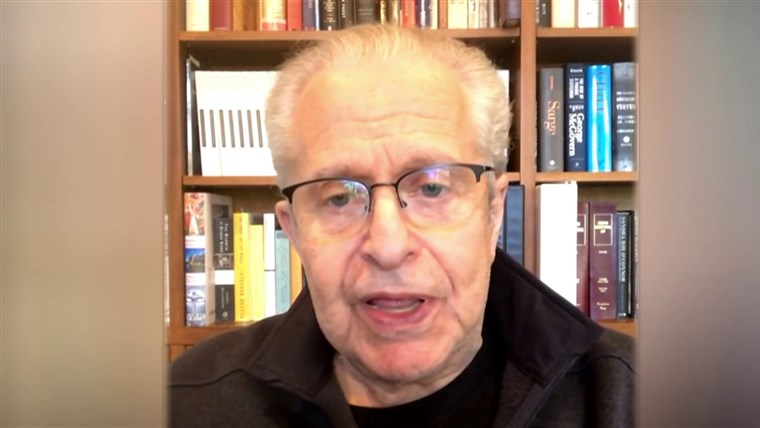

When Peterson Zah attended the Phoenix Indian School as a youth, teachers there instructed students on the importance of voting.

At the time, the majority of Native people in Arizona didn’t have that right.

“Fast forward years to when we were trying to carry what we were taught, there was all kinds of blocks,” said Zah, 82.

By the time he was of voting-age, voting rights were legally conferred, but, in practice, Native Americans — as well as other minorities in the state — remained disenfranchised en masse by a series of discriminatory voting practices, policies and requirements.

Zah, now 82, has spent the majority of his life working to remove those blocks. He grew up on the Navajo Nation in the 1940s and later become the chairman and first president of the Navajo Nation following years at civil rights organizations.

“These rights weren’t always there in the form that they’re in now,” he said. “Many people had to do the hard work to fight for these rights and people need to know about that history.”

The racist history of Arizona blocking or diminishing Latino, Black and Native people’s ability to participate in the political process is long, dating back to the state’s territorial period, and features tactics reminiscent of the Deep South.

The state employed a strict literary test for voter registration for more than 60 years and as recently as 2013 was one of only 11 states singled out by a section of the Voting Rights Act due to a long record of suppressing minority voters.

And some say the state and nation are now in the midst of a “second generation” of discriminatory voting practices — one defined by strict voter ID laws and polling location closures, among other measures, that have taken the place of literacy tests or voter intimidation.

Earlier this year, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned two Arizona laws that made it more difficult to cast a ballot, noting the laws’ “discriminatory intent” and citing the state’s “long history of race-based voting discrimination.”

Those laws were passed after the U.S. Supreme overturned parts of the Voting Rights Act in 2013. They remain in place for now, though, as the state appealed the ruling.

Raul Macias, a voting rights counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice, said some states, including Arizona, used the Supreme Court’s action as an opportunity to impose new restrictions that have disparate impacts on minority voters.

As a swing state in the 2020 election, Arizona could be a deciding factor in the future of national politics. And experts say minority voters likely will tip the scales.

Territorial Legislature implements literacy test for voter registration

Efforts to erode the political power of minorities began long before Arizona achieved statehood in 1912.

“Early territorial politicians acted on the belief that it was the ‘manifest destiny’ of the Anglos to triumph in Arizona over the earlier Native American and Hispanic civilizations,” wrote David Berman, a political science professor at Arizona State University, in an expert report prepared for the case the 9th Circuit ruled on earlier this year.

The land that now makes up most of modern-day Arizona was ceded to the United States from Mexico in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which marked the end of the Mexican-American War. Pursuant to the treaty, the United States conferred citizenship to the roughly 100,000 Hispanics who remained in the territory.

Native Americans at the time were considered members of their sovereign tribal nation, not U.S. citizens. So when citizenship and voting rights were extended to emancipated slaves after the Civil War, Indigenous people remained disenfranchised.

The early Arizona Territorial Legislature, comprised largely of white settlers, passed an array of discriminatory laws.

Though, perhaps most notably, they imposed a statute in 1909 that required an English literacy test as a prerequisite to voter registration, following in the footsteps of multiple Southern states that implemented literacy tests in the late 19th century.

The intentions for the law were explicit, Berman said: they were seeking to block the “ignorant Mexican vote,” quoting a letter between Arizona politicians at the time.

A year later, when the federal government authorized Arizona to draft a state Constitution, Congress specifically said the newly adopted literacy test could not be used to block minorities from voting on the proposed state Constitution. The literacy test requirement was subsequently overturned – but not for long.

Arizona formed a constitutional convention in 1910 to begin drafting a state Constitution that, once voted on and approved by the federal government and Arizona voters, would officially qualify Arizona as a state.

All except for one of the delegates was white, according to Berman. By comparison, Hispanics made up one-third of the delegates in New Mexico, which held a constitutional convention to gain statehood the same year.

New Mexico’s Constitution as written protected citizens’ ability to participate in the political process free from discrimination on account of “race, language or color, or inability to speak, read or write the English or Spanish languages.”

Arizona’s Constitution offers a stark contrast: it includes a requirement that an individual “read, write, speak, and understand the English language sufficiently well” to hold a position in public office. That provision remains in the Arizona Constitution today.

Native Americans faced multiple barriers to vote

Following approval of the Constitution, Arizona became a state on Feb. 14, 1912.

Democratic state politicians promptly reinstated the literacy test as a prerequisite to voter registration.

County registrars did not enforce the requirement equally, Berman said, often administering white citizens easier tests or excusing them from the requirement altogether while expecting Hispanic citizens to pass without error.

As a result, some counties were left without enough voters to justify holding primaries due to large declines in voter registration.

