Judging solely by President Donald Trump’s recent diatribes, mail-in voting would seem to have become one of the nation’s most partisan flashpoints. But at the state level — where elections are actually administered — there’s little disagreement.

Instead, most state officials are ignoring partisanship and quietly laying the groundwork for an effective, mail-heavy election, including in those states led by Republicans.

“State election directors are aware of that conversation, but I think they’ve got their heads down,” said Ben Hovland, the chair of the federal Election Assistance Commission, which regularly videoconferences with state election chiefs and helps advise them in detail on how to deal with a surge of mailed ballots. “They focus on the job at hand. There’s more than enough to do without worrying about political fights that are taking place.”

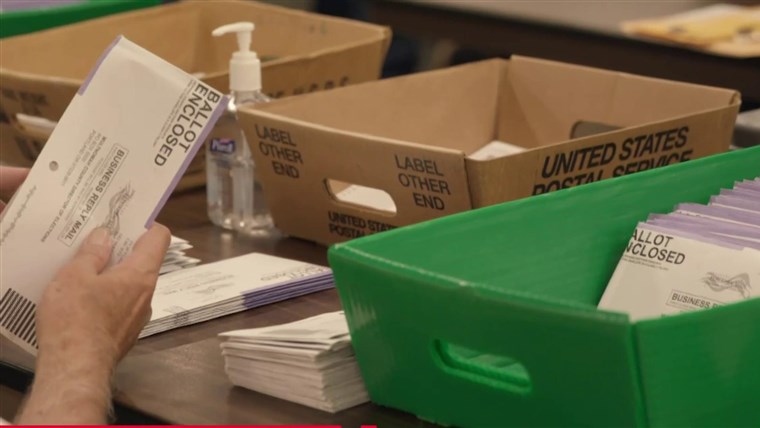

All but four states now offer every eligible voter the option to mail in their ballot, according to a new survey from the Open Source Election Technology Institute, a nonprofit that researches election technology. NBC News has collaborated with the institute since 2016 to monitor U.S. election-technology and voting issues.

Of the states offering mail-in options, leadership is almost equally split: 24 have Democratic governors and 22 Republican.

The findings reflect a significant contrast between the politicized rhetoric of mail-in voting in national politics and the reality faced by the states tasked with running elections during the coronavirus pandemic. Regardless of the national partisan conversation, states are methodically working to get their residents to vote while trying to minimize their potential exposure to the coronavirus.

That’s a change from just a few months ago. At the beginning of the year, states were divided on voting by mail. While five western states were already on an all-mail system — three headed by a Republican governor or chief election official — 31 were “no-excuse” absentee states, meaning any eligible voter could apply for a mail-in ballot if they wanted. Sixteen didn’t yet offer that option.

But since the pandemic started, 12 of the states that required a reason for a mail-in ballot — seven under Republican governors, five under Democrats — have found a way around that restriction for the primary or general elections, whether through reexamining state law, agreements with state attorneys general, or a governor’s order. And nearly all states have invested resources into new methods of encouraging voters to mail their ballots instead of physically visiting a polling place, like pre-emptively mailing out applications to all registered voters.

“We had to make the decision to make absentee balloting as our priority. That’s when I made the announcement we were going to find the funds and were going to mail out the request forms to every voter,” said Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate, a Republican and the current president of the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS). “That’s the bully pulpit I’m going to be standing on this primary. Those changes are what I’ve had to work hard at communicating.”

“The frustration for many of us in my role as the NASS president is I would prefer the politicians leave the debate on us voting by mail,” Pate said. “It doesn’t help when I have some of the politics that’s going on.”

State election chiefs are in broad agreement about expanding voting by mail this year, with the main point of contention being whether the change should be permanent or confined to the duration of the pandemic, which particularly gives some Republicans concern. The public seems to agree: An NBC poll found that 58 percent of Americans support voting by mail, with an additional 9 percent agreeing if it’s limited to just 2020.

Trump in particular has repeatedly spread a number of falsehoods about voting by mail, tweeting recently that it is a “scam” that’s “ripe for fraud” and would lead to the election being “rigged.”

Last week, Trump falsely accused Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat, of pre-emptively mailing out ballots, rather than ballot applications, to millions of Michiganders. He later deleted and re-sent a tweet that corrected that error, but repeated the unfounded claim that Michigan’s encouragement of voters to mail their ballots meant it was going down a “Voter Fraud path!” He also falsely claimed that Benson’s mailing out ballot applications was illegal for a secretary of state.

While no Republican state election chief has publicly and directly contradicted Trump, some have reaffirmed their support for voting by mail, like Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger in a press release the same day Trump tweeted about Benson.

“The fact and the irony is that my Republican colleagues in other states, like West Virginia, Nebraska, and Iowa, and Georgia were doing the exact same thing,” Benson said. “And I knew that because we talk regularly.”

Trump has previously falsely and repeatedly insisted that “millions” of voters cast fraudulent ballots in the 2016 election, even going so far as to create a voter fraud commission that disbanded in 2017 after coming up empty-handed.

Election fraud does happen — but only occasionally. In one case, a Michigan clerk named Sherikia Hawkins, a Democrat, was accused of trying to change the number of absentee ballots cast in the 2018 election after another clerk noticed a discrepancy in a voter file. Benson herself helped announce the charges. Hawkins is awaiting trial.

“Voter fraud is infinitesimal. It is extremely rare, but when it does happen we have the tools in place to catch it, which is precisely what we did,” Benson said.

Some state election officials object to congressional Democrats who want to give every American the permanent right to vote by mail if they choose, forcing states that don’t normally allow no-excuse absentee ballots to do so.

“I would like them to let us election professionals do our jobs,” Pate said. “If they want to help — and I’m speaking to Congress — the funding is extremely helpful, because we are faced with challenges right now where most states do not have the money earmarked, and state treasuries are going to take big hits.”

Kim Wyman, a Republican and the secretary of state of Washington — a vote-by-mail state since 2011 — said her frequent calls with other state election chiefs aren’t debates about the merits or drawbacks of voting by mail. Rather, they’re about the shift to more mailed ballots, like whether states should have voters sign the outside of the envelope when they mail in a ballot, because mail sorters can automatically take a picture.

“One state I talked to, they don’t have those signatures digitized. How are you going to process those if you suddenly increase your volume by 50 percent?” Wyman said.

That’s the mindset state election officials in general are bringing to the job, Benson said.

“All these intricacies of running elections have no partisan element to them at all. And we all see that,” Benson said. “Those of us on the front lines, actually administering democracy, we see that.”