Vox writers are making the best case for the leading Democratic candidates — defined as those polling above 10 percent in national averages. This article is the first in the weekly series. Vox does not endorse individual candidates.

The case for Bernie Sanders is that he is the unity candidate.

The Vermont senator is unique in combining an authentic, values-driven political philosophy with a surprisingly pragmatic, veteran-legislator approach to getting things done. This pairing makes him the enthusiastic favorite of non-Republicans who don’t necessarily love the Democratic Party, without genuinely threatening what’s important to partisan Democrats. If he can pull the party together, it would set him up to be the strongest of the frontrunners to challenge President Donald Trump.

Sanders breaks from the pack in constructive ways on foreign and monetary policy, where the president has an unusual amount of freedom to act. And in the legislative arena, where any president is going to be sharply constrained, he stands the best chance of getting the left on board with the sure-to-be-disappointing compromises that will be necessary to advance the ball at all on important issues.

Most of the fears about Sanders expressed by Democratic insiders — fears that have trickled into much of the mainstream media coverage of his campaign — are better understood as disputes with his followers than as real problems with the man himself.

His extremely online loyalists (themselves only a minority of his supporters, as with any candidate) tend to be both highly ideological and highly antagonistic. Some, including younger supporters, seem to lack a broader perspective on events. They are unrealistically optimistic about what a Sanders administration could achieve, unreasonably down on Sanders’s rivals, and simply lack appreciation of how small the differences within the Democratic field are, especially compared with the gaping void between essentially all Democrats and all Republicans under modern polarized conditions.

That said, a primary is about picking a nominee, not about picking whose cheering chorus you find most congenial on Twitter. Sanders has good ideas on the topics in which the choice between Democrats matters most, he has a plausible electability case, he’s been a pragmatic and reasonably effective legislator, and his nomination is, by far, the best way to put toxic infighting to rest and bring the rising cohort of left-wing young people into the tent — for both the 2020 campaign and the long-term future.

Sanders is more banal than people think

Much of Sanders’s campaign rhetoric appears to suggest a wildly naive or uninformed understanding of how the American political system operates. He says we’ll completely transform the health care system and pass a massive Green New Deal and eliminate all student debt, all while making college free, increasing the minimum wage, enormously boosting spending on K-12 education, and overhauling the immigration system — and there’s a sweeping housing plan in there to boot.

These stances animate Sanders’s hardcore supporters, who turn his rivals’ understandable reluctance to sign on to a patently unrealistic series of promises as a litmus test.

To veterans of Beltway politics, or simply folks who’ve been around long enough and watched cycles of exaggerated hopes followed by disappointments, this can be troubling. Would a President Sanders really think that if he just bangs the table loudly enough, a “political revolution” will allow for a top-to-bottom restructuring of the American health care system? Would he reject feasible paths in favor of insisting on ideas that can’t pass?

The worry that Sanders would run an ineffective White House if he won in November is a much more reasonable fear than is vague annoyance at his rhetoric.

The good news is that Sanders is someone who’s served on Capitol Hill for nearly 30 years, not a 20-something, far-left hardliner with a red rose on his Twitter bio. Sanders has sometimes staked out lonely, courageous stands (against the Iraq War or the Defense of Marriage Act, which barred same-sex couples from enjoying the same federal benefits as married couples). But he’s never pulled a Freedom Caucus-type stunt and refused to cast a pragmatic vote in favor of half a loaf.

Sanders has always talked about his blue-sky political ideals as something he believed in passionately, but he separated that idealism from his practical legislative work, which was grounded in vote counts. He voted for former President Barack Obama’s Children’s Health Insurance Program reauthorization bill in 2009, and again for the Affordable Care Act in 2010. He voted for the Dodd-Frank bill and every other contentious piece of Obama-era legislation.

He sometimes cast protest votes against bipartisan bills that sailed through Congress with huge majorities (like the lame-duck tax-and-stimulus deal the White House reached with congressional legislators at the end of 2010), but whenever his vote was needed to incrementally advance some progressive cause, it was there.

Indeed, this has been somewhat forgotten in the wake of the 2016 primary campaign: While Obama was in the White House, it was Sen. Elizabeth Warren who attracted the ire of administration officials and congressional leaders by occasionally spiking executive-branch nominees or blowing up bipartisan deals.

The policy area in which Sanders has had the most practical influence is veterans-related issues, as he chaired the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee for a two-year span, during which Congress enacted substantive reform to the veterans’ health system.

