DES MOINES — The first signs of trouble came early.

As the smartphone app for reporting the results of the Iowa Democratic caucuses began failing last Monday night, party officials instructed precinct leaders to move to Plan B: calling the results into caucus headquarters, where dozens of volunteers would enter the figures into a secure system.

But when many of those volunteers tried to log on to their computers, they made an unsettling discovery. They needed smartphones to retrieve a code, but they had been told not to bring their phones into the “boiler room” in Des Moines.

As a torrent of results were phoned in from school gymnasiums, union halls and the myriad other gathering places that made the Iowa caucuses a world-famous model of democracy, it soon became clear that the whole process was melting down.

Volunteers resorted to passing around a spare iPad to log into the system. Melissa Watson, the state party’s chief financial officer, who was in charge of the boiler room, did not know how to operate a Google spreadsheet application used to input data, Democratic officials later acknowledged.

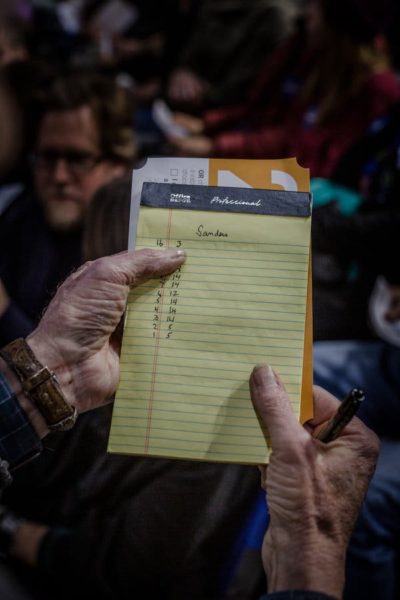

Others, desperate to verify results, began telling some precinct leaders to email photographs of their worksheets — the paper forms used to tally results — to a dedicated email address. But for hours, no one monitored the inbox. When it was finally opened Tuesday morning, there were 700 unread emails waiting, with photos that had been sent sideways; volunteers had to crane their necks to decipher the handwritten forms.

An hour after the caucuses began, the Iowa Democratic Party chairman, Troy Price, huddled in another room with other officials, none of them with a clear strategy to manage the unfolding chaos or answers to share with increasingly exasperated presidential campaigns. A conference call with the campaigns ended with Mr. Price hanging up on them, amid accusations that caucus results in Iowa may have been incorrectly reported for decades.

As disastrous as the 2020 Iowa caucuses have appeared to the public, the failure runs deeper and wider than has previously been known, according to dozens of interviews with those involved. It was a total system breakdown that casts doubt on how a critical contest on the American political calendar has been managed for years.

Until now, the main public villain in the Iowa caucus fiasco has been the reporting app, created by a company called Shadow Inc., along with a “coding issue” in a back-end results reporting system that state party officials blamed for the chaos. But the crackup resulted from cascading failures going back months.

The fragile edifice of the caucuses, which demoralized Democrats in search of a strong nominee to take on President Trump, crumbled under the weight of technology flops, lapses in planning, failed oversight by party officials, poor training, and a breakdown in communication between paid party leaders and volunteers out in the field, who had devoted themselves for months to the nation’s first nominating contest.

The wider scope of the malfunctions came to light partly because of a new set of reporting requirements, mandated by the Democratic National Committee after allies of Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont pushed the national party to demand more transparency following his narrow loss to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Iowa caucuses.

The widespread lack of faith in the Iowa results has shaken many Americans’ confidence in their electoral system. Mr. Trump has reveled in the meltdown. Democrats have proposed abolishing caucuses and ending Iowa’s time at the front of the presidential nominating calendar.

Even as party officials scramble to contain the fallout, the full extent of the problems in Iowa is still not known.

An analysis by The New York Times revealed inconsistencies in the reported data for at least one in six of the state’s precincts. Those errors occurred at every stage of the tabulation process: in recording votes, in calculating and awarding delegates, and in entering the data into the state party’s database. Hundreds of state delegate equivalents, the metric the party uses to determine delegates for the national convention, were at stake in these precincts.

The Iowa Democratic Party released a list of 92 precincts on Sunday that it said were flagged as problematic by three presidential candidates — Mr. Sanders; Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind.; and Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. That figure is far fewer than the number with inconsistencies captured in the Times review. The Associated Press said it was unable to declare a caucus winner.

Sean Bagniewski, the Democratic chairman of Polk County, which includes Des Moines, blamed state officials for neglecting the hard work of overseeing the caucuses.

“It’s very easy to slip into the celebrity of the caucuses,” Mr. Bagniewski said. State party leaders, he said, were distracted by offers to appear on cable TV, hobnob with national Democratic leaders and meet presidential candidates, and did not take their day-to-day duties “seriously from the get-go.’’

In the aftermath of the disaster, state and national party leaders are pointing fingers at one another. On Sunday, Mr. Price, the state party chairman, said he was proud of the volunteers who put on the caucuses and that the state party worked with the national committee for months to prepare for them.

