Advertisement

Politically endangered Republicans are scrambling to make their contests referendums on China rather than the coronavirus pandemic.

WASHINGTON — When Senator Martha McSally, one of the most politically endangered Republicans, was asked last month about reports that President Trump had brushed away warnings from his own aides about the looming threat of the coronavirus, she promptly pivoted.

“I learned the day I entered the military, never trust a communist,” Ms. McSally answered. “China is to blame for this pandemic and the death of thousands of Americans.”

Her campaign went further, turning the sound bite into a television advertisement that has blanketed airwaves across Arizona, where polls show her badly trailing her Democratic challenger, Mark Kelly. And the Senate Republican campaign arm has sought to portray Mr. Kelly as beholden to Beijing, broadcasting a commercial that features an announcer saying the Mandarin transliteration of his name as Chinese characters flash across the screen.

Fighting for their political lives amid twin domestic crises — a pandemic that has battered the economy — vulnerable Republican senators running for re-election are working to divert voters’ gazes half a world away and make their races a referendum on China. The tactic, party strategists say, is a way for Republicans to avoid defending the president’s handling of the virus, which has been met with widespread public disapproval, and instead offer up an alternative issue that already inspires fear and skepticism among voters.

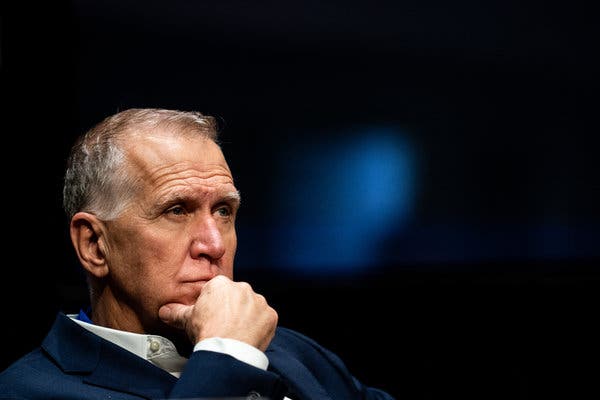

Facing plummeting standing in the polls and few upbeat messaging options, Ms. McSally and several other Republicans have leaned heavily into the message. Senator Thom Tillis of North Carolina released a five-point strategy last month meant to hold the Chinese government accountable for its “lies, deception and cover-ups.” A video of him standing in front of a poster, labeled “the Tillis Plan” in all capital letters, breaks down each point. In Montana, Senator Steve Daines, who is facing a challenge from the state’s popular Democratic governor, Steve Bullock, unveiled a digital and television ad campaign centered on casting China as responsible for the virus. Senator Joni Ernst in Iowa posted on Twitter and Facebook condemning “so many bad actions out of China.”

“If only they had stood up and alerted the world much sooner, the pandemic could have been lessened,” she said.

The strategy comes as hawks, especially Republicans, are ascendant in Congress and jockeying for the role of lead China thought leader, and as national security experts in both parties warn a new era of great power competition between the two nations has begun. And while it is unclear whether an anti-China message will appeal to voters at a time of mounting domestic turmoil, some Republicans believe it may be the most effective message they have.

Neil Newhouse, a leading Republican pollster, said that both private and public polling indicated that Americans, regardless of political affiliation, had markedly negative feelings toward China over issues including trade and technology theft.

“It becomes an easy punching bag for politicians, both Republicans and Democrats,” he said in an interview.

For Republicans in particular, Mr. Newhouse said, the strategy “allows them to go on offense, to be aggressive, to take a strong position.”

The hope, according to strategists advising Senate campaigns, is that China will become a wedge issue, forcing candidates to take a position viewed through the lens of either strength or weakness, and putting America first — as Mr. Trump often frames it — or letting the nation lag as a global leader.

The strategy was devised, at least in part, by Brett O’Donnell, a veteran Republican strategist with ties to two of the party’s fiercest China hawks, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas. In a 57-page memo circulated to candidates in April by the National Republican Senatorial Committee, Mr. O’Donnell outlined a coronavirus messaging strategy that focused on attacking China and largely avoided mention of Mr. Trump.

