Advertisement

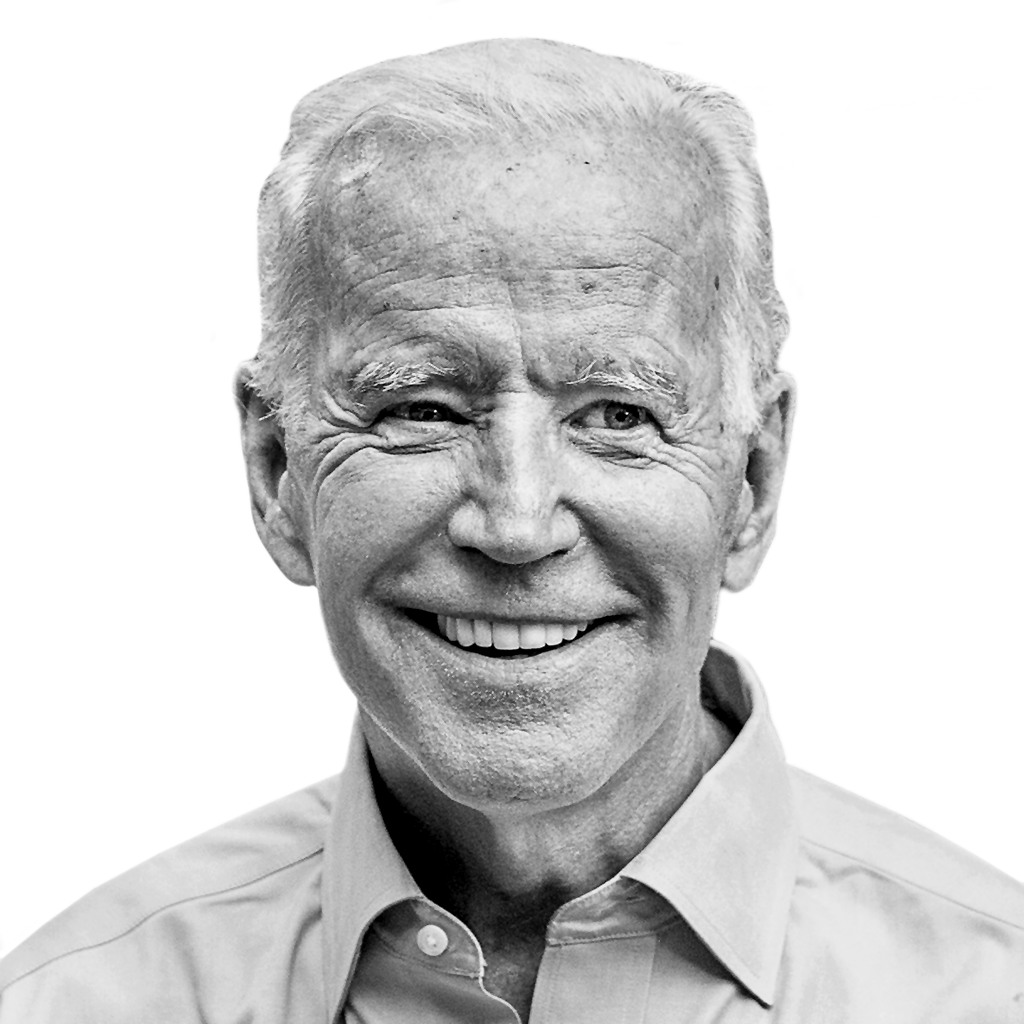

Joe Biden is looking ahead to South Carolina to resurrect his candidacy. There are signs that it may be a bigger challenge after defeats in Iowa and New Hampshire.

COLUMBIA, S.C. — Even before the final results from New Hampshire showed Joseph R. Biden Jr. finishing a distant fifth there, the former vice president had flown to South Carolina on Tuesday night for a gathering of enthusiastic supporters. A gospel choir sang about salvation, a fitting choice for a candidate who is counting on this state’s large black electorate to save his third try for the White House.

“Up to now, we haven’t heard from the most committed constituency of the Democratic Party, the African-American community,” Mr. Biden told about 200 attendees, many of them black. He added: “99.9 percent. That’s the percentage of African-American voters that have not yet had a chance to vote in America.”

The ability to mobilize black support in South Carolina, which holds its primary on Feb. 29, and across the South has long been the foundation of Mr. Biden’s candidacy — a presumed advantage that would highlight his capacity to forge a diverse coalition to take down President Trump.

