Advertisement

The administration is pressing ahead with the first federal execution in 17 years as demonstrators seek changes to the criminal justice system and lawyers have trouble visiting death-row clients.

By Hailey Fuchs

WASHINGTON — Daniel Lewis Lee is scheduled to be executed in less than two weeks, but he has been unable to see his lawyers for three months because of the coronavirus pandemic.

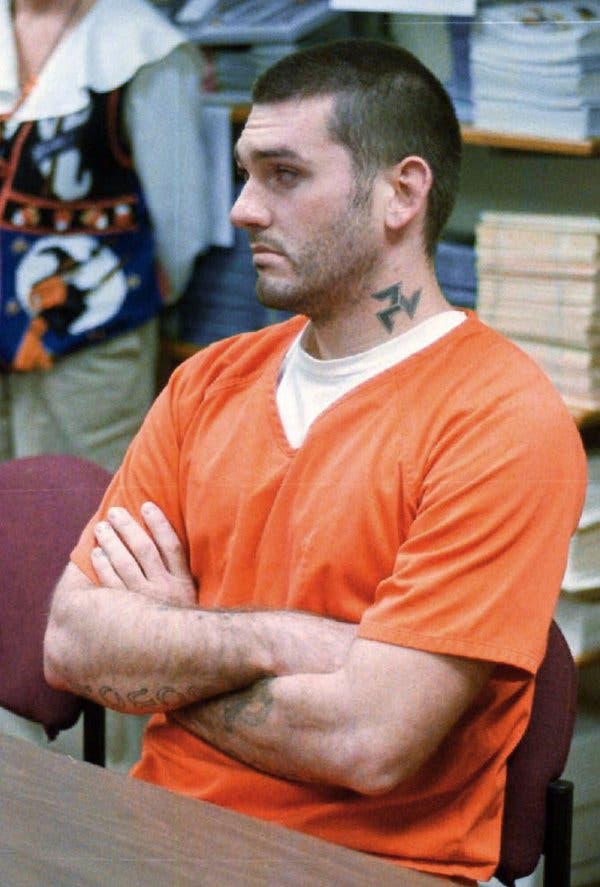

Mr. Lee, sentenced to death for his involvement in the 1996 murder of a married couple and their 8-year-old daughter, has been limited to phone calls, which one of his lawyers, Ruth Friedman, said she feared would jeopardize her client’s confidentiality. And amid a global pandemic that has put travel on hold, her team has been unable to discuss pressing issues with Mr. Lee, conduct investigations, or interview witnesses in person.

“I can’t do my job right. Nobody can,” Ms. Friedman said from her apartment 600 miles away, in Washington, D.C., where she is working to commute Mr. Lee’s sentence to life in prison.

If she is unsuccessful, Mr. Lee, 47, will be the first federal death row inmate to be executed in 17 years. Last year, Attorney General William P. Barr announced that the Justice Department would resume executions of federal inmates sentenced to death. Two weeks ago, Mr. Barr scheduled the first four executions for this summer, all of men convicted of murdering children, and to be carried out at the federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Ind.

On Monday, the Supreme Court cleared the way for the federal executions to proceed, rejecting arguments against the use of a single drug to carry out the sentence by lethal injection.

As the pandemic worsened, many states, including Texas and Tennessee, postponed scheduled executions of prisoners sentenced under state law. Since the pandemic began, there has been only one execution at a state prison, in Bonne Terre, Mo. The state capital trial in Florida for Nikolas Cruz, the gunman who killed 17 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, was delayed indefinitely. Courthouses closed or moved to remote operations to accommodate social distancing.

With a justice system barely cranking back to life, lawyers for the federal inmates on death row are struggling to work from home while their clients’ days are numbered.

The Terre Haute prison, like many across the country, has struggled to hold off the virus, registering eight cases and one death since the pandemic began. The penitentiary closed to all visitors on March 13; it reopened for the lawyers of the four men just last week.

But Ms. Friedman and the other lawyers are at an impasse: travel to the Terre Haute prison and risk their own health or stay home and risk doing less than they might be able to do otherwise — like conducting investigations or in-person interviews — to spare their client’s life.