“We are conducting a thorough independent review of the process, and it would be irresponsible for us to rush to judgment before that review is complete,” he said in a statement.

Tom Perez, the chairman of the national committee, placed blame directly on the Iowa Democratic Party and Mr. Price.

“Troy Price was doing his best, but it wasn’t enough,” Mr. Perez said in an interview with The Times on Sunday, noting that while the national and state parties work in partnership, the Iowa Democratic Party is ultimately responsible for administering its own nominating contest.

The D.N.C. approved Iowa’s delegate selection plan, but left the state party to determine on its own how to collect and tabulate caucus results, Mr. Perez said, adding that the national party did not test the state’s app or set standards for training or preparation.

Mr. Perez said he was not responsible for what state parties and their leaders do.

“I do not conduct a performance evaluation of every party chair,” he said.

Asked whether the D.N.C. would increase its scrutiny of other caucuses run by state parties, including Nevada’s in less than two weeks, Mr. Perez said he would “implement all of the lessons learned,” but did not specify how.

Some of the roots of the Iowa debacle stretch to 2016, when Mr. Sanders finished a fraction of a percentage point behind Mrs. Clinton in the state’s caucuses. He and his allies were furious.

Their caucus-night data indicated he had won the popular vote, but there was no way to prove their case. Precincts only reported how many delegates should be allotted, without the underlying vote totals. And there was no mechanism for Iowa Democrats to recount caucus results, because the state party did not maintain paper records of them.

In 2017, the D.N.C. formed a commission to propose changes to the party’s presidential nominating system, including the way caucus results are reported.

The Iowa Democratic Party tried to comply with the national committee’s orders, which were enacted in 2018, but the two organizations sparred over how the state should address the new requirements and what role the national party should play in Iowa Democrats’ affairs.

Since the disaster Monday night, the D.N.C. has said it took a hands-off approach to the entire operation. But an email from the summer, obtained by The Times, indicates that the national committee tried to involve itself in preparing for the caucuses — in particular, with security.

In July, according to the email, Kat Atwater, the D.N.C.’s deputy chief technology officer, proposed language for vendor contracts that would give the national party access to source code, and allow it to test apps and other products used by the state party.

Iowa party officials rejected the proposed language.

Weeks later, in August, the national party cited security concerns when it vetoed the Iowa Democratic Party’s proposal to hold a “virtual caucus,” which would have allowed absentee participation by phone.

The disagreements delayed approval of Iowa’s caucus plan until late September. The state would use remote “satellite caucuses” to allow Iowans who could not make it to their precinct caucus sites to participate, and a smartphone app for precinct leaders to report results.

One man would oversee all of it.

Mr. Price, 39, a lifelong Iowan who became chairman of the state Democratic Party in July 2017, had a sterling resume. He had been an aide to two former Iowa governors and a top figure in both President Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign in the state and in Mrs. Clinton’s 2016 run.

He relished the national attention the caucuses attracted. In early November, at an annual state party dinner that drew 13,000 people, he spoke for 18 minutes, longer than any of the presidential candidates did.

Mr. Price spent the months before the caucuses defending Iowa’s pre-eminent position in the presidential primary process, as candidates bemoaned Iowa’s lack of diversity and arcane caucusing process.

At an August news conference, Mr. Price projected total confidence.

“Just know this,” he said, gesturing with a pointed finger for emphasis. “On Feb. 3 of 2020, caucuses will take place in this state. We will be first. And they will be, without a doubt, the most successful caucuses in our party’s history.”

Just days before the caucuses, precinct leaders received their first instructions for downloading an app they were to use to record and send results.

The app was created by Shadow Inc., a company recommended to Iowa party officials by Democratic leaders in Nevada, who were working with it as well.

The chief executive of Shadow, Gerard Niemira, was a veteran of the 2016 Hillary Clinton campaign, where he oversaw tech products like an app the campaign used to take advantage of the quirky math of caucuses and track results in real time.

Because of the delays in planning Iowa’s caucuses, Shadow personnel didn’t enter into a contract for the Iowa app until the fall of 2019, compressing an already tight timeline on a deal that paid relatively little — a bit more than $60,000 so far — for customized technology services.

In November, Iowa officials gathered in Des Moines with Harvard election security experts including Robby Mook, Mrs. Clinton’s 2016 campaign manager, to test processes involved in the caucuses. But the app wasn’t part of the exercise.

Still, Shadow developed an initial version of the app that month and began testing and updating it, according to a person involved in the effort. As the caucus date approached, more updates came, but the developers didn’t regard them as critical.

The weekend before the caucuses, officials from Shadow, the state party and the D.N.C. gathered to run final tests. They fed in false data to verify that the quality-control system would catch anything amiss. The app worked well, according to a person involved. But no evidence arose of a bug that would jumble a portion of the results on caucus night.