Given the objective constellation of political forces at the time, this required bipartisan support, so Sanders (working mainly with Republican Sen. John McCain) produced a bipartisan bill that, in exchange for a substantial boost in funding, made some concessions to conservatives in creating “private options” for veterans to seek care outside of the publicly run Veterans Health Administration.

It’s fine if you want to be annoyed that Sanders’s self-presentation as a revolutionary who will sweep all practical obstacles aside is at odds with his reality as an experienced legislator who does typical senator stuff in a typical way. But there’s no reason to be worried that Sanders is a deluded radical who doesn’t understand how the government works.

Sanders is right on a few key topics

The truth is that on most issues, the policy outputs of a Sanders administration just wouldn’t be that different from those of a Joe Biden or Pete Buttigieg administration. Whether a new president promises continuity with Obama or a break with neoliberalism, the constraints will realistically come from Congress, where the median member is all but certain to be more conservative than anyone in the Democratic field.

But Sanders does have some ideas with unique appeal, particularly on foreign policy.

The evidence is overwhelming that most primary voters don’t particularly care about foreign policy, and consequently, it isn’t discussed very much during the campaign. That’s a shame; it’s an important topic on substance, and it’s also the area in which the president has the most flexibility. Presidents are constrained in their conduct on foreign policy by dozens of institutional and political factors, but less so than elsewhere.

Whatever Obama said or did or wanted, there’s no way he could have gotten Medicare-for-all enacted. But he could have intervened more forcefully in Syria had he desired to do so, just as he could have avoided intervening in Libya.

It’s clear that Sanders has a real desire to challenge aspects of the bipartisan foreign policy consensus, compared with the rest of the field. He’s much more critical of Israel than most people in national politics, he’s a leading critic of the alliance with Saudi Arabia, and he’s aligned himself with the Latin American left in ways that Warren doesn’t.

