In 1918, four women with ties to UC Berkeley broke through the glass ceiling that had blocked women from being elected to the California Assembly. From left: Grace Dorris, Elizabeth Hughes, Anna Saylor and Esto Broughton. (Photo courtesy of Hon. Sunny Mojonnier/Women in California Politics. Copying or reusing the photo without written permission is prohibited.)

It was a year of challenge and turmoil: an overseas war, a deadly pandemic, a damaging economic shock. The U.S. Congress was polarized and paralyzed. Across the nation, conflict flared over political rights and equality and led to protest leaders being arrested and jailed; some began hunger strikes.

The year was 1918, and the protesters were pressing for the right of women to vote. In California, women had won suffrage seven years earlier, and as that year’s election campaign unfolded, a number of local political races were focused on overcoming the barriers that had kept women from the state Legislature.

When the polls closed that Nov. 5, four women had won their contests. And as they prepared to take office as the first women ever to serve in the California Assembly, the reputation of the University of California’s Berkeley campus as a center of innovative political thinking and influence was reinforced up and down the state, and across much of the nation.

Esto Broughton, from Modesto, had graduated in 1915 and from the law school a year later. Grace Dorris, from Bakersfield, was a 1909 graduate, a teacher and an activist in the women’s suffrage movement. Elizabeth Hughes was a teacher in Oroville, and she taught art in UC Extension classes. Anna Saylor had brought her family from Indiana to live in Berkeley, planning for her children to attend the university; she became the president of Berkeley’s influential Twentieth Century Club for women.

Some of their opponents and some journalists at that historic moment didn’t quite know what to make of them, instead focusing on their diminutive size or cooking skills. But the four women, upon arriving at the state capital, quickly established their political influence and, in just a few years, had an impact on law and political culture that resonates today, as the UC on Oct. 3 celebrates the 150th anniversary of the Board of Regents’ 1870 decision to admit women students.

The four women in the Legislature’s Class of 1918 set a standard for high-impact engagement on important issues — social and economic, local and national. While the progress of women in the Legislature since then has been uneven — decades would pass before a Black woman was elected to the Legislature — the four continue to inspire today’s generation of Berkeley graduates who pursue political careers.

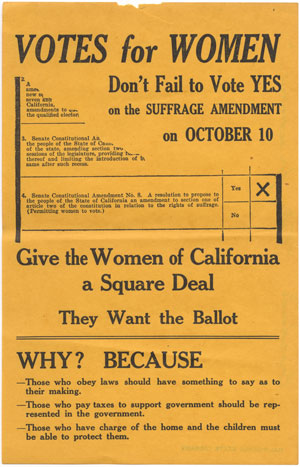

After decades of campaigning by suffragists, California’s men-only electorate in 1911 narrowly approved Senate Constitutional Amendment No. 8 — also known as Proposition 4 — which gave women the right to vote. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, Ca.)

“When you look back at California history, there were so many cultural disadvantages that women had in terms of going into politics,” said Steve Swatt, a Berkeley graduate who co-wrote Paving the Way: Women’s Struggle for Political Equality in California with his wife, historian Susie Swatt, and political communication experts Rebecca LaVally and Jeff Raimundo.

“They were able to overcome those obstacles through grit and determination and resilience,” he said. “They ran strong campaigns against men, which was unheard of at the time. They learned how to raise money. They learned how to build coalitions. They learned how to become politicians. … They were real pioneers and trailblazers.”

Regrettably, though, their accomplishments are not widely known, said Phyllis Gale, a board member of the Berkeley Historical Society who worked for 30 years at UC Berkeley and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “Each of these women stood up, took a chance and ran for a state office, and they won the first time they ran. They did important things. Today, we stand on their shoulders — but we don’t know it.”

Struggle, defeat — and then historic progress

The founding of the University of California in 1868 coincided with the emergence of the woman’s suffrage movement as a national force, and through the movement’s early victories and setbacks, Berkeley emerged as a center for its ideas and energy. The university evolved into California’s intellectual capital, and Berkeley was its fifth biggest city. As the number of women in the student body rose steadily into the early 20th century, UC graduates and students became vital to the drive for suffrage.

“Women came from all over the country,” Gale said. “The university was a magnet. Berkeley was a magnet. This is where they felt there was power.”

Women’s suffrage supporters met in San Francisco, apparently during the 1911 campaign that won California women the right to vote. The Bay Area — including UC Berkeley — was a focal point for state and national suffrage campaigns. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, Ca.)

In 1911, California’s voters — all of them men — narrowly approved a women’s suffrage referendum with 50.7% of the vote. Almost immediately, the pent-up political energy of women was released into the political arena.

But the onset of World War I transformed the political landscape. As the U.S. sent troops to battle, including 112,000 from California, the departure of men opened opportunities for women.

One of them was Dorris. Her husband, Bakersfield attorney Wiley Dorris, had planned to run for the California Assembly in the 1918 election. Instead, he went to war — and she decided to run in his place.

In all, 17 women ran for U.S. Congress and the state Legislature that year. For Dorris and Broughton, UC degrees “made them very credible candidates,” said Susie Swatt.

Clearly, the Legislature’s new class of women politicians was both a novelty and a powerful force, and Paving the Way describes how that put some men in unfamiliar territory.

Hughes’ opponent, in the days leading up to the election, admonished voters that politics “is no pink tea job,” and that it required “a virile man” who could withstand the punishment of the political process.

