WASHINGTON — In the past few months, President Donald Trump has invited supporters wearing “Make America Great Again” campaign gear onstage with him during official presidential speeches. He has criticized Democratic rival Joe Biden in Rose Garden addresses. He has played campaign-style videos in the White House briefing room, and he has used his campaign playlist, typically reserved for rallies, at official presidential events.

Presidents running for re-election have traditionally worked to balance official government business with campaign activity. But government watchdogs and officials from past administrations warn that Trump has smashed that norm, showing an unusual willingness to use his presidential platform for political purposes.

Trump’s penchant for blurring the lines between his campaign and his official duties came to a head last week when he confirmed that he was considering giving his acceptance speech for the Republican presidential nomination — one of the most anticipated moments of the election season — from the White House South Lawn.

“I’ll probably do mine live from the White House,” Trump said on Fox News. “The easiest, least expensive and, I think, very beautiful [location] would be live from the White House.”

Presidential ethics veterans said the savings weren’t his to take. “What Trump is doing is a form of stealing,” said Norm Eisen, who was President Barack Obama’s special counsel and special assistant for ethics and government reform.

“The taxpayer entrusts funds to the government to do the official business of the government. If they want to support a political candidate, they make a political contribution,” he said. “For Trump to effectively be reaching into all of our pockets to subsidize his proposed activity on the South Lawn … no, the taxpayer should not have to pay for that.”

Trump’s boundary stretching goes beyond the location of his acceptance speech, Eisen and others said.

The president has increasingly turned official White House events, both in Washington and on the road, into political events as the coronavirus pandemic has kept him off the usual campaign trail and unable to hold large in-person rallies.

Since March, Trump has taken official presidential trips to Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Georgia, North Carolina and Ohio. He has also made multiple visits to Arizona, Texas and Florida. All of those states are critical to Trump’s re-election.

“It’s always been a fine line that presidents ride with making sure that the official activity in an election year does not go too far into campaign activity,” said Kedric Payne, general counsel and senior director of ethics at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonprofit advocacy group. Trump, Payne said, is “barely disguising it as official activity.”

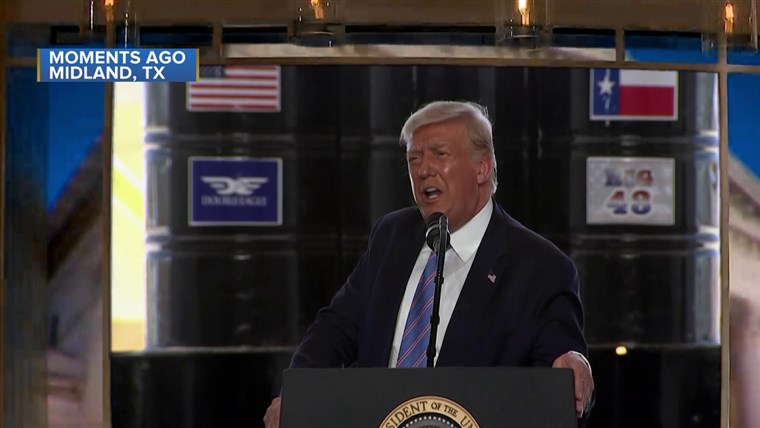

On an official government trip to Texas in July, for example, a senior administration official told NBC News that the visit was intended to highlight Trump’s energy policy and contrast it with that of Biden’s. On another official White House trip in June, to Arizona, the president headlined an event hosted by Students for Trump at a Phoenix church.

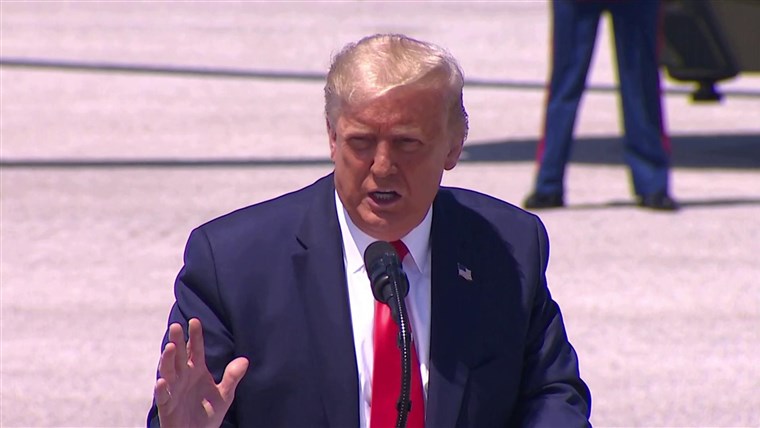

On his most recent presidential trip last week, to Ohio, the White House said Trump was met on Air Force One by a campaign senior adviser in the state, Bob Paduchik. The president held a small campaign-style rally on the tarmac and then visited a Whirlpool factory, where he made fun of Biden (“Did you ever watch Biden, where he’s always saying the wrong state?”). He rounded out the journey with a supporters roundtable and a campaign fundraiser.

