Morgan Kollin is exhausted. During a video interview from his home near Detroit, Michigan, he nods and blinks repeatedly against fatigue.

The 40-year-old is the founder and chairman of Youmacon, Michigan’s largest anime convention, with a 15-year history and an annual draw of 23,000. Youmacon is scheduled to take place as an in-person gathering on Halloween weekend, Oct. 29 to Nov. 1 — though many think it shouldn’t.

For the past few months, Kollin has been struggling to keep things together for the sake of his staff and his well-being. When asked if he sleeps much, he shakes his head. “Not remotely,” he says.

The reason for Kollin’s restlessness may seem counterintuitive. After spending a year preparing for his convention, he is now seeking permission to cancel it.

The technicalities of U.S. law have him hoping that local politicians will soon officially prohibit all large public events in his region, granting him the legal right and, critically, the financial support to shut Youmacon down.

“At this point, we’re the last man standing,” he says.

The term for such permission is force majeure, a contract clause enabling all parties to walk away from their obligations in the face of a massive and unforeseeable event, such as a pandemic.

It’s a phrase that’s suddenly on the lips of event organizers across the United States.

While the calendar says it’s only September, the year is already over for the majority of anime conventions. Of the estimated 62 anime-dedicated events planned across the country in 2020, nearly all had to cancel or postpone, leaving tens of thousands of fans, dealers, distributors, volunteers and guests, not to mention hundreds of hospitality venues and transportation services, in the proverbial lurch.

Like the virus itself, the contagion of cancellations spread from Asia to the West. For anime conventions it started in Tokyo at the end of February, with the nixing of AnimeJapan 2020, the industry’s annual domestic trade fair.

Announcements multiplied in the spring. In late March, even legacy events scheduled for May, such as Chicago’s Anime Central and A-Kon in Dallas, folded their tents one after another. By the close of April, an entire slate of big name summer conventions, including Japan Expo in Paris and the San Diego Comic-Con, was wiped clean.

In some ways, the summer conventions had it lucky. By the time the virus’s continued spread became self-evident, two of the largest, Anime Expo (AX) in Los Angeles and Otakon in Washington still had over two months of lead-time to announce their decisions and make plans to host virtual events.

But last-minute cancellations saw many spring conventions scrambling to cut losses, and, in some cases, pay for them.

Kansas’ Naka-Kon was forced to pull the plug by local officials in mid-March, one day before opening its doors, with customers, performers and exhibitors from around the world already on site, pre-registering and checking in to hotel rooms.

According to Treasurer Takuya Jay Inoue, Naka-Kon could not recoup its pre-convention costs and may not survive another year.

“The situation and the timing was the worst it could be,” he says. “Not only the loss of income hurt, but we had everything set up and ready to go. For us, termination is definitely a possible outcome.”

A. Jinnie McManus, founder of the private Facebook group, We Run Anime Cons, has been tracking the experiences of convention runners nationwide. Some states, municipalities and local businesses have been sympathetic, waiving fees and sharing the burden with organizers in the spirit of community.

Her own event, Colorado Anime Fest in Denver, for which she is communications director, was fortunate to be in a state that had warned against large gatherings and eventually banned them — enough to trigger the force majeure clause.

Even before the state’s official declarations, however, local venues in Denver, including the Denver Marriott Tech Center Hotel, the main site of the convention, supported cancellation.

“But not all cons have contracts that even allow for government intervention,” McManus says. “In some places, that’s seen as ‘big government,’ so it isn’t acceptable. There are cons in the U.S. that have spent thousands of dollars to cancel their own event.”

Even insurance isn’t a sure thing. Many U.S. providers dropped pandemic coverage as early as January, according to McManus, a maneuver that stranded service industry businesses, and left some conventions with no recourse but to hold a limited version of their show, or fight even harder to shut it down.

“When you work year round for these things, to then have to turn around and work hard again to cancel your event because you know it’s the right thing to do, it’s one of the most heartbreaking decisions you can make,” she says.

Anime conventions are finding — or at least looking for — a new normalcy online. On the first weekend in May, just after the avalanche of aborted event notifications, many fans were surprised by news of a virtual convention that emerged seemingly out of nowhere called Anime Lockdown.

Streamed on Discord, Twitch and YouTube from May 1 to 3, Anime Lockdown was the brainchild of two 34-year-old veteran convention-goers: John-Paul Natysin, a sound engineer in New York, and his Minneapolis-based programmer friend, Tony Bowe. The two ran the entire show out of their own homes.

The idea came to Natysin after the cancellation of Minnesota’s Anime Detour, which both men had planned to attend. He posted an announcement from an account he opened on Twitter in April. In the void created by convention closures, that’s all it took.

“We picked the right time,” he says. “There was nothing going on back then, and that played a really big role in us getting word of mouth.”

The three-day event presented 25 panels hosted by 28 guests and drew an average of 100 to 300 viewers, with one Sunday panel exceeding 800.

