It’s almost budget time again, with all its rituals and hoopla. For many Australians, it might be the only time they really focus on politics in the year.

“I know people think budgets are pretty dry things,” former treasurer and prime minister Paul Keating said in a post-budget address in 1995. “I suppose they are, but they do get your blood racing on occasions.”

But what is the budget trying to do? Why does it matter, and whose blood gets racing when it goes right – or spectacularly wrong?

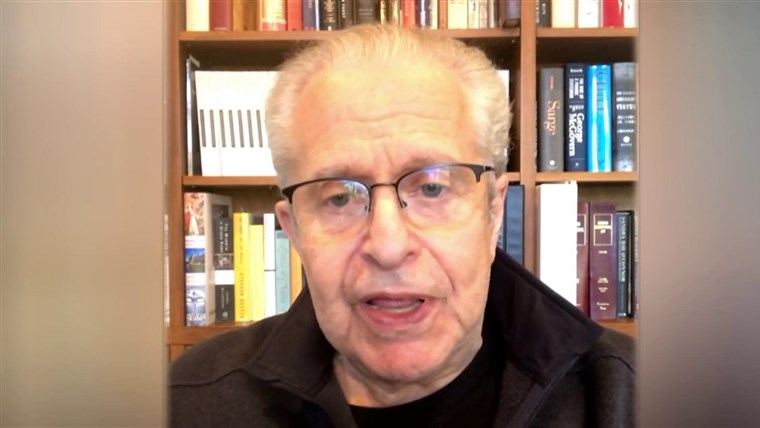

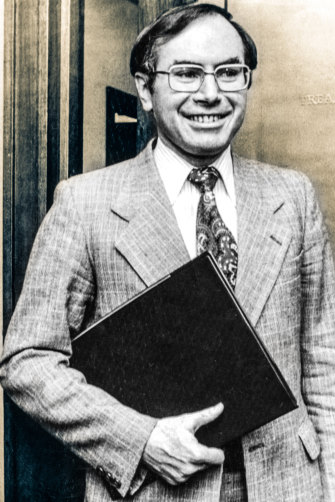

Paul Keating said his 1988 budget was the pay-off for tough economic reforms.Credit:Image design: Steve Kiprillis

What is the federal budget?

At its most basic, the budget is the government’s chance to set out its policy priorities each year. Parties make promises at elections and the budget sets out how they will spend money to make those things happen – plus other things not even imagined during the election campaign – and the ways they will raise the money to pay for it all.

The budget papers detail new expense and revenue measures, along with the forecast state of the economy over the next four financial years (known as the forward estimates). This includes estimates of how fast the economy will grow, the unemployment rate, how much tax and other revenue will be collected, and how much is planned to be spent on programs and capital works.

But the budget is also theatre. It’s the biggest political set piece each year, and the biggest event in the parliamentary calendar. Budget night is the treasurer’s chance to shine without the prime minister getting in his way (treasurers have all been men so far).

There’s a ritual to the events surrounding the evening: footage of the treasurer hard at work in his office in the Treasury building down the hill from Parliament House; photos of the budget papers being printed; more photos of the treasurer arriving at work in the wee hours of budget day, then re-arriving at an “impromptu” press conference at a slightly more sensible hour.

In the social media age, another ritual is keeping watch on the Parliament House “budget tree”, a red maple in a courtyard that usually turns a brilliant crimson just in time for the autumn budget sittings.

When this tree turns red at Parliament House, it’s budget time – at least, traditionally. Here, minister Jenny Macklin talks with treasurer Wayne Swan in May 2011. Credit:Alex Ellinghausen; image altered

Paul Keating pioneered the mid-afternoon lock-up press conference – facing questions from reporters after they have had an initial chance to go through the budget papers. The tradition has been kept ever since, giving the treasurer of the day the opportunity to wander among the scribes and make his pitch.

The treasurer’s budget speech to Parliament is broadcast live (Keating also pioneered this, with the first televised address in 1984, a week after the closing ceremony of the Los Angeles Olympic Games), followed by a series of televised post-budget interviews.

The next day, the sell begins.

No media outlet’s microphone can hide from the prime minister and treasurer, who go into overdrive spruiking the budget and all their plans for the next year or four.

The budget also functions as a political opportunity, with the government holding party fundraising events on budget night and in the aftermath. The opposition party does the same after its leader’s “budget in reply” speech two days later.

