There he is, tucked behind the red-vinyl booths of a tiny luncheonette, beaming from a campaign poster. And there he is again, his name emblazoned on the downtown station of his beloved Amtrak. All throughout his hometown, there are signs of Joe Biden, like a Wilmington version of “Where’s Waldo,” the red-striped T-shirt swapped out for that trademark toothy grin.

At Claymont Steak Shop, multiple Bidens beam from a framed photo collage with line cooks and cashiers of this famed cheesesteak joint in the suburb where he spent his formative years.

Everybody in town has a Biden story, and Larry Lambert, sitting at a table not far from the display, is sharing his.

After his father’s death, Lambert found himself unable to afford his final years at Temple University. His last-ditch effort was to appeal to then-Sen. Biden, who had honored Lambert’s achievements with the Boys & Girls Club a few years before. Biden wrote a letter to the office of financial aid.

“The next thing I know, they said that they would pay for everything, room and board, just immediately on the spot,” said Lambert, now a candidate for state representative. His campaign fliers prominently feature a photo of him with Biden.

Biden’s intervention nearly 20 years ago earned him Lambert’s continuing affection and loyalty, but not Lambert’s vote in this presidential election.

“I’ll just say that as much as I love Joe Biden, I just want to ensure that the person that we choose to be our next president is really on the right side of the people,” he said.

This could be seen as an allegory for Biden’s uneven presidential bid. The former vice president has a deep reserve of goodwill from Democratic primary voters, but as the returns from early contests show, that admiration has not translated into victories.

Brandywine Creek runs through Wilmington, Del., longtime home of Joe Biden.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Lambert’s tale also has implications closer to home, signaling limitations to the clubby, collegial way of doing politics that Delaware — and especially Wilmington, its most populous city — long embraced.

The local political culture even has its own name, the “Delaware Way.” Biden, with his unshakable faith that personal relationships prevail over partisanship, is the Delaware Way on steroids. But just as Biden comes under fire from progressives in the presidential race, back home, the Delaware Way is fraying, as residents take stock of the loss of major employers, high crime and persistent inequality, and wonder whether the status quo is no longer good enough.

Lambert, 39, laughed broadly at first when confronted with the incongruity of it all — the man enabled his college education, for Pete’s sake; what more does it take to win his vote? But asked whether he felt conflicted, he grew serious.

“Very.”

Joe Biden visits Gianni’s Pizza in Wilmington last spring.

(Jessica Griffin / Philadelphia Inquirer)

::

