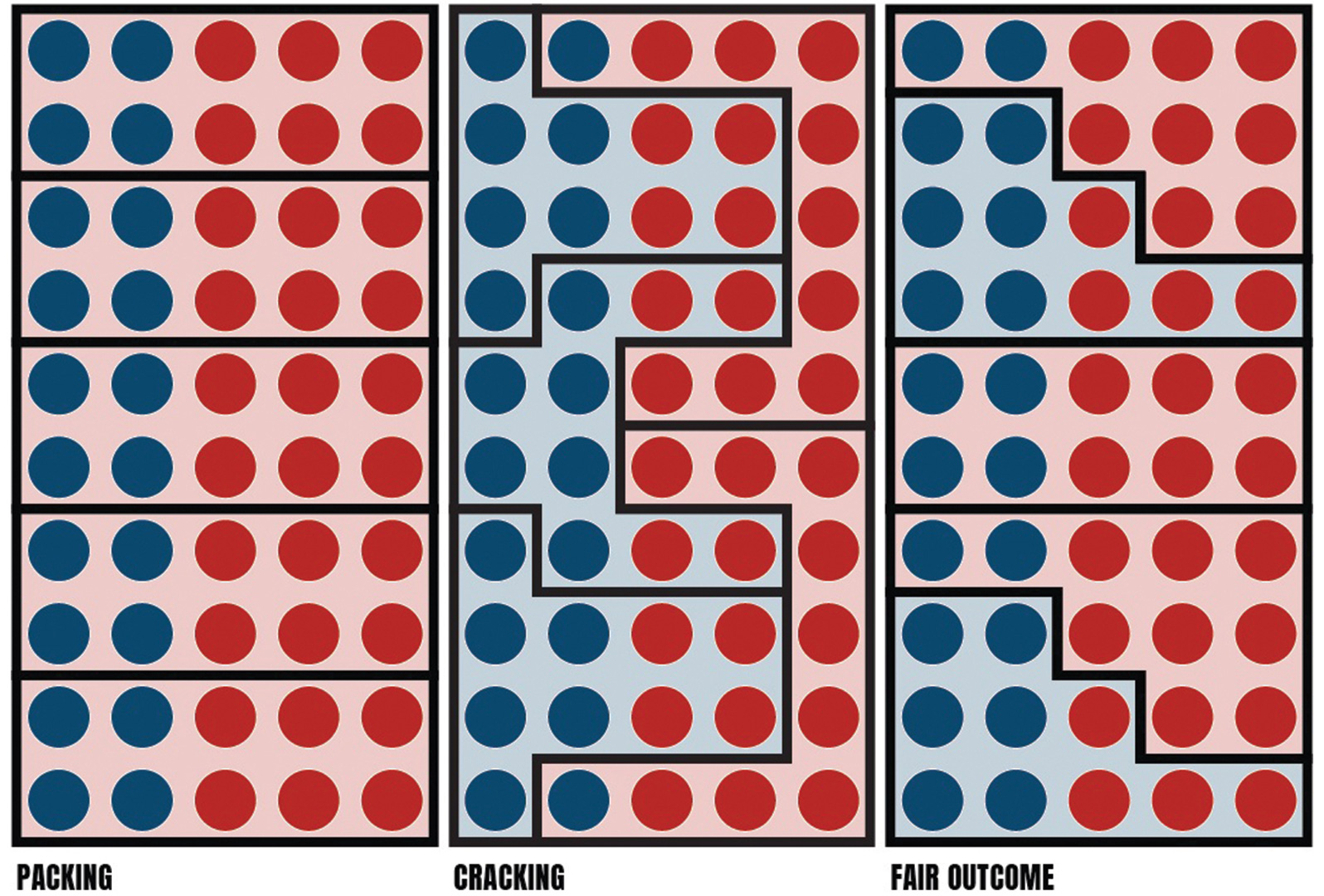

This graphic shows three ways to create five legislative districts for a population that is 60% red and 40% blue. In the left image, demonstrating “packing,” red wins all districts. In the middle image, demonstrating “cracking,” red wins two districts and blue wins three districts. In the right image, red wins three districts and blue wins two. This outcome is fair, according to a report from Arkansas Public Policy Panel, because red has 60% of the population and wins 60% of the districts. (Arkansas Public Policy Panel)

This graphic shows three ways to create five legislative districts for a population that is 60% red and 40% blue. In the left image, demonstrating “packing,” red wins all districts. In the middle image, demonstrating “cracking,” red wins two districts and blue wins three districts. In the right image, red wins three districts and blue wins two. This outcome is fair, according to a report from Arkansas Public Policy Panel, because red has 60% of the population and wins 60% of the districts. (Arkansas Public Policy Panel)LITTLE ROCK — A pair of advocacy groups wants Arkansans to understand the legislative redistricting that will follow this year’s U.S. Census, as well as the potential pitfalls of the process.

Sister organizations Arkansas Public Policy Panel and Arkansas Citizens First Congress this week published a report they hope will raise public awareness of how Arkansas’ state and federal political districts come to be, including through various forms of gerrymandering.

The groups support instituting a nonpartisan commission to make redistricting decisions, Policy Director Kymara Seals said during a news conference Wednesday. But the report, titled “Redistricting & Gerrymandering in Arkansas: How Our Districts Got Their Shapes,” stops short of making any specific recommendations.

The report walks readers through the steps involved in redrawing districts: counting the population by means of the Census; reapportionment, determining how many people will be represented by each district; and redistricting, the reshaping of legislative districts to reflect changes in population numbers.

But the bulk of the report explains gerrymandering, “the intentional manipulation of legislative district lines in order to advantage one group (and therefore disadvantage another group) in future elections.”

Gerrymandering creates four “core challenges” to democracy, according to the report: biased representation, noncompetitive elections, growing political polarization and an increase in costly legal challenges.

Three kinds of gerrymandering are the most common. Partisan gerrymandering involves a political party drawing legislative lines to attain an unfair advantage. Racial gerrymandering sets out to diminish the voting power of minorities. Nonpartisan incumbent gerrymandering seeks to keep certain politicians in office.

Less common is bipartisan gerrymandering, in which political parties work together to manipulate district boundaries to ensure mutually beneficial electoral outcomes.

Partisan gerrymandering often employs methods called cracking and packing.

Cracking separates the opposing party’s voters into many different districts, allowing the preferred party to win elections in several districts against a divided opposition.

Packing results in the opposing party’s voters being pushed into one or a few districts.

“The majority party surrenders the packed district to the opposition party, but the majority party can likely win the other districts,” the report states.

The report goes on to explain a redistricting case study, redistricting requirements in Arkansas, geographic challenges for redistricting in the state and reforms enacted in other states, including various forms of commissions meant to ensure fairness.

In Arkansas, the state General Assembly draws U.S. Congressional District lines.

A body called the Board of Apportionment — comprising the governor, the secretary of state and the attorney general — redistricts Arkansas’ 35 Senate and 100 House districts. Arkansas is one of only three states to use such a panel of politicians to decide redistricting.

An organization called Arkansas Voters First is trying to add an item to November’s general election ballot that, if approved by voters, would create an independent redistricting commission. But the ballot initiative is mired in a legal battle over the validity of petitions calling for it.

The proposal “would shift the authority for redrawing the boundaries of legislative districts from the state Board of Apportionment to a nine-member independent commission comprising three Democrats, three Republicans and three independents.

“The proposal also would shift authority for redrawing the boundaries of the congressional districts from the Legislature to the nine-member commission,” according to an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette report.