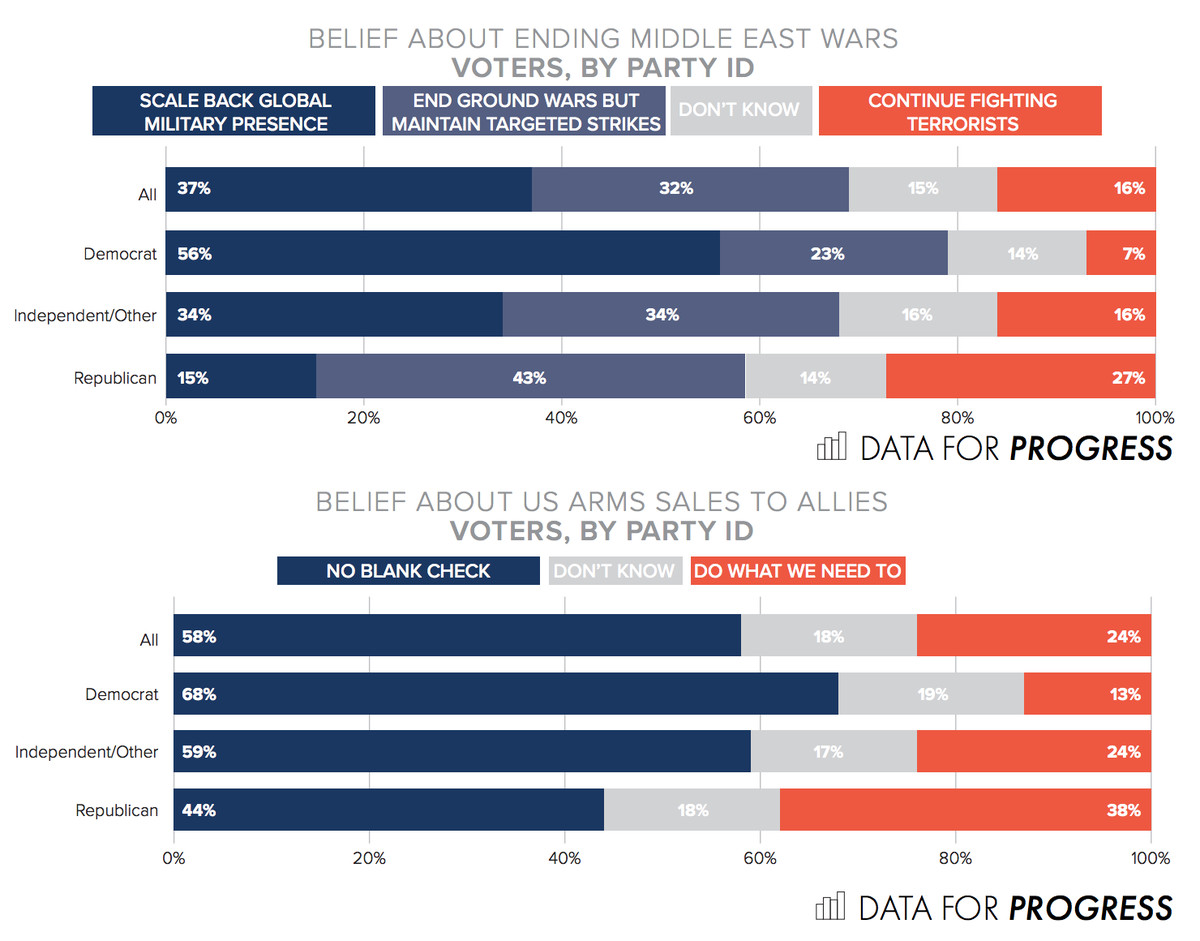

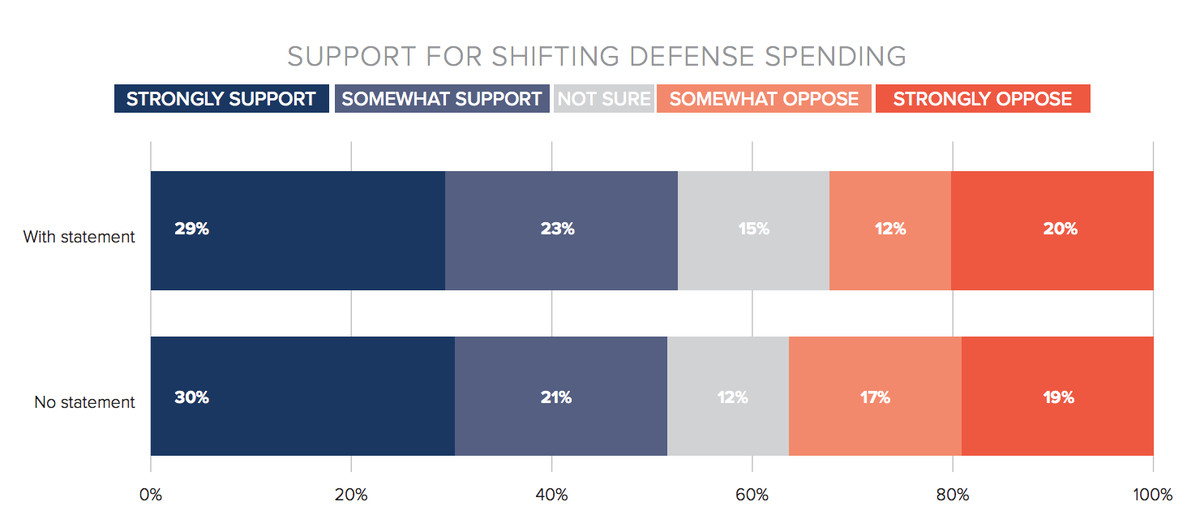

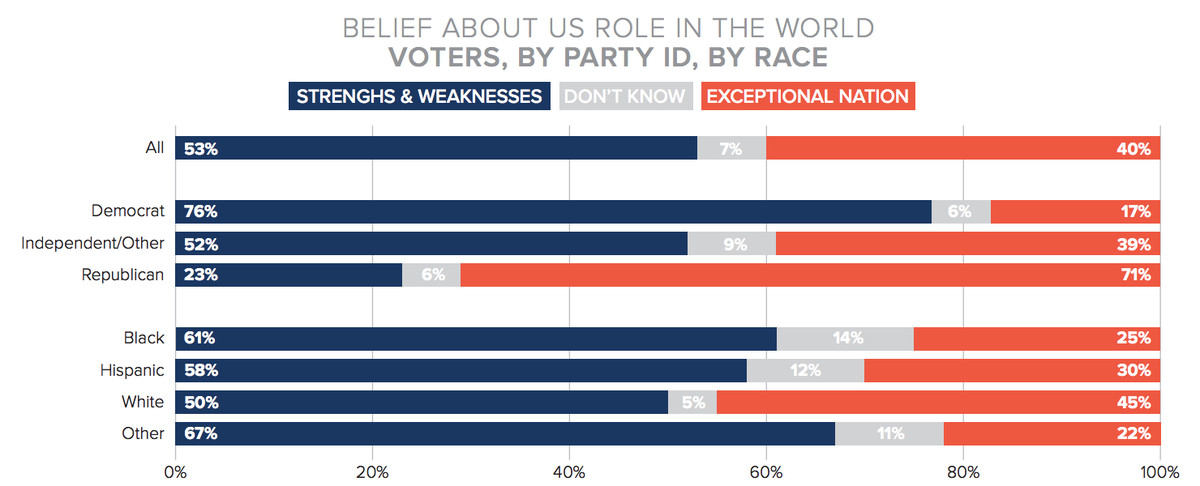

These ideas are coded as “extreme” in Washington, where there’s significant bipartisan investment in the status quo. But polls show that most voters question the narratives of American exceptionalism, favor a reduced global military footprint and less defense spending, and are skeptical of the merits of profligate arms sales.