Yet as Mr. Biden looks to black voters to resurrect his candidacy after defeats in both Iowa and New Hampshire, cracks have appeared in that support, in some polls and among influential local and national Democrats, who are saying out loud what many have privately believed all along: that he was a safe, familiar political harbor for them as much as an object of affection.

While Mr. Biden remains the favorite among many state party leaders, several South Carolina Democrats say that another candidate, Tom Steyer, has become a significant factor in the primary race here. Mr. Steyer, a billionaire from California, has been aggressively courting black voters, spending heavily on advertising and lavishing money on businesses across the state.

Political advantages that once seemed a formality for Mr. Biden’s campaign — like the endorsement of the state’s most powerful Democrat, Representative James E. Clyburn — are now uncertain; two people familiar with Mr. Clyburn’s thinking say he is increasingly worried about endorsing a candidate who is not guaranteed to win the state.

Two other black Democratic officials in the state on Wednesday endorsed one of Mr. Biden’s rivals, Pete Buttigieg, who had struggled for most of the campaign to attract any African-American support.

And a new poll this week showed Mr. Biden’s support among black voters nationally had fallen from 49 percent last month to 27 percent this month.

“The thing about it is, I don’t know how much real solid support he ever had,” said JA Moore, a state representative from Charleston, S.C., who had come to Mr. Biden’s party Tuesday to listen but was not convinced. Mr. Moore was one of the Democrats who endorsed Mr. Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., who finished well ahead of the former vice president in both Iowa and New Hampshire.

Black voters make up about 60 percent of the Democratic electorate here, and the Biden campaign expressed confidence they will buoy his candidacy in the primary in a little over two weeks.

“Relationships matter, relationships count, and your history counts,” said Kendall Corley, Mr. Biden’s state director, nodding at the former vice president’s deep connection to a state he has been visiting for decades.

State Senator Marlon Kimpson, a Democrat who has endorsed Mr. Biden, insisted that voters of color in his Charleston-area district would not take cues from the heavily white states of Iowa and New Hampshire.

“Many, quite frankly, want to send a message contrary to what we’ve seen in Iowa and New Hampshire,” he said. “Because people are disappointed that those two states are viewed as speaking for the rest of the Democratic Party.”

Mr. Biden’s campaign, in turn, is making clear that South Carolina counts: Even as they face a financial strain following his lackluster early performances, Biden officials are pouring money into a state they hope can revive his candidacy.

On Wednesday, they placed nearly $825,000 worth of advertising on South Carolina’s airwaves.

Still, for Mr. Biden, it is difficult to run on a message of electability after opening the primary season with fourth- and fifth-place finishes. Those weak performances have sent him tumbling in the polls and underscored longstanding rules of political gravity in presidential primaries: Candidates cannot assume that their momentary strength in states voting later in the calendar can withstand early struggles.

“Let’s be honest; he was the vice president under the first African-American president so his early name recognition was really high and that lifted his numbers,” said John King, a state lawmaker who recently endorsed Mr. Steyer.

The heightened stakes have made other challenges more apparent, including the sometimes awkward fit between Mr. Biden and a new generation of young, black elected officials who are sweeping the South. Compared with Mr. Clyburn’s generation, this group is less moved by arguments of deference and the chummy collegiality of beltway politics. Instead, they view themselves as ambitious insurgents.

One of the up-and-comers, Mr. Moore, ticked off a list of what he views as blemishes on Mr. Biden’s record that should be barriers for black voters: Mr. Biden’s past support for crime bills that some experts argue resulted in harsh sentences for black offenders; his treatment of Anita Hill during Clarence Thomas’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing; and his eulogy for Strom Thurmond, the state’s onetime Dixiecrat senator.

“Joe Biden wasn’t selected as a running mate for Barack Obama because he was a civil rights activist,” said Mr. Moore, who had supported Senator Kamala Harris before she withdrew. “It was because he was a safe white choice.”

Mr. Biden has caused some of his own problems. During a private meeting with prominent black mayors in Georgia last year, according to three people with direct knowledge of the gathering, he caused a stir when answering a question about education reform. Mr. Biden said one problem black communities face is that the “parents can’t read or write themselves,” a remark that shocked and frustrated many in the close-knit group.

In a statement, Mr. Biden’s campaign said he was seeking to reference his own experience.

“The Vice President regularly talks about how his father’s experience has shaped the way he feels about and views the relationship between parents and their children’s learning,” the statement said.