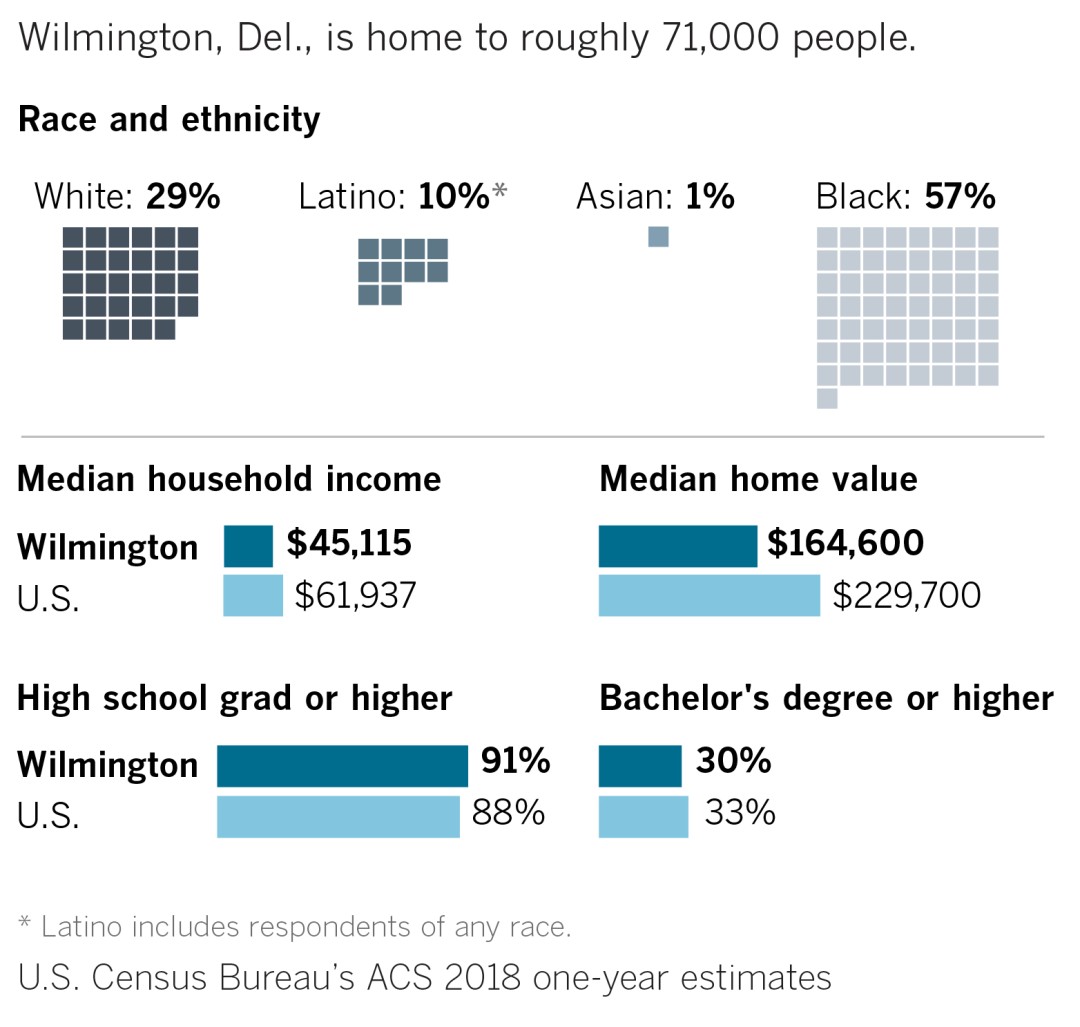

Wilmington is home to roughly 71,000 people, a city wedged between the confluence of the Delaware and Christina rivers. It is the biggest city in the state, but residents describe it more as a small town where relationships and reputation are the local currency.

“Nobody cares what college you went to,” said Coby Owens, a Democratic activist now running for Wilmington City Council. “They care about what high school you went to.”

Biden went to high school in nearby Claymont, where Lambert is also from, but for decades he has lived in Greenville, a community just outside Wilmington where residents are wealthier, whiter and more conservative than those of the city.

On the tree-lined lane where Biden lives, the house styles include French chateaus and multi-story Tudors, all uniformly grand. The former vice president’s house is tucked away, largely shielded from view by the guardhouse at the entrance.

It’s a short drive into the heart of Wilmington — past neighborhoods of red-brick row houses, a commercial strip of car dealers and then into downtown, where skyscrapers bear corporate logos, where the rustic woods of Greenville can seem like worlds away.

Row houses along 2nd Street in West Wilmington, Del.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Biden is a common thread, running through the area’s most prosperous enclaves and its most disadvantaged. (His campaign declined to make him available for this story.)

There’s the Joseph R. Biden Aquatic Center, where Biden worked in the early 1960s as the sole white lifeguard in a largely black community. He met Dennis Williams, who grew up to be a policeman, a state legislator and the city’s mayor, but at the time was a mischievous kid who would run and do flips around the pool in defiance of the rules.

“He used to throw me out of the swimming pool because I used to curse and do bad things,” Williams said.

Williams can still picture Biden driving around in his Volkswagen with a burnt-out clutch, a clunker that required a push to get started, as he attended pizza parties and soul food dinners and baseball games.

“I was puzzled why he was always around,” Williams said. “But as I got older and he was still hanging around, I was impressed. This guy was genuine.”

There’s the Joseph R. Biden Jr. Railroad Station, where Biden would give Lee Murphy, a longtime Amtrak conductor, a ride home after their train pulled into town.

“I’ve never voted for Joe Biden and I told him that,” said Murphy, a Republican who is running for Congress. “But personally I like him. He’s a likable guy.”

Angelo’s Luncheonette on North Scott Street in Wilmington, where Biden and his family were once frequent diners.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

John Powell, a retiree living in the suburb of Hockessin, carries Biden in his pocket; he’s quickly able to summon a video on his phone of the septuagenarian swapping train trivia with Powell’s 11-year-old grandson and instructing the youngster to tell his “grandpop” hello.

“Well, that’s Joe,” said his wife, Anne, matter-of-factly.

“That’s Joe,” Powell agreed. “That’s just how he is.”

The Biden sightings are less frequent in the thick of the presidential campaign, but in December there he was at the riverfront convention center, raising money from just shy of 400 guests including the governor, both U.S. senators and the state’s sole congressional representative.

Within a minute of grabbing the microphone, his voice broke as he started to cry.