Despite its brief gestation period, Anime Lockdown featured lead U.S. voice actors Veronica Taylor from “Pokemon” and Kyle Herbert from “Dragonball Z,” “Naruto” and “Bleach,” and major anime publisher-distributors Discotek Media and Right Stuf Anime.

It was also amusing. Announcements of fictional on-site incidents (a wedding reception in the hotel ballroom, a faulty elevator delaying festivities) that regularly beset many conventions in physical spaces made the virtual gathering feel more like real life offline.

According to Natysin, the guests were the biggest surprise. They mostly came unsolicited, reaching out to him on Twitter.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “I think some of them just felt bad for me, but also, at the time, they probably had nothing better to do.”

News of Anime Lockdown’s relative success spread fast on social media, raising expectations for the potential of virtual programming, and putting pressure on official organizations to provide some kind of online substitute.

In Japan, Comic Market (Comiket) 98, the largest fan-artist convention in the world, with roughly half a million participants at each of its biannual summer and winter events, ran its first virtual convention, Air Comiket, from May 2 to 5.

Comiket emphasizes the print sales of artwork created by fans. For its internet replacement, Air Comiket sold physical books through ecommerce sites featured on its livestream feed, recording 443,357 views over four days and brisk online transactions.

Over the summer, Comiket announced that its winter edition in December would also take place entirely online, together with a commemoration of the event’s 45th anniversary.

In a matter of months, virtual events have become practically de rigueur in the anime industry, partly to engage with its community of supportive fans, but also, to a lesser extent, sustain the commercial branding and sales of its companies. Veteran producers and distributors, Sony’s Funimation and Warnermedia’s Crunchyroll, also held conventions online in July and early September, respectively.

Nevertheless, coordinating a virtual convention is uncharted territory for most event runners, and presenting one effectively often involves having technical skills and hiring third-party operatives to augment a convention’s in-house staff.

Otakon Online hosted 45 hours of programming on six streaming channels over the course of a single day in August, including live streams from Japan. They used Twitch to deliver video, and a cloud-based production site called Stage Ten, reaching more than 61,000 live views.

It was a lot to juggle, admits Edwin Peregrina, Otakon’s engineer-in-charge. While a few balls got dropped, others stayed airborne, magically.

“We know we were punching above our weight,” Peregrina says. “At times we were pushing too hard and that may have led to some hiccups in our stream.”

The success of a panel streamed live from Japan on “Carole & Tuesday,” Shinichiro Watanabe’s (“Cowboy Bebop”) latest series, thrilled Peregrina. The stream featured a real-time musical performance by Tokyo-based singer-songwriter, Celeina Ann.

“When she started singing with a pristine picture and sound, it wasn’t lost on me what we were accomplishing,” Peregrina says. “Bringing in a broadcast quality feed to my home basement and then streaming it out to the world was a very proud moment. I would be lying if I said I didn’t shed a tear or two.”

AX’s virtual replacement, AX Lite, came together in a single month in July. Ray Chiang, CEO of the Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation (SPJA), the nonprofit company behind AX, started thinking about canceling the physical event in February, when AX’s biannual industry gathering, Project Anime Tokyo, was shuttered.

“Profit and income were already out of the equation,” he says. “What we cared about was relevancy, engaging with our fans and educating the public about the industry. A virtual digital platform was our only option.”

AX Lite recorded more than 500,000 views from 70 countries and territories. Roughly half of their ticketed fans rolled their purchases over to the 2021 event, and, more significantly, 80 percent of exhibitors have committed to returning next year.

Anime NYC is exploring a similar option for its November dates, but there are hitches.

Fans are showing signs of “Zoom fatigue,” a growing weariness with anything online that resembles yet another conference call.

Also, one of the biggest challenges has been converting high viewership numbers into online purchases. Convention exhibitors and dealers are seeing a fraction of their usual sales from this year’s virtual events.

Anime NYC founder and Show Director Peter Tatara of LeftField Media says that after a summer of virtual events, it’s time to have conversations across the industry about what works and what doesn’t. He sees the need to capture the spirit of conventions by altering the medium to better suit online behavior.

“The initial approach was to just take what’s on the floor and put it on the internet,” he says. “But the reality is that people don’t experience both the same way. Revenue for artists and distributors has been pennies compared to what they’d get at a physical show.

“We need to present content in a way that’s more native to the online world. I don’t think we’ve seen success in hour-long panel presentations that are simply Zoom meetings with personalities or celebrities.”

In the events business, anime conventions face an additional hurdle: Many have become so reliant upon guests from Japan that even if COVID-19 is managed domestically in the United States, international travel restrictions and reluctance may hamper future live shows.

In both countries, the pandemic is most damaging to mid-sized players that have overhead costs but fewer assets and resources to help them survive a year without income.