As he works to shore up his support here, Mr. Biden must rely on components of his campaign that were never the strongest. Mr. Biden’s fund-raising organization, for instance, was never robust in South Carolina and throughout areas of the South with heavy black populations.

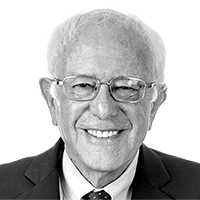

There have also been hints in recent polls that Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont is making inroads, and several black voters interviewed Wednesday said they liked Mr. Sanders for different reasons.

“He just seems genuine about what he is saying,” said Lashawndra Thompson, a 41-year-old house cleaner, as she waited at a downtown bus stop. Ms. Thompson said that Mr. Biden would be her second choice.

Alexis Davis, an 18-year-old from Greenville who is a student at the University of South Carolina, said she was attracted to Mr. Sanders’s policy agenda. “He’s trying to make it cheaper for people to go to college,” she said as she walked to class.

Mr. Sanders has also picked up the endorsements of several key African-American lawmakers.

“The things Sanders talked about four years ago — education, health care, and $15 an hour — the Democratic Party has now gravitated toward his issues,” said Representative Terry Alexander of Columbia, who is also serving as a consultant to Mr. Sanders’s campaign.

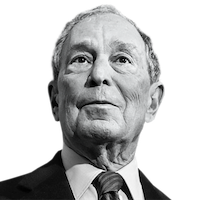

Outside of South Carolina, Mr. Biden must contend with the expanding efforts of Michael R. Bloomberg, the former New York City mayor, who is not competing here but is spending heavily across the South and is expected to be a major player in Super Tuesday states such as Alabama, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Mr. Bloomberg’s support from black voters rose significantly in the Quinnipiac national poll that showed Mr. Biden declining.

The mayor of Columbia, Stephen Benjamin, who shocked many when he became one of Mr. Bloomberg’s first endorsers, said he chose not to endorse Mr. Biden because “he couldn’t raise money, he didn’t have grass-roots energy, and he didn’t have a strong and consistent message.”

“The polls are accurate, the V.P.’s support is eroding very fast and eroding what was supposed to be his firewall,” Mr. Benjamin said.

The biggest beneficiary of Mr. Biden’s softened support here appears to be Mr. Steyer. A Fox News poll in January found Mr. Steyer’s support in South Carolina increasing to 15 percent, putting him in second place behind Mr. Biden.

Jalen Elrod, a vice chair of the Greenville County Democratic Party, who also endorsed Mr. Buttigieg on Wednesday, said that in the last month he had changed his characterization of Mr. Biden from a “strong front-runner to a weak front-runner,” with his decline being compounded by the rise of Mr. Steyer.

“I was in the barbershop,” he said, “and everyone was like, ‘I’m kind of interested in this Tom Steyer guy. He seems pretty cool.’”

Much of Mr. Steyer’s strength is tied to his heavy spending in South Carolina, where he has dominated advertising on television, Facebook and in printed fliers distributed to homes.

But in addition to his wave of advertising, and payments to some leaders he has retained as advisers, Mr. Steyer has gained strength in the black community by speaking bluntly about racial injustice, some Democrats said.

Mr. King, who had initially backed Senator Cory Booker, said he had not planned to pick another candidate before the primary until he attended a meeting in his district with the California billionaire this week.

“I was in a room where most of the folks there were white, and Tom Steyer didn’t shy away from conversation about racism and reparations and how we heal the country,” Mr. King recalled.

Clay Middleton, a well-known South Carolina operative and a former senior adviser to Mr. Booker’s campaign, said most of Mr. Biden’s South Carolina supporters had expected a top-three finish in the first two states. It was not just that the campaign has struggled, he said, but that it has failed to meet even those lowered expectations.

“They’ve ceded ground,” Mr. Middleton said. “If they finished top three in Iowa and it didn’t linger, I think they could have turned the page and moved on.”

“I don’t know if the V.P. has the infrastructure,” he added. “A win in South Carolina would help in other Southern states — but he has to win.’’

Katie Glueck contributed reporting from New York.

-

-

- See detailed maps that show where Bernie Sanders won. Pete Buttigieg finished second in a close race, with Amy Klobuchar firmly in third.

-

-

- Learn more about the Democratic presidential contenders.

Joe Biden

Michael R. Bloomberg

Pete Buttigieg

Tulsi Gabbard

Amy Klobuchar

Bernie Sanders

Tom Steyer

Elizabeth Warren

-