“There is a Delaware Way,” Biden said. “It fades every once in a while, but it’s still here in Delaware.”

It’s a practice borne out of Delaware’s diminutive size, a sense that the state is small enough to get all the decision-makers together in a room to hash out agreements in a spirit of neighborly cooperation. In the state’s southernmost county, there’s a tradition of political opponents actually burying a hatchet after election day to signal an end to the hostilities of campaigning.

A high school marching band participates in a parade in the Wilmington suburb of Claymont.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

The premium on civility is so deeply ingrained that Jesse Chadderdon, the executive director of the state Democratic Party, has childhood memories of watching coverage of the bitingly negative 1988 presidential campaign between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis and feeling something was amiss.

“I do remember having this vibe very early on that things in Delaware both were and were supposed to be more congenial than that,” he said.

Biden’s political life began when Delaware was a solidly Republican state. Even as it became more liberal, there was still a sense of cross-party affability: most notoriously in 1992 when GOP Gov. Michael Castle and Democratic Rep. Tom Carper ran for each other’s posts with little opposition, a move now known as “the swap.”

Ted Kaufman, a former Biden aide, credits Biden not just with ascribing to that amicable brand of politics, but with molding it.

“He was kind of the person who helped create the Delaware Way,” said Kaufman, who was appointed to fill Biden’s Senate seat after the 2008 election. “One of the things I think he’s famous for is constantly saying to his colleagues, you can question people’s positions and judgment but never question their motive.”

Buildings rise beyond Brandywine Creek in Wilmington, Del.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

For Biden’s allies, his bent toward aisle-crossing is not just a sign of his friendly disposition, but political pragmatism.

“He’s telling the truth. It does work,” said Williams, a Democrat who recalled serving in the state Legislature when the GOP held control. He would take Republicans to dinner in a bid to finagle resources for his district, until the time came when the Democrats took control and he chaired the powerful finance committee.

“When they came to me and needed things for their districts like pools and parks and tennis courts and things of that nature, I didn’t forget them because they helped me,” Williams said. “You can’t do people wrong when they’ve done you right, because when the house falls on you, it’ll fall hard.”

::

Edward Harrison knows there’s this concept of the “Delaware Way.” But he doesn’t find it particularly relevant in his neighborhood, 10 minutes south of Wilmington, where he owns a barber shop and cafe. And certainly not in the poorest neighborhoods of the city itself, where Harrison used to live.

“For me, it’s not very connected to the people,” he said.

Edward Harrison, who owns a barbershop and cafe outside Wilmington, see problems with the so-called Delaware Way.

(Melanie Mason / Los Angeles Times)

Harrison, 56, sees politics not as a series of agreements among neighbors, but as a necessary evil that has failed to fix the persistent problems of education and economic opportunity. Tony suburbs like Greenville may enjoy stability and civic engagement, but Harrison’s Wilmington is “disenfranchised, disinterested.”

“This is an environment that’s always been teetering,” he said, before correcting himself. “Well, it is now. I don’t want to say always, because it was better.”

When Harrison first moved here from Philadelphia as a child, there was ample opportunity for blue-collar workers. General Motors had an assembly plant in town and Chrysler was nearby. Claymont, up the river, had a steel mill.

But the Chrysler plant shut down in 2008, quickly followed by GM closing. The steel mill shuttered seven years ago. As those jobs disappeared, Harrison said, the city “nosedived.” Gun crimes spiked in that time; Wilmington ranked third in violence among 450 comparably-sized cities in 2013, according to the Delaware News Journal.

For white-collar workers, there’s also been upheaval. For nearly 200 years, Wilmington had been shaped by its signature employer, DuPont Co. The company evolved from making gunpowder into a chemical manufacturing powerhouse, famous for inventing neoprene, Lucite and Teflon.

At one point, according to the News Journal, 1 in 10 Delaware workers were on the payroll of “Uncle Dupie,” which was headquartered downtown. A series of mergers and spinoffs have jolted the company, which has dramatically shrunk its presence in town.

A pair of vacant buildings frame the Chase Bank building in the distance in big-business-friendly Wilmington, Del.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Delaware’s other signature industry, banking, remains a strong presence, but has gone through a roller-coaster of expansions and contractions.

The loss of these major employers has left residents feeling unsettled, even though the unemployment rate in Wilmington is low — just under 4% — and employers in the service industry are hungry for more hires in this tight labor market.

“There are jobs. But they don’t pay nearly what they used to pay,” said Bill Dunn, a 60-year-old former engineer for DuPont who retired in 2016, earlier than planned.