The trips can become expensive when the airfare and the cost of federally mandated Secret Service protection are taken into consideration.

When a presidential trip involves both official and political events, the White House is supposed to use a formula to determine the amount of money that the campaign or the party should reimburse to the Treasury Department to protect taxpayers from paying for any political activities. The formula generally is not made public.

A spokesperson for the Federal Election Commission said that to distinguish political travel from official travel, the White House should consider the purposes and the natures of the events at each stop.

According to FEC data, the Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee have reimbursed more than $600,000 to the Treasury since May for airfare. Neither the Trump campaign nor the RNC provided NBC News with a breakdown of which trips taxpayers were reimbursed for.

Trump has also officially hosted a number of constituent-based events at the White House since the pandemic hit, involving truck drivers, farmers, veterans and seniors — a key voting bloc whose support for the president has slipped amid the pandemic. Five of the nearly two dozen events have been with faith leaders, a demographic that propelled Trump to victory in 2016 but whose support this time around has softened.

The campaign has pushed back against criticism that the president is misusing White House events.

“Democrats and the media are desperate to muzzle President Trump. They don’t want him tweeting, they don’t want him holding rallies, they don’t want him speaking at Mount Rushmore, and now they don’t want him holding press conferences,” said Tim Murtaugh, the campaign’s communications director. “Every week, Joe Biden reads speeches off the teleprompter attacking the president and the media gleefully reports every word, and President Trump is entitled to fight back.”

While there are some clear rules governing what sort of political activity the president can engage in on official trips and on the White House grounds (he cannot make fundraising calls from the Oval Office, for example), many of the president’s political actions are guided by tradition and norms.

The Hatch Act, a law limiting the political activities that federal employees can engage in to ensure that federal policies are carried out in a nonpartisan fashion and to protect federal workers from political coercion, does not apply to the president. Because of that, White House spokesman Judd Deere argued, Trump “is free to engage in political activity wherever he chooses.”

Officials from previous administrations say decoupling the political from the policy can be difficult, and many relied on White House lawyers, advisers and watchdogs to avoid Hatch Act and ethics violations.

“They were afraid of losing Congress, so they pushed the envelope on a bunch of things,” said Richard Painter, a Trump critic who was the chief White House ethics lawyer for President George W. Bush, recalling the 2006 midterm elections, when he frequently had to push back on some actions by administration officials.

Still, said Greg Jenkins, who was Bush’s deputy assistant and director of White House advance, “we had a policy that drew a bright line between official and political events.”

“All White Houses do events at the White House that advocate or oppose particular policies or proposals. While those are done for political purposes — to persuade people to your side — they weren’t electioneering,” Jenkins said.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

Johanna Maska, Obama’s White House director of press advance from 2009 to 2015, said she and other officials would get regular Hatch Act and ethics training from the White House counsel.

Maska said she recalled discussions during the 2012 campaign about whether using Obama’s official armored podium with the presidential seal at political events was an example of undue influence and a burden on taxpayers. Ultimately, the campaign decided to buy its own armored podium for Obama to use at events, which, Maska recalled, was expensive.

“Our typical default was we wanted to pay for everything to make sure we were following the law and weren’t making any in-kind contributions,” Maska said.

Eisen, the special counsel to Obama, said establishing a strict set of rules on the use of Air Force One and reimbursements, among other ethics issues, was a “huge priority” for the administration. “I personally trained everyone in the White House on these rules so they wouldn’t break them,” he said.

Eisen recalled telling Pete Rouse, a senior adviser to Obama who is an avid Grateful Dead fan, that he had to take down an Obama poster hanging in his office signed by the band because “there can be no taint of politics in this workplace, which is for policy.”

Government watchdogs say Trump has strayed far from the ethics norms of past administrations. They say he sets a dangerous precedent that could erode public trust.

“There are all sorts of debates, and the thing I was proud about is that our counsel would challenge us to make sure we were making the best decision for the taxpayers,” Maska said. “My question is: What is this counsel doing?”