Peter Costello’s baby bonus came with this advice in 2004.Credit:

Is it like my household budget?

Not really. For starters, it’s worth $500 billion. And governments have the ability to raise taxes and sell debt. If you wanted to start up a new spending program, say, to plant vegetables in your backyard, you couldn’t go around taxing your neighbours to get the money to do that – you would have to fund it yourself.Conservative governments, in particular, talk a lot about living within their means, but the fact remains they could still raise taxes or put in new ones if they had to.

The government can use its budget to try to affect the way individual households behave, for the good of the economy.

It’s also vital that governments consider the whole economic picture when making their budgets – also known as macro-economics. If your attempt to tax your neighbours was unsuccessful, you might decide to put aside the money you would normally spend at restaurants to eventually pay for the new veggie patch.

When you increase your savings, that’s a matter within your own four walls. But if every household decides to increase their savings at the same time, that’s a problem for the government because it affects the whole economy – economists call this the “paradox of thrift”. The government can use its budget to try to affect the way individual households behave, for the good of the economy.

Finally, if your household can’t repay its debts, creditors can take you to court, but it’s pretty hard for a country to become bankrupt. Governments can issue more debt with super-low interest rates if they run into financial trouble. Your household would have the keys to your house – and your new veggie patch – taken away if you didn’t pay back the bank.

Is the budget just a policy launch on steroids?

The budget also has a technical legal reason for existence: the government has to pass legislation in order to keep its authority to continue spending money. These laws are known as the appropriations bills and, under parliamentary procedure, the treasurer’s budget speech introduces them.The opposition leader’s speech, two days later, formally starts off debate on the bills.

The appropriation bills are what gives the government its “supply” – the money vital to keeping government running. It covers the “ordinary annual services” such as funding for departments to cover salaries and office rents, amounting to about 20 per cent of all spending. If a government can’t secure supply, it no longer has the confidence of the Parliament and by convention the prime minister has to resign.

George Turner preparing Australia’s first federal budget in 1901.Credit:Fairfax Media

The rest of the money the Commonwealth spends is authorised via other, permanent legislation, such as for pensions and other welfare payments.

Australia’s first budget named the 152 public servants paid by the Commonwealth (although, as the Federation found its feet, there was a significant number called “Appointment not made”). Today that would be tricky: there are more than 242,000 federal public servants.

Most of the Commonwealth’s revenue in that 1901 budget came from customs and tariffs, but most of this went straight back to the states. Premiers agreed to the Commonwealth taking over the power to levy tariffs only in exchange for a constitutional guarantee they would receive three-quarters of the revenues for the first decade of Federation. This was known as the Braddon Blot, after Tasmanian leader Edward Braddon, who was especially insistent on the measure.

These days about one-eighth of budget spending is GST revenue transferred to the states. The biggest-ticket item is social services, costing more than a third of the government’s $500 billion, with more than $50 billion a year on the age pension alone.

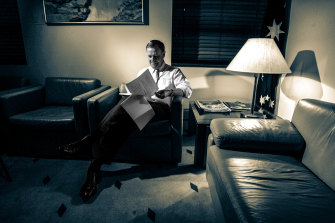

Treasurer Peter Costello looks over his twelfth budget late into the night before Budget Day in 2007. Credit:Andrew Taylor

When is the budget?

Over the past couple of decades, budget day has, by convention, been the second Tuesday in May.

The first Commonwealth budget was delivered in October – 10 months after the Federation formed in 1901 – and its finalisation largely fell on treasurer George Turner’s shoulders alone, as his departmental secretary was ill for the five weeks prior.

For quite some time, no fixed date was set for the budget and it meandered around the calendar between July and September. Governments viewed it a bit like being able to set their own timing for an election and the date was a closely held secret.

As prime minister, Keating brought it forward to May in 1994 so the economic statement could be handed down and the associated legislation passed before the July 1 start of the financial year to which it applied. This move was in line with what other countries were doing, such as Britain, which moved its budget to March for an April start to the fiscal year.

While that seems sensible enough, the date isn’t fixed by law, only convention. That means it can still be moved as suits a government’s political purposes. Peter Costello delivered his first budget in August 1996 because the election had been held in March. And in the past two election cycles, the budget was brought forward to accommodate prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison’s preferred poll timetables – held a week earlier than usual in 2016 and a month early in April 2019.

