known for running the Hawaii High School Athletics Association for 12 years.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

If elected, Amemiya said, his No. 1 priority would be an issue his predecessors haven’t had the “political will” to effectively tackle: housing and homelessness. He would also boost city spending on mental health care, support increased fees on visitors to promote sustainable tourism, reform the Department of Planning and Permitting and finish the rail project “responsibly.”

In his stump speech, Amemiya says working class families are his focus.

“They have to decide between paying the rent versus paying for their car payment, whether to pay a medical bill or put food on the table,” he said. “We need to do whatever we can to ensure that today’s families have the same opportunity to live, work, play and raise a family like many of us have been fortunate to do.”

While Amemiya says he represents a new chapter for the city, he’s as close to local politics as one can be without actually having run for office before.

He’s the son of former Hawaii Attorney General Ronald Amemiya and the cousin of Roy Amemiya, Mayor Kirk Caldwell’s managing director. And for years, Keith Amemiya has been a generous donor to the political campaigns of Hawaii’s power players.

Amemiya donated thousands to Mayor Kirk Caldwell’s political campaigns.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

Since 2007, he has donated $63,400 to local and state political campaigns, according to state data. Over the years, Amemiya has given the most – $12,500 – to Caldwell, followed by $12,000 to Neil Abercrombie and $7,050 to his current opponent in the mayor’s race, Mufi Hannemann.

He has also supported influential legislative leaders, including House Finance Chair Sylvia Luke and Senate Ways and Means Chair Donovan Dela Cruz. He hedged his bets in the 2018 gubernatorial election, donating $1,000 each to David Ige and Colleen Hanabusa, who is also running against him for mayor.

Amemiya has donated thousands more toward federal races. Until last year, he was the campaign treasurer for U.S. Sen. Brian Schatz.

Elected officials have also chosen Amemiya to serve on citizen boards. Hannemann appointed him to the Honolulu Police Commission in 2006, and Abercrombie appointed him to the Hawaii Board of Education in 2011. Ige appointed him to the Aloha Stadium Authority board.

In 2008, Amemiya resigned as vice chairman of the Honolulu Police Commission after the Honolulu Ethics Commission launched a conflict of interest investigation. Amemiya had accepted a $25,000 donation from the police union for an HHSAA fundraiser. Amemiya said he didn’t think the gift was a problem because it went directly to schools, the Honolulu Advertiser reported, but said he resigned to eliminate unnecessary distractions.

Amemiya is also well-connected in the private sector.

The contributions to his campaign feature thousands of dollars from CEOs and other prominent business leaders. And for years, he’s worked closely with wealthy businessmen Colbert Matsumoto and Duane Kurisu.

“They’re about as establishment as you can get,” said Colin Moore, director of the University of Hawaii Public Policy Center. “I think he’s made efforts to present himself as the outsider, which is patently absurd.”

Amemiya said no one should be concerned about him being a puppet for corporate interests. Much of his support is at the grassroots level, he said, with many people from his high school athletics days supporting his run.

He also secured endorsements from several unions including the state’s largest, the Hawaii Government Employees Association, the United Public Workers, and the unions representing plumbers and fitters, painters and dock workers.

“The bulk of my relationships and friends are not wealthy developers or business folks,” he said. “Colbert Matsumoto is certainly a friend who has always been good to me, but I won’t be beholden to him or anyone else like him if elected mayor.”

‘A Second Lease On Life’

Amemiya, 54, has made the story of his upbringing a central part of his campaign.

In television ads, he talks about how his mother suffered from mental illness and was on the brink of homelessness as a result.

Amemiya said he “was getting shuttled from relative to relative” and later moved in with the family of his best friend, Chris Kobayashi.

To this day, Amemiya considers Bert T. Kobayashi Jr., Chris’s father and a prominent local attorney, to be his hanai father. Amemiya named his son after Chris. He says the Kobayashis gave him a “second lease on life” and what they taught him about compassion still guides him.

“A lot of kids come from broken homes or a dysfunctional family, and they don’t have the guidance that they should be getting,” he said. “Sometimes it takes someone like a teacher or a coach to help them navigate their adolescence and steer them into the right direction in adulthood.”

At his campaign kickoff, Amemiya talked about his mother’s mental illness.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

The Kobayashis enabled Amemiya to transfer from public school to Punahou where he graduated in 1983. He then studied finance at the University of Hawaii Manoa and earned a law degree from the UH law school.

Amemiya worked as an attorney in commercial litigation for several years before he was hired in 1998 to lead the Hawaii High School Athletics Association.

Once a state agency, HHSAA became a nonprofit in 1996 and needed a leader who could tap into funds in the private sector. Considered an unusual pick for the job at first, Amemiya is now widely credited with saving high school sports.