Gun violence remains at the top of residents’ minds. Last year, overall crime dipped by 3%, the second year of decline. But there were still 112 shooting victims, a 42% increase from the year before, and 21 of those victims were juveniles.

Pockets of the city show signs of new energy. On the banks of the Christina River, a new seasonal beer garden has become a popular draw where patrons can sip craft brews and practice chucking axes at wooden targets. A row of new restaurants and bars on Market Street in downtown has made a once-desolate strip into a dining destination.

But some in the city’s black community, which comprises close to 60% of the population, chafe at the changes, seeing displacement instead of opportunity.

Youths play basketball on a court beneath Interstate 95 in West Wilmington.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

“Take a picture of that Rainbow shop,” said Jakim Muhammed, a community activist, pointing out a low-cost clothing store among the newer restaurants. “I guarantee you that two years from now, that Rainbow shop will not be here. It’s not part of [what] they’re trying to build over here.”

In many ways, Wilmington is not much different than other cities across the country and the world, seesawing between economic growth and persistent inequality.

To explain this duality, some in town blame the homegrown phenomenon, the Delaware Way.

“There’s a consistency in how things are handled. Government functionality,” said Dunn. But with decisions being made by a chummy group of insiders, he said, the Delaware Way also encompasses “the horse-trading going on, the games being played.”

Residents, he said, “started getting more and more vocal about their contempt for it.”

For many, the Delaware Way has begun to symbolize the punches being pulled, the turfs being guarded, even in the face of daunting challenges in the state’s struggling educational system or enduring poverty in some pockets of town.

After moving to Wilmington from Camden, N.J., Atnre Alleyne, an education policy specialist, was invigorated by how easy it was to get access to top officials.

“And then you get here and you see that even with all of that, the bolder, bigger things that need to happen aren’t always happening,” Alleyne said.

The Christina River in Wilmington, where new commercial and residential developments have taken over old industrial sites along the waterfront.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Alleyne, 35, was amused by local sensitivities after he published op-eds accusing politicians of “prioritizing compromise” or, after early childhood education funding was slashed, of “lying to babies.”

“The stuff I say here — in New York or Philly or L.A., it would be nothing,” he said. “But here it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh!’”

Lambert, whose connection to Biden enabled him to complete his degree, said the Delaware Way had harmed, not helped, this community, because it gives outsized power to business interests. He points to the state’s reliance on taxes on companies incorporating here — projected to be nearly 30% of next year’s revenue — that shapes business-friendly policies, such as Delaware’s minimum wage, which is lower than that of its neighbors.

“It’s almost like a symbiotic relationship between like corporations and politics,” Lambert said.

These days, Biden’s presidential run is in part a campaign to take the Delaware Way national — an insistence that America’s salvation lies in a return to the politics of relationships.

As he’ll often say on the trail, he tends to get hammered for this sentiment, mainly by progressive Democrats who find it outdated and naive in this era of polarized rancor.

Nancy Willing, a Democratic political blogger whose site is aptly named “The Delaware Way,” wondered if the state’s days of ticket-splitting are over.

“I used to vote for Mike Castle. I always voted for a moderate Republican when appropriate — I always felt comfortable with that,” she said. “But contemplating right now whether any of my Republican friends would ever vote Biden? I really don’t think so. I think that really has significantly shifted.”

The intersection of 4th and Market streets in downtown Wilmington, Del.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Progressive Democrats are increasingly eager to challenge incumbents. In 2018, a little-known activist named Kerri Evelyn Harris garnered an endorsement from fellow insurgent candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in her race against Sen. Tom Carper, who ultimately won handily. Sen. Chris Coons, up for reelection this year, is also facing a challenge from an opponent to his left.

Activists are blunt about the uphill battle of taking on some of the state’s best-known political figures. But they point to victories down-ballot, particularly in electing progressive candidates in the Statehouse, as a sign that the identity struggle in the Democratic Party that is playing out in the presidential campaign and all over the country is also taking root here.

The future of the Delaware Way may boil down to whether compromise, its central feature, is seen as a virtue or a vice.

“I never thought of myself as a conservative Democrat, but I really was until 2016, and now I am much more progressive,” said Anne Powell, 68, who has become more politically active since President Trump’s election. “So yeah, it can be a problem.”

Her husband, John, who volunteered for Biden’s campaign, sees more merits in the old ways of doing business.

“Maybe it’s my age,” said John, 68. “But I wish we could go back to [when] the politicians could go into a room, and say, ‘Here, I’ll give you this if you give me that,’ and actually get two things done.”