In 2020, the sheer scale of the economic uncertainty brought about by the coronavirus led Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg to delay the budget until October.

The states usually hold their budgets as soon as possible after the federal one. Many used to have them before the Commonwealth revealed its plans, but after years of having to rejig their numbers because of unexpected changes in GST revenue, they have shifted to go shortly afterwards. Another factor is that substantial federal policy shifts can affect the states’ bottom lines.

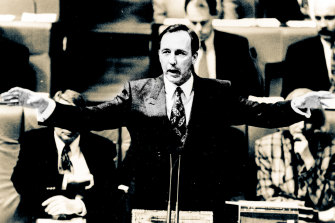

Paul Keating during the budget session question time in 1992.Credit:Peter Morris

So it’s just about the one big speech?

While all the focus is on budget day, months of work goes into pulling the plan together. That said, Bill Hayden put together his first and only budget, in 1975, in just 74 days.

The process usually starts in September. The cabinet decides the rough parameters and timing of the budget, then calls for submissions. Hundreds of submissions for what government should do with the nation’s money pour into Treasury’s inbox.Departments, via their ministers, as well as stakeholders and special interest groups, and even individual Australians, put in their two cents.

For example, among the 330 published submissions to the 2017-18 budget is one from a woman who introduces herself as “a Buddhist and a member of the electoral district of Newtown” and goes on to ask for more money to be spent on supporting Indigenous people, LGBTI and gender equality, foreign aid and the environment, while stopping offshore immigration detention. Another individual puts in a two-paragraph submission asking for the small business instant asset write-off to be made permanent to help Uber drivers.

As the government grapples with the coronavirus-induced recession, no one expects to be able to “balance the books” given the huge spending needed and the wipeout in revenue.

Once all of these suggestions are sorted through, government departments prepare “portfolio budget submissions” for the cabinet. This is a fancy way of saying they put together a list of proposals for things they would like to spend money on, and potential savings.

The Coalition government since 2014 has had a “budget repair” strategy requiring ministers to offset all new plans to spend money with savings. It had campaigned heavily on the so-called budget emergency after Labor took the books into deficit to keep Australia afloat during the global financial crisis. However, Frydenberg has cast aside that approach as the government grapples with the coronavirus-induced recession, because no one expects to be able to “balance the books” given the huge spending needed and the wipeout in revenue.

Treasurer John Howard leaves his office at Parliament House in 1979. Credit:Fairfax Media

Who does all the maths?

The detail of what makes it into the budget is refined by the expenditure review committee (ERC), a sub-committee of the cabinet, set up by Hayden in 1975. It usually comprises a core group of ministers with others rotating in as their proposals are considered. Under previous governments, the ERC has been led by the treasurer but, at the moment, Morrison chairs it with Frydenberg as his deputy. Finance Minister Mathias Cormann, Deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack, Health Minister Greg Hunt and Social Services Minister Anne Ruston are also members.

During John Howard’s time as treasurer in the late 1970s and early 80s it became known as the “razor gang”, amid a fierce search for cuts, and the nickname has stuck.

The treasurer sets up in the “budget war room”, a secure office where he can discuss plans with officials and be sure nothing leaks.

Working through the details of how new programs will actually work means a lot of long days and late nights, especially for Treasury staff.Treasury and Finance check and recheck all the maths involved; no one wants to be responsible for the dreaded “budget black hole”.

In these final weeks, the treasurer sets up in the “budget war room”, a secure office in the Treasury where plans can be discussed with officials without fear of leaks.

Eventually, the whole thing has to be signed off by the full cabinet. The major initiatives have to be set at least two weeks before budget day, because changes require the Treasury to redo all its macro-economic calculations and forecasts. The communications plan and messaging around the budget need time to get all the sign-offs required – no easy task when there are multiple ministers and departments involved. However, some minor last-minute tweaks may be made as the budget books usually don’t go to the printer until a couple of days before they are presented.

The Minister for Finance and the Public Service, Mathias Cormann, and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg during the budget lockup at Parliament House in Canberra in 2019.Credit:Alex Ellinghausen; image altered

What is the lock-up all about?

Budget lock-ups are what they sound like – people are locked in a room with the budget papers, sandwiches and old-school calculators (reporters have to surrender their phones and smart watches) ahead of their formal release. Media are in the main lock-up of typically more than 500 journalists in Parliament House, where the treasurer holds a press conference and his department’s officials are available to answer questions about the detail of the various measures – access rarely given to media. There are also separate events for selected interest groups and opposition MPs.