Predicting that candidates are likely to field questions about whether Mr. Trump was at fault for the nation’s response to the virus, Mr. O’Donnell advised: “Don’t defend Trump, other than the China travel ban — attack China.” The memo was first reported by Politico.

China hawks like Senator Josh Hawley, Republican of Missouri, argue that the message has long resonated with voters at home.

“The typical, ordinary, normal everyday voter in my state at least, in Missouri — if you ask them what they think about China, they’d say they think they’re a threat, they’re a competitor, they’re an opponent,” Mr. Hawley, who is among the lawmakers with rumored presidential ambitions jockeying to lead an aggressive China policy, said in an interview. “Working voters have been concerned for years about China cheating on trade, taking their jobs, and the military threat.”

Republican strategists carefully watched reaction to the House campaign of Kathaleen Wall, who ran in a Republican primary race in Texas to succeed Representative Pete Olson, who is retiring. Ms. Wall released a provocative advertisement that began “China poisoned our people” and called the country “a criminal enterprise masquerading as a sovereign nation” as a picture of President Xi Jinping of China flashed in the background. Strategists believe the breakout ad, which Democrats condemned as racist, played well among voters.

But that was a primary contest in a conservative part of Texas. Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado, who is also in a difficult re-election race in a state that has steadily trended more liberal, has largely stayed away from the strategy.

As the chairman of the Foreign Relations subcommittee on East Asia, Mr. Gardner has a clear record to praise of his efforts to press the Chinese government on human rights abuses, including legislation he championed urging Beijing to end the continued persecution of its own citizens through the use of intrusive mass surveillance.

No one has emphasized the anti-China message more than Ms. McSally, whose race has particularly troubled Mr. Trump’s advisers and the president himself, to the point where he repeatedly asked if her candidacy was hurting his own prospects in a state that has become more competitive.

“This election is going to be about who can stand up to China, the world’s communist bully,” Ms. McSally wrote on Twitter. “I will stand up for freedom and against the oppressive Chinese regime, which has wrought so much death in our world.”

Some members of the Trump administration have sought to give Ms. McSally a political lift by supporting the decision of a semiconductor manufacturing company in Taiwan, T.S.M.C., to locate a new factory in Arizona, according to a person familiar with the plans. The company announced May 14 that it would invest $12 billion over the next decade to build a chip making plant — a move that represented a serious challenge to China’s technology ambitions.

Ms. McSally lauded the announcement, which will create 1,600 jobs in her state, as “fantastic news for Arizona and America, and bad news for China.”

Party officials believe the message is especially potent for Ms. McSally because her opponent Mr. Kelly, a former astronaut, has business ties to China. A space exploration company that Mr. Kelly helped found, World View Enterprises, has received investment from the Chinese internet giant Tencent Holdings, among others. World View has said that Tencent does not play an active role in the company, and Mr. Kelly’s campaign has said that he views China as an adversary.

But Republican strategists still see an opening to negatively define Mr. Kelly, who has positioned himself as a bipartisan figure, hoping that playing the China card can pull in a portion of voters who support Mr. Trump but not Ms. McSally.

This month, the campaign arm of Senate Republicans released the advertisement accusing Mr. Kelly of “covering for China” on the coronavirus, featuring clips of him giving speeches there, complete with the audio overlay of his name in Mandarin.

Mr. Kelly’s campaign said that Ms. McSally was willfully misrepresenting his views on China, and noted that he had military experience in the region.

“Mark has long said that the Chinese government is an adversary, not because of how the political wind is blowing, but because he was stationed in the western Pacific and saw for himself how growing Chinese influence is a threat to American interests and our democratic partners,” a spokesman said.

But Ms. McSally’s advisers indicated that she would continue the China-related attacks, which they said had broad resonance in the race.

“Voters want China to be held accountable,” said Terry Nelson, a strategist advising Ms. McSally’s campaign. “You can pretty much go anywhere and there’s a concern.”

Ana Swanson contributed reporting.