In his 12 years at the helm, Amemiya implemented division classifications and established state championships for girls sports. Most notably, after the 2008 financial crash, he led a fundraising campaign that brought in more than $1.5 million to support athletic programs that otherwise were on the chopping block.

“Amemiya’s greatest skill, perhaps, is the ability to bring disparate entities together for the common good,” the Honolulu Star-Bulletin’s Paul Honda wrote in 2009. “Hawaii’s children are better for it.”

Amemiya and his wife donated a $20,000 scoreboard to Roosevelt High School in 2006. And following in the footsteps of the Kobayashis, he welcomed a student from Molokai into his home so she could train on Oahu. That student later received a UH scholarship and returned to Molokai where she is a public school teacher and coach.

In early 2010, Amemiya left HHSAA to join the UH Board of Regents where he worked until 2012. Most recently, Amemiya made more than $200,000 a year as a senior vice president at Island Holdings, the parent company of Island Insurance, Atlas Insurance Agency, IC International, Pacxa, and Tradewind Capital Group.

Colbert Matsumoto is the chairman of Tradewind Capital Group and former chairman of Island Insurance Co.

Amemiya said he oversaw operations, sat on the boards of Atlas and Pacxa, gave legal advice and brought in new clients. He also led company community service projects, he said. He resigned from his position last year to be a full-time mayoral candidate.

Amemiya lives in Pauoa with his wife, Bonny Amemiya. She is the chief financial officer at aio, a group of companies founded by Duane Kurisu that publishes Honolulu Magazine and Hawaii Business Magazine among other titles.

Housing For All

If elected, Amemiya said a major focus for his administration would be addressing the high cost of living. That starts with housing, he said.

“There are many things that are more expensive in Hawaii than on the mainland, but none impacts a family’s finances more than the cost of housing,” he said.

Amemiya is the only top-tier candidate with a written plan to fill the 22,000-unit housing need on Oahu. His Housing For All plan includes:

- Aggressive enforcement on short-term vacation rentals

- Taxing vacant investor units

- Limiting permits on luxury developments

- City-developed affordable housing

- Investments in infrastructure to facilitate affordable development

- Hiring more staff at the Department of Planning and Permitting to cut through backlogs

- Waiving sewer, park and other fees for affordable projects

- Rezoning land within the urban core to allow more density there and “keep the country country”

Asked about his past work on housing issues, Amemiya pointed to Tradewind Capital’s involvement in the development of 801 South Street in Kakaako. The project was launched as a workforce housing complex, meaning 75% of the units had to be sold to people making 140% of the area median income or below. In 2015, that would’ve been about $97,000 for a two-person household, according to the Hawaii Community Development Authority.

The project was criticized though after owners who bought units for cheap resold them at a profit a short time after their purchase.

And the market rate units ended up in the hands of the developers’ friends. Amemiya was one of them. In 2015, he and his wife paid $375,300 for a one-bedroom unit on the 44th floor, property records show.

Other connected people got units too, including Roy Amemiya’s son; Matsumoto; John Waihee IV, the son of the former governor who’s also an Office of Hawaiian Affairs elected board member; Gary Kurokawa, the mayor’s chief of staff; and Tracy Kubota, then deputy director of the Department of Enterprise Services.

Amemiya’s company helped develop 801 South Street, which was meant to be workforce housing.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

Amemiya said he bought a market rate unit and still owns it. Its current assessed value is about $580,000, according to county records. In the future, he said, he’ll give it to his son.

“We didn’t sell it like we could have for a high profit,” he said. “We’re renting it to a local family.”

The project highlights the reality of developing affordable housing, Amemiya said.

“Developing high rise condominiums is financially risky,” he said. “In order for developers to agree to a project, you sometimes need to allocate a portion of the project to the open market.”

The high cost of land makes it difficult for private developers to build 100% affordable housing, he said. That’s why, Amemiya said, he is committed to having the city itself build more public housing. The city has already developed projects like the Kumu Wai building for kupuna, but Amemiya thinks the city should do more.

“Because the city will be developing it, the incentive to make a profit is not there,” he said.

To head off a wave of homelessness related to the current economic crisis, Amemiya said the city needs to work with the state and federal government as well as nonprofits.

As for the more than 4,400 people who are already homeless on Oahu, he said the city should be focusing on creating more shelter space and making available more mental health and addiction services. Amemiya said he would allocate city resources towards health-based solutions.

“Homelessness is such a big problem that we can’t waste time pointing fingers as to who is ultimately responsible,” he said. “We all need to be responsible.”

He would also like to replicate the success of Kahauiki Village, the plantation-style community that came about through Kurisu’s partnership with the city and state. At Island Holdings, Amemiya said he participated in the development of that project.