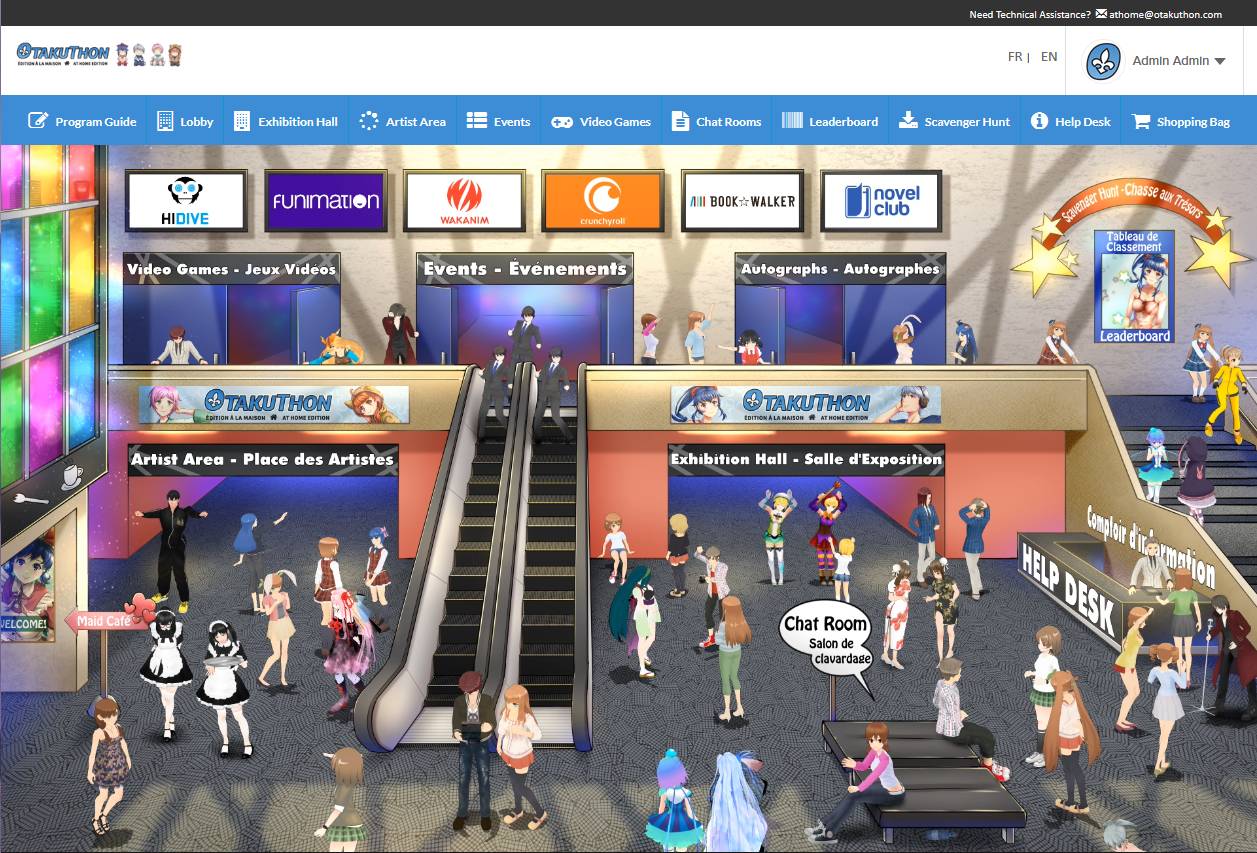

Some have kept busy and visible by donating personal protective equipment to local hospitals. Otakuthon, a mid-sized event in Montreal, Canada, charged a modest fee for its online offerings, posting virtual graphics that simulate its specific physical environments (right down to fan avatars in the lobby) and stressing constant interactivity.

And a few smaller conventions, notably in the U.S. state of Florida, a COVID-19 hot spot, have gone ahead with in-person gatherings anyway, potentially putting lives at risk.

Benjamin Torres, a Florida teacher who attended one such convention wearing full personal protective equipment in August, found health precautions insufficient.

“It was an instance of purely random and irresponsible celebratory chaos,” he says. “Conventions once served as places of escape. How long till our escapes are politicized?”

Back in Michigan, Youmacon’s 16th event is still on for Halloween weekend. In desperation, Kollin posted a blunt and candid statement on the convention’s website titled “Transparency” to reveal his legal dilemma — information that is rarely disclosed to the public by event organizers.

“This is not a simple matter of being out of a bit of money this year,” he wrote.

The Michigan Renaissance Festival, the state’s largest event with more than 200,000 attendees annually, was called off last month for the first time in its 41-year history over COVID-19 concerns. What would be bad news in an ordinary season has given Kollin hope that the same will happen to Youmacon. For him and his staff, however, the decision is not just theirs to make.

Roland Kelts is author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” and a visiting lecturer at Waseda University.

Your news needs your support

Since the early stages of the COVID-19 crisis, The Japan Times has been providing free access to crucial news on the impact of the novel coronavirus as well as practical information about how to cope with the pandemic. Please consider subscribing today so we can continue offering you up-to-date, in-depth news about Japan.