In practice, essentially every president ends up governing with more continuity than his campaign rhetoric suggested (Trump hasn’t broken up NATO; Obama never sat down with the leadership of Iran), so the differences are likely to be more modest than the rhetorical ones.

But differences are welcome and needed. The misbegotten invasion of Iraq should have, but largely didn’t, shake up the establishment “blob” that’s obsessed with pursuing US military hegemony and endless entanglements in the Middle East. Recent reporting by the Washington Post revealed that military and political leaders across three administrations have been lying to the public about the course of the war in Afghanistan — and it barely made a dent in domestic politics.

Nobody should have illusions about Sanders somehow unilaterally ushering in a bold new era of world peace, but he is by far the most likely person in the race to push back against expansive militarism — and that’s worth considering.

Foreign policy isn’t the only hidebound institution he is poised to shake up, either.

Pro-worker monetary policy could make a real difference

Monetary policy attracts even less attention in the primary than does foreign policy. But the Washington Post did survey the candidates’ views on interest rates when it asked whether the Federal Reserve’s current rates are too high. The results were fascinating.

Buttigieg, Biden, and Warren all demurred, citing the dogma that the Federal Reserve should stay independent of politics (though Warren, to her credit, made a strong statement in a subsequent speech on the economy about the need to emphasize full employment).

Sanders, by contrast, offered a clear statement, saying he “disagreed with the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates in 2015-2018” because “raising rates should be done as a last resort, not to fight phantom inflation.”

Sens. Cory Booker and Michael Bennet, two minor candidates who aren’t really seen as Sanders’s fellow travelers when it comes to ideology, had somewhat similar things to say. “Historically, the Federal Reserve raises interest rates when the economy has reached full employment,” Booker said, adding that “our economy’s not there yet.” Bennet nodded toward independence before saying that the Fed “has often fallen short of its full employment mandate, which has harmed workers, especially those trying to make ends meet.” He also said that his appointees to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors “will prioritize the employment mandate and consider every tool available to meet that mandate.”

Unfortunately, this is a niche issue many people don’t care about. Almost everyone does and should care about “the economy,” though, and the main government institution responsible for the state of “the economy” is the Fed.

What’s more, this is a particularly important issue precisely because it’s a little bit obscure. Any Democratic president’s Environmental Protection Agency director will come from the universe of “people the main environmental groups like and for whom moderate senators are willing to vote,” because that’s how politics works. But there are no strong interest groups that lobby around monetary policy.

A president who wants to install well-qualified people inclined to side with Sanders/Bennet/Booker will probably be able to do so, but a president who doesn’t care (like Obama) will probably end up appointing people whose views are all over the map (which is indeed what happened with Obama).

These aren’t the only two issues in America that matter, but they’re the main ones in which different nominees are likely to lead to different results. Almost everything that’s currently being debated, by contrast, is pointless.

Sanders wins elections

If you were designing an electability candidate in a lab, you would not come up with Bernie Sanders. You’d probably come up with someone like moderate Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, who recently dropped out of the race after receiving essentially no public support or donations. Bullock turned out to be poorly suited to a modern primary process that is heavily weighted toward a candidate’s skill at attracting attention, but his proven track record of winning in a conservative state gave me confidence that he’d be an effective nominee, had that somehow happened.

Perhaps the diplomatic and popular Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar would be it. Minnesota is not Montana, but Klobuchar consistently overperforms baseline partisan fundamentals in a state that’s only modestly Democratic-leaning. Yet she’s trailing the top four in the Democratic field.

The reality is that four candidates — Sanders, Biden, Buttigieg, and Warren — have pulled away in a year in which Democrats say they are focused on electability. All of these candidates have obvious weaknesses. Of the crew, Sanders has arguably the best case to make for electability. His electoral track record is strong, whereas Warren’s is weak, Buttigieg’s is almost nonexistent, and Biden’s is mostly lacking in relevant information.

Winning races in Vermont is less impressive than winning them in Montana. And there are certainly plenty of left-wing Democrats who win while underperforming simply because they hold safe seats (Warren fits that mold), as well as plenty of moderate Democrats who overperform in tough races even while losing (former Missouri Sen. Claire McCaskill is a good example).