After the election, one newspaper account described Dorris as “frail and determined,” and another painted Saylor as “a quiet, earnest little woman.”

Broughton had suffered from spinal tuberculosis as a child, which left her with curvature of the spine and one leg shorter than the other. But at Berkeley, she was coxswain of the women’s Class of 1915 rowing team. She learned to ride a motorcycle, and she became a lawyer. And yet, one press account of her election victory noted that “folks at home are going to miss her raisin pies.”

Politicians with vision and lasting impact

In fact, each of the four victorious women were seasoned leaders, with bases of support in more than one political party. But, said Gale, they didn’t see themselves as leaders of a women’s movement.

“Looking back through the lens of the present time, you would think, ‘My God, they’re the first feminists,’” she said. “But they didn’t think of themselves that way. They saw themselves as civic leaders.”

In Victorian gender roles, women tended to focus on domestic issues — education and health, for example, but also rights and protections for women.

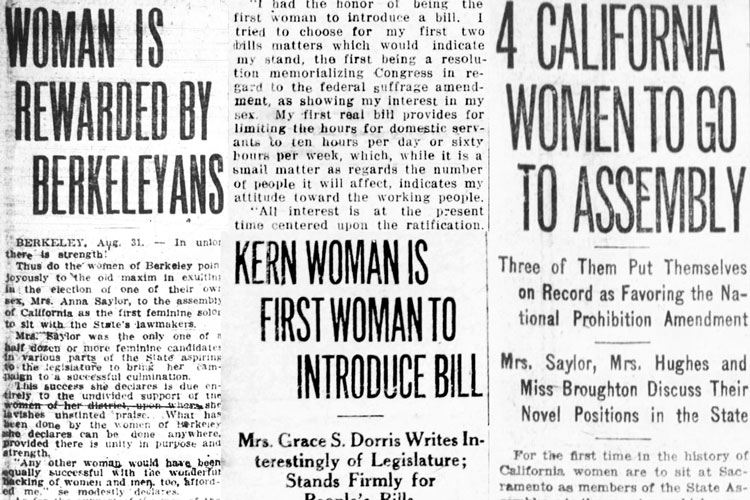

The election of the first four women to the California Assembly in 1918 generated extensive news coverage statewide, and beyond. While much of the coverage was serious and respectful, some reporters weren’t quite sure what to make of the new lawmakers. (Graphic by Hulda Nelson/UC Berkeley)

Women in the Legislature’s Class of 1918 “brought these problems that women couldn’t solve at home, by themselves, to the Legislature,” Gale said, “and began to introduce legislation to solve them.”

Saylor was a powerful advocate, working for measures to protect children in the workplace; improve juvenile justice and abolish the death penalty for minors; upgrade the treatment of imprisoned women; and create psychiatric units in prisons.

Hughes, a high school teacher, focused on education issues, including an expansion of Chico State Normal School, which eventually became California State University, Chico. She was named chair of the education committee after challenging a legislative practice of assigning committee leadership based on seniority.

Still, the new lawmakers were not limited to such civic issues. Broughton helped lead the Assembly’s effort to create community property rights for wives, but she also became its leading expert on irrigation policies that were essential to farm country.

Dorris’ first initiative after taking office in 1919 was a resolution in favor of the proposed 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which in 1920 gave women nationwide the right to vote, and she pressed for a maximum 60-hour work week for domestic servants. But she also campaigned against Kern County’s biggest landowners, insisting that they open their idle lands to food production and share water rights with local farmers.

After the revolution, slow progress

By 1927, all four of the pioneering women were out of office — some by choice, some by electoral defeat. That year, Saylor became the first woman ever to serve in a California governor’s cabinet when new Gov. C.C. Young, an 1892 UC graduate, named her the director of the Department of Social Welfare.

And yet, after the seeming revolution of 1918, progress for women politicians slowed considerably.

Mae Ella Nolan of San Francisco, was the first California woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, succeeding her husband in 1921 after he died in office and serving almost two terms. Florence Prag Kahn, an 1887 UC graduate, was elected to the House after her husband died in 1927 and served five full terms. She was the second California woman, and the first Jewish woman, to serve in Congress.

Over the next half-century, only 10 other women were elected to the California Legislature. Not until 1976 was a woman elected to the state Senate. U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Oakland) noted that it took decades for Black women to be elected to the Legislature — and added that, as a Berkeley alumna, she is “proud” that two other UC graduates again played historic roles.

“We can’t forget that it took almost another 50 years for Yvonne Brathwaite Burke to become the first Black woman elected to the California Assembly in 1966 and another 60 years until Diane E. Watson became the first Black woman elected to the state Senate in 1978,” Lee said. “The truth is that, 100 years after the 19th Amendment, the fight for universal suffrage is far from over.”

In the long view of time, progress has accelerated, and female political leaders have made great advances since the 1918 election and since women nationwide won the right to vote a century ago.

Assemblywoman Monique Limón (D-Santa Barbara), a Berkeley graduate and vice chair of the bipartisan California Legislative Women’s Caucus, sees her work as a continuation of the mission undertaken by Broughton, Dorris, Hughes and Saylor.

“Like the first four women to serve in the Assembly, many of the 167 women who served in the Legislature ran to increase representation and awareness of a variety of issues not often addressed, and most importantly, to serve and improve their communities,” Limón said. “I ran so that the decisions made in a state with over 50% of women have the input of women and so that issues which are a priority to women are not forgotten by the Legislature.”