Ben Chifley started the lock-up almost by accident to give the newspapers time to file for their morning editions.

The treasurer’s speech is traditionally at 7.30pm, well after the local financial markets are closed, because what the government does can have major impacts. That same market sensitivity is the reason for the strict confidentiality arrangements around the budget information. However, other countries, such as Canada and New Zealand, hold their budget lock-ups earlier in the day.

Ben Chifley, who was both prime minister and treasurer during the 1940s, started the lock-up almost by accident to give the newspapers time to file for their morning editions. John Kerin is the only treasurer to have abandoned the practice since, in 1991, and delivering an afternoon budget. He argued it was anachronistic to stick to the later time in the age of 24-hour global financial markets. It was the only budget he delivered.

The media lock-up usually goes for about six hours, from lunchtime until the treasurer stands up in Parliament to make his speech. No communications are allowed out; reporters sign a declaration they will stick to the embargo or risk fines or even jail time.

In modern politics, governments carefully choreograph the announcement of key measures in the lead-up to the budget via formal statements and sometimes well-placed leaks. In some years, so much of the budget is known in advance that people query the need for the lock-up at all. However, the OECD says the arrangement “has served to promote more informed reporting and commentary on the budget”. It gives reporters time to digest the budget figures in a detailed way not often afforded for policy announcements in the 24-7 news cycle.

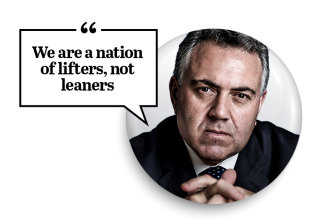

Joe Hockey in 2014.Credit:

What are some notable budget moments?

Budgets can be make-or-break moments politically, but Arthur Fadden’s 1941 budget, delivered when he was treasurer and prime minister, was the last to force a change of government. The opposition, led by John Curtin, moved to reduce the budget by one pound and convinced the independent MPs to side with him, thus leading the House to reject the government’s plans in an effective vote of no confidence. Curtin was sworn in as prime minister four days after the vote.

The supply crisis in 1975 that led to Gough Whitlam’s dismissal didn’t involve Parliament formally rejecting the budget – the Senate only delayed its consideration of the appropriation bills.

In his second stint as treasurer, under the revived Menzies government, Fadden came up with the idea for a wool tax in the middle of the night and wrote it down on the only thing he could find at the time: toilet paper. It was included in the 1950 budget but was highly unpopular and was repealed the following year.

Howard’s time as treasurer produced two moments that endure in popular memory. In 1979, his broken promise to end a short-term tax levy led the Illawarra Mercury to scream on its post-budget front page, “Lies, Lies, Lies!” The headline was much used by the Labor opposition during debates in the aftermath.

The following year, journalist Laurie Oakes was leaked the entire budget before its delivery. He spoke about the infamous moment on his retirement in 2017, revealing a contact had handed him Howard’s budget speech in a car park and given him 15 minutes to “gabble the whole lot into a tape recorder”.

The orthodox view is that post-election budgets can be harsher than pre-election ones because there is still time for the voters to forgive you. It’s not always the case.

The theatre around budgets in modern politics means they often become remembered by a single phrase from the treasurer. Keating’s triumphant 1988 budget – the first delivered in the new Parliament House and boasting a healthy surplus – is remembered for his declaration it was “bringing home the bacon” after years of tough economic reforms. And who could forget Costello introducing the baby bonus in 2004 and urging people to “have one for mum, one for dad and one for the country”?

The orthodox view is that post-election budgets can be harsher than pre-election ones because there is still time for the voters to forgive you. It’s not always the case, as the 1993 and 2014 budgets show.

The 1993 one, composed by John Dawkins after Keating won the “unwinnable” election, failed to deliver all of the promised “L-A-W law” tax cuts (they had pledged two sets of cuts and included just one). And Joe Hockey’s 2014 “lifters and leaners” budget broke almost every element of Tony Abbott’s election-eve promises about not cutting funding. Its harshness was compounded in public minds by footage that emerged of Hockey and Cormann smoking cigars outside the Treasury building in the lead-up.

Get our Morning & Evening Edition newsletters

The most important news, analysis and insights delivered to your inbox at the start and end of each day. Sign up to The Sydney Morning Herald’s newsletter here and The Age’s newsletter here.