“Whatever they do is going to be wrong,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. He questioned why the Justice Department would prioritize federal executions over the lives of those who might be exposed to the virus in the process.

“Nobody has to be executed now,” he said.

The Supreme Court struck down the death penalty in 1972, arguing that the laws violated the Constitution’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual” punishment. But amid rising rates of violent crime, the court reinstated the policy just four years later. Since then, a number of states have regularly carried out executions but the federal government has executed only three men as public support for it has fallen. The most recent execution, of Louis Jones Jr. for the rape and murder of a female soldier, was in 2003.

In announcing the schedule for this summer’s federal executions, Mr. Barr said the death penalty was the will of the American people as expressed through Congress and presidents of both parties, and that the four men scheduled to die “have received full and fair proceedings under our Constitution and laws.”

The summer’s scheduled executions mesh with President Trump’s increasing election year efforts to cast himself as a “law and order” leader even as his administration faces mounting criticism for its response to protests over systemic racism in the policing system and a deadly pandemic.

Mr. Lee, who is scheduled to be put to death on July 13, was a white supremacist who has since disavowed his ties to that movement. The Trump campaign has seized on the political ramifications of Mr. Lee’s planned execution, criticizing the president’s presumptive Democratic opponent, former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., for reversing his earlier support for the death penalty “even for white supremacist murderers!”

Though Mr. Biden now opposes capital punishment, he played a central role as a senator in the passage of the 1994 crime bill that expanded the use of the federal death penalty. Mr. Trump has repeatedly attacked Mr. Biden for his record on criminal justice issues.

Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump are far from the first presidential candidates to spar over the death penalty as a political tactic. In 1992, then-Gov. Bill Clinton denounced President George Bush for his inaction on crime. To affirm his support for the death penalty, he flew home to Arkansas in the midst of campaigning to personally see to the execution of a man who had been convicted of murdering a police officer.

But today’s candidates are vying for the White House amid nationwide protests over racism in the criminal justice system. Black people make up 42 percent of those on death row, both among federal inmates and over all, compared to 13 percent of the general population.

Though the four inmates scheduled to be executed this summer are white, critics of the death penalty warned that resumption of federal executions would only exacerbate the policy’s discrimination against people of color.

“It would be nice if they used those resources to address the widespread problem of police violence against Black people,” said Samuel Spital, director of litigation at the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense & Educational Fund.

Mr. Spital also questioned why the Justice Department did not use those resources allocated to resume federal executions to protect prisons from the coronavirus.

Imposing the death penalty amid the pandemic holds risks for those carrying out the execution: Doing so may require dozens of individuals, including corrections officers, victims and journalists, to come in close contact.

The Bureau of Prisons directed that face masks would be required for all individuals throughout the entire procedure, with violators asked to leave the premises. Social distancing will be practiced “to the extent practical,” but the bureau conceded that limited capacity of the media witness room might preclude their ability to maintain a six-foot distance between observers.

“The safety of our staff and the members of the community are of the utmost importance,” the bureau said in a statement.

Ms. Friedman is not sure if she will visit her client or attend Mr. Lee’s execution next month. After a 30-year career representing inmates facing their deaths, Ms. Friedman must decide for the first time whether or not to risk her own health or ask her colleagues, some of whom care for older family members, to risk theirs.

Several family members of Mr. Lee’s victims, his trial’s lead prosecutor, and the trial judge have all publicly opposed Mr. Lee’s execution. His co-defendant, described as “the ringleader” by the judge, was given a life sentence without parole.

In a statement, Mr. Barr maintained that the decision to reinstate federal capital punishment was owed “to the victims of these horrific crimes, and to the families left behind.”

But Monica Veillette, who lost her aunt and cousin to Mr. Lee’s crimes, does not believe that this execution is for her family. She has asthma, and both her grandmother and parents are older. If they travel to Indiana for the execution from Washington State and Arkansas, each of them could be put at risk of contracting the virus.

“If they owe us anything, it’s to keep us safe now by not pushing this execution through while people are still scrambling to access disinfectant spray and proper masks,” she said. “Haven’t enough people died?”

-

-

-

- Here are 13 women who have been under consideration to be Joe Biden’s running mate, and why each might be chosen — and might not be.

-