Caldwell has made the sweeping of homeless encampments a key piece of his response to homelessness. Amemiya stopped short of saying he would stop the sweeps, but said he hopes focusing on shelter and housing will make them unnecessary.

“I’m not keen on the idea of shoving the homeless from place to place and then they end up in the original spot,” Amemiya said.

A Democrat ‘For Change’

A joint Civil Beat/Hawaii News Now poll in May found that many voters were still undecided, but businessman Rick Blangiardi and Hanabusa were the respondents’ top picks. Amemiya came in third with 10% of respondents saying they plan to vote for him. Hannemann hadn’t yet announced his candidacy.

In the nonpartisan race, Amemiya is the only candidate who has advertised that he is a Democrat. It highlights the fact that he is likely the most liberal candidate in the race, said UH’s Moore.

“There is no one to his left,” Moore said. “He can get all of those voters if he can convince folks he’s competent to do that job.”

Amemiya says he is the fresh face city hall needs.

Amemiya is making that argument by leaning on his nonprofit background.

Financially, the experience isn’t comparable. The HHSAA’s revenue during Amemiya’s tenure was under $2 million – a small fraction of the city’s nearly $3 billion operating budget.

But Amemiya said the job was more than that. He oversaw programs covering 95 public and private high schools statewide and 33,000 student athletes, he said. It required working closely with schools, the county government, the Legislature and the governor’s office to obtain funding and advocate for program and policy changes.

“Just like being mayor, you have to deal with many different constituencies,” he said of his old job. “You’re under tremendous pressure. High school sports means a lot in Hawaii to the community.”

Overall, Amemiya said his lack of government experience is a plus.

“They tout the wrong kind of experience,” he said of politicians, without naming names. “They’re experienced in being involved in politics their whole career. They’re experienced in running for different offices every election cycle. They’re experienced in leaving their office to run for another office during the term that they’re sitting in office.”

Amemiya’s opponents Hanabusa and Hannemann have both been perpetual political candidates and have at times left jobs to run for office. Hanabusa resigned from the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation board to run for Congress, a race she won. Hannemann resigned halfway through his second mayoral term to run for governor. He lost.

The first order of business for the next mayor will be addressing the ongoing pandemic and the financial crisis it has caused. Amemiya said he would listen to the advice of public health officials to reopen businesses safely.

“The key to reopening the economy is testing, contact tracing, wearing masks and social distancing,” he said.

The city should also be more aggressive in getting federal funds into the pockets of the people, Amemiya said.

“The need is so great,” he said.

Amemiya said it’s too soon to say where cuts may be needed. He hopes to make the city government more efficient with technology. He would consider property tax deferrals for hotels that have shut down or sat mostly vacant. Property tax increases would be “a very last resort” for both residences and hotels, he said.

As a nationwide movement demands more accountability from police departments, Amemiya said it’s worth evaluating the structure of the Honolulu Police Department. He supports a ban on chokeholds, a requirement for officers to intervene when their peers are misbehaving, and implicit bias training not only for police but all city employees. He also supports House Bill 285, which makes public the names and details of police misconduct cases. State lawmakers passed the bill, which is awaiting a decision by Ige.

According to Honolulu Police Chief Susan Ballard, the department already has a ban on chokeholds, except in cases that warrant deadly force; officers are required to intervene; and the department receives bias training. A committee is reviewing HPD’s use of force policy, but in general, Ballard has stated the department doesn’t need the broad reforms that may be necessary on the mainland.

When Amemiya was on the Police Commission, he said his impression was the vast majority of officers were honest and free of corruption. But the criminal conspiracy committed by former Police Chief Louis Kealoha and his wife, former prosecutor Katherine Kealoha, proves there’s room for improvement.

“It’s clear we need to constantly remain vigilant,” he said.

As mayor, Amemiya said he would like to boost citizen participation in government. He envisions an Office of Community Engagement to hear resident feedback and concerns. It would be funded with existing resources in the mayor’s office, he said. He also supports making public meetings in the evenings when people aren’t working and allowing people to sign up to testify at a designated time so they don’t have to wait around.

Those measures would go a long way to preempt misunderstandings and disputes that often come to a head when a project is already underway, he said.

“I’m a strong believer in proactive communication with communities,” he said. “True or not, the public feels the city, or government in general, just announces things and says, ‘It’s going to happen,’ without getting public input.”

Ultimately, Amemiya said he wants to change Honolulu so that working families don’t have to move to the mainland to have a decent life.

“I feel that people who have the power to affect change should do so, and we need to do what we can to make life better for them,” he said. “And that’s why I’m running.”

Read other profiles in this series:

• Mufi Hannemann: He Was Mayor Once Before. Will That Help Or Hurt With Voters?

• Rick Blangiardi: This Former TV Exec Wants To Be CEO Of Honolulu