The Sunday before the caucuses, Mr. Price kept up a busy schedule. He taped an interview with Kasie Hunt of MSNBC in the early afternoon. He posed for a photo on the Fox News set with Donna Brazile, a former chairwoman of the Democratic National Committee. In the evening, he was at a Super Bowl party with Senator Amy Klobuchar.

Yet in Polk County, where Democrats were preparing for 177 precinct caucuses, it had already been clear all week that the app had problems.

When precinct chairs reported issues, the state party referred them to a lone help-desk employee, who did not always respond to calls and emails.

Six hours before the caucuses were to start at 7 p.m. Monday, precinct leaders received a final email about the app with an ominous instruction: “If the app stalls/freezes/locks up: Close out of the app and log back in with your PIN. The app should save where you were. If it does not, please call in your results.”

Most precinct caucuses ran smoothly across the state. But when some precinct leaders tried to report the results, the app sometimes froze. Calls to the state party hotline sometimes languished on hold for five hours.

To relieve pressure on the state party, D.N.C. officials executed a contingency plan created for natural disasters or terror events: using a backup call center at the party’s headquarters on South Capitol Street in Washington, where about 40 people began taking calls.

By then, it was clear that a catastrophe was taking place at the Iowa Events Center, a venue for auto shows and state wrestling tournaments that was serving as caucus central.

The state party’s phones were jammed. Users on the website 4chan had publicly posted the election hotline number and encouraged one another to “clog the lines.” The party’s volunteer phone operators also had to deflect calls from television news reporters in search of caucus results that were hours overdue.

One floor below, representatives from the seven presidential campaigns competing in Iowa waited in a room with no windows, no food, no water and no information. They took turns trying to call state party officials in search of information.

On a conference call with the campaigns later that night, Mr. Price struggled to explain the information blackout. He said the problems stemmed from party officials having to collect three sets of data from all precincts for the first time.

“You always had to calculate these numbers, all we’re asking is that you report them for the first time,” Jeff Weaver, Mr. Sanders’s closest adviser, said he told Mr. Price on the call. “If you haven’t been calculating these numbers all along, it’s been a fraud for 100 years.”

Mr. Price ended the call.

As engineers scrambled to repair the app, panicked Iowa party leaders were making a choice. It was time, they decided, to abandon digital methods and rely on the old ways, gathering data over the phone and doing the math by hand — a decision that would open a whole new can of worms.

Each precinct leader had 36 separate figures to report, along with two separate six-digit verification numbers — and there were more than 1,700 precincts, including the satellites.

In the chaos, caucus results collected by phone operators were riddled with errors. Dozens of the volunteers returned over the next three days to crosscheck them and input results from caucus worksheets that came in by email or through the app. One was delivered days later by the Postal Service.

In the Times review of the data, at least 10 percent of precincts appeared to have improperly allocated their delegates, based on reported vote totals. In some cases, precincts awarded more delegates than they had to give; in others, they awarded fewer. More than two dozen precincts appeared to give delegates to candidates who did not qualify as viable under the caucus rules.

Given the slim lead Mr. Buttigieg now holds over Mr. Sanders in state delegate equivalents, a full accounting of these inconsistencies could alter the outcome. But without access to the precinct worksheets, it is difficult to determine whom the errors hurt or favored.

As caucus night gave way to a week of finger-pointing, some local Democratic volunteers expressed anger at what they saw as efforts by national party officials to blame Iowa for the mess.

“The D.N.C.’s kind of hanging us out to dry,” said Steve Drahozal, the Democratic chairman in Dubuque County. “Instead of saying ‘Good job!’ to the local volunteers, they’re disrespecting a lot of grass-roots organizing that was done. There are criticisms they can make, but this was an extremely smooth, well-organized caucus. We just couldn’t get the data reported.”

Reid J. Epstein and Sydney Ember reported from Des Moines and Manchester, N.H., and Trip Gabriel and Mike Baker from Des Moines. Reporting was contributed by Michael Wines and Jack Healy from Des Moines, Shane Goldmacher from Manchester, and Keith Collins, Denise Lu, Charlie Smart, Steven Moity and Pierre-Antoine Louis from New York. Jack Begg, Susan Beachy and Alain Delaqueriere contributed research.

-

- The first-in-the-nation primary is underway as New Hampshire’s voters weigh in on an unsettled Democratic field. Follow the latest updates.

-

- Polls begin closing at 7 p.m., and the New Hampshire secretary of state has said final results could arrive as early as 9:30 p.m. Track the results.

-

- There are 24 delegates up for grabs in New Hampshire, but the vast majority are awarded after February. Here’s the primary calendar.

-

- Learn more about the Democratic presidential contenders.

Michael Bennet

Joe Biden

Michael R. Bloomberg

Pete Buttigieg

Tulsi Gabbard

Amy Klobuchar

Deval Patrick

Bernie Sanders

Tom Steyer

Elizabeth Warren

Andrew Yang

-