But Sanders appears to be a candidate who overperforms in easy races. He consistently runs ahead of Democratic presidential nominees in his home state, which suggests he knows how to overcome the “socialist” label, get people to vote for him despite some eccentricities, and even peel off some Republican votes.

Sanders first got to Congress by winning a tough three-way race in 1990, when Vermont was an only slightly blue-leaning state. He went on to consistently run ahead of Democratic presidential campaigns as a candidate for Vermont’s at-large seat in the US House of Representatives:

- In 1992, Sanders got 58 percent to Bill Clinton’s 46 (it was a strong state for presidential candidate Ross Perot, but Bernie also faced a “third-party” challenge from a Democrat).

- In 1996, Sanders got 55 percent to Clinton’s 53 percent.

- In 2000, Sanders got 69 percent to Al Gore’s 51 percent.

- In 2004, Sanders got 67 percent to John Kerry’s 59 percent.

- Sanders got elected to the Senate in 2006, so he wasn’t on the ballot in 2008 or 2016. But in 2012, he won 71 percent to Obama’s 67 percent.

This is not definitive proof of Sanders’s skills — over the past 20 years, these haven’t really been vigorously contested races. Yet because those weren’t tough races, it would have been easy for Vermonters who had doubts about Sanders to cast meaningless protest votes for his opponents.

Sanders also appears to be able to make lemonade out of the whole “not officially a Democrat” thing by getting the votes of some non-Republicans who backed Perot in the 1990s and, more recently, other third-party candidates such as Jill Stein, Ralph Nader, and Gary Johnson. Indeed, one noteworthy thing about Sanders is that in head-to-head polling matchups against Trump, he tends to do better than you’d expect simply by looking at his favorable ratings.

Sanders’s popularity seems to be concentrated among certain blocks of persuadable voters (likely those considering a third-party vote), while a chunk of those who disapprove of Sanders are hardcore partisan Democrats who don’t like his lack of party spirit but will vote for him anyway.

At times Sanders embraces unpopular positions, like passing broad tax increases to finance Medicare-for-all or decriminalizing unauthorized entry into the United States. Compared with some hypothetical other Democrat, this could make him a weak choice. But he’s running against a field that also takes unpopular positions. It’s worth noting that even Biden has come out in favor of opening government insurance programs to the undocumented, allowing taxpayer funds to subsidize abortions, and ending the death penalty.

Bernie is a unifying choice

At the end of the day, Sanders’s record is not nearly as scary as many establishment Democrats fear. His “revolution” rhetoric doesn’t make sense to me, but he’s been an effective mayor and legislator for a long time, and he knows how to get things done — and how hard it is to get them done.

Some of his big ideas are not so hot on the merits, but it’s not worth worrying about them because the political revolution is so unrealistic. And on a couple of issues where the next president will probably have a fair amount of latitude, Sanders breaks from the pack in good ways. He’s perhaps not an ideal electability choice, but his track record on winning elections is solid and his early polling is pretty good. There’s no particular reason to think he’d be weaker than the other three top contenders, and at least some reason to think he’d be stronger.

A Sanders presidency should generate an emphasis on full employment, a tendency to shy away from launching wars, an executive branch that actually tries to enforce environmental protection and civil rights laws, and a situation in which bills that both progressives and moderates can agree on get to become law.

That’s a formula the vast majority of mainstream Democrats should be able to embrace.

Lots of moderate Democrats nonetheless find it annoying that Sanders and some of his followers are so committed to painting mainstream Democrats in such dark hues. And it is annoying! But annoying people won’t stop being annoying if he loses the nomination. If anything, they will be more annoying than ever as some refuse to get enthusiastic about the prospect of beating Trump. But if Sanders wins, partisan Democrats who just want to beat Trump will magically stop finding Bernie superfans annoying — the causes will be aligned, and the vast majority of people who want Trump out of the White House can collaborate in peace.

That leaves us where we started. The president really does have a good deal of latitude in conducting national security policy. If it’s very important to you that the US maintains a hawkish military posture in the Middle East, that’s a good reason to worry a lot about Sanders.

But most likely, a Sanders presidency will simply mean that young progressive activists are less sullen and dyspeptic about the incremental policy gains that would result from any Democrat occupying the presidency. It’ll also mean a foreign policy that errs a bit more on the side of restraint compared with what you’d get from anyone else in the field, as well as an approach to monetary policy that errs a bit more on the side of full employment. That’s a pretty good deal, and you don’t need to be a socialist to see it.