The literacy test disenfranchised Latino, Black and — when they finally gained the right to vote — Native voters until it was repealed 60 years later, in 1972.

On top of the literacy test, Native Americans faced another barrier. More than a decade into Arizona’s statehood, most weren’t conferred as United States citizens.

Native people made up a significant proportion of the state’s population at the time, according to Patty Ferguson-Bohnee, a Native voting rights expert and director of the Indian Legal Clinic at ASU. They comprised 14.3% of the state’s population, according to the 1910 census.

“In some places, that would’ve made a huge difference in who could be elected, if they were able to participate in the political process,” she said.

The federal government blocked Native American suffrage by employing several arguments — including their residency on reservations and exemption from paying taxes — to discredit arguments for Native citizenship and voting rights, she said.

Congress eventually passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, which should have given Native Americans the right to vote in both state and federal elections. But Arizona politicians, concerned about the potential shift in power, started looking for ways to continue to suppress the Native vote.

A 1928 letter from a legal advisor to then Arizona Gov. George W.P. Hunt shows he was advised to “adopt a systematic course of challenging Indians at the time of election.”

Ahead of elections, county officials challenged individual voter registrations, claiming Native Americans were “wards of the nation” and thus ineligible to vote in accordance with the state Constitution. Two Pima County Native residents challenged their rejected voter registrations, but the Arizona Supreme Court sided with the county.

Twenty years later, at the end of World War II, Native men who had played an instrumental role in the war as code-talkers returned to find that they were still denied the right to vote back home.

Frank Harrison and Harry Austin, two men from the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, sued the state and in 1948, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled in their favor, overturning the prior decision and officially granting Indigenous Arizonans the right to vote.

But along with other minority groups, that didn’t fully happen in practice until the literacy tests were banished nearly a quarter of a century later.

Despite victories, tactics continue

Because of continued suppression, the demographics of Arizona’s registered voters didn’t change much for the next two decades despite the legal victories. Arizona systematically denied voting rights and access to minority voting-age citizens through both official and unofficial suppression tactics.

The English literacy test requirement remained the most effective obstacle to voting rights for Arizona’s Latino, Black and Native American citizens for several decades, experts say.

After the 1948 ruling in favor of Native Americans, about 80% to 90% remained disenfranchised because they could not read or speak English, according to Arizona Republic archives. In the 1960s, about half of the voting-age population of the Navajo Nation were unable to vote for the same reason, Ferguson-Bohnee said.

Those who did manage to pass the test and register to vote faced voter intimidation through the ’50s and ’60s, according to Berman.

“Intimidation of minority-group members — Hispanics, African Americans as well as Native Americans — who wished to vote was … a fact of life in Arizona,” Berman wrote in the report.

White voters would ask them to read and explain “literacy” cards with excerpts from the U.S. Constitution or spread false information, such as that voting would lead to increased taxation of native populations, hoping to “frighten or embarrass minorities and discourage them from standing in line to vote,” he said.

To make a bad situation worse, the now Republican-dominated Legislature decided to cleanse voting rolls, requiring all voting-age citizens to reregister.

The change wasn’t clearly communicated to Hispanic voters, Berman said, and it “erased years of registration drives in barrios across the state.”

Voting Rights Act provides relief

By 1965, the fight against minority disenfranchisement was long underway. But it wasn’t until peaceful protesters in Selma, Alabama were attacked by state troopers, that the federal government started taking steps toward enacting legislation designed to dismantle discriminatory voting practices and ensure the enforcement of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

The resulting piece of legislation, the Voting Rights Act, was signed into law in 1965 — 55 years ago last month.

The law recognized that race-based voter suppression was more prominent in some areas of the country, so it created a formula to identify those areas and impose stricter remedies.

Any state or locality that maintained a “test or device,” such as a literacy test, that restricted voting registration or voting and had a voter registration of less than 50% was subject to those remedies.

Those jurisdictions were required suspend the use of their test and were subject to “preclearance,” meaning all changes to voting practices needed pre-approval from the federal government.

From the start, Arizona was on that list. Three Arizona counties — Apache, Coconino and Navajo — fit the description, making Arizona one of only 11 states fully or partially covered under the 1965 formula.

The federal government amended and extended the special provisions for states with a history of discriminatory voting practices multiple times.

An amendment in 1970 also effectively created a nationwide ban on literacy tests, which Arizona promptly challenged. The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously upheld the ban, pointing toward the “serious problem of deficient voter registration” among Latino, Black and Native American citizens in the state. Though, the state’s literacy ban wasn’t officially repealed until two years later.

In 1975, the entire state became covered after the federal government broadened the coverage formula to include discrimination against “language minority groups.” Only two other states — Texas and Alaska — also were covered in their entirety.

Sean Morales-Doyle, director of the voting rights and elections program at the Brennan Center for Justice, said preclearance through the VRA was arguably the most effective remedy against civil rights violations in the nation’s history.

“It was amazingly effective at not only stopping bad and discriminatory practices from going into effect but actually stopped many jurisdictions from enacting these bad policies in the first place,” he said.

In the ’80s and ’90s, the U.S. Department of Justice blocked 17 proposed changes to voting practices in Arizona that they found to have a discriminatory effect or purpose on minority voters, with three related to statewide redistricting plans.

By the early 2000s, Bohnee-Ferguson said Native voters were turning out in record numbers. In 2000, three Native American representatives and one senator were elected to the state Legislature. Former Gov. Janet Napolitano credited her win in 2002 to the high turnout rates of Native Arizonans.

New wave of voter suppression

Despite that progress, James Tucker, a pro bono voting rights counsel for the Native American Rights Fund and Voting Rights Act expert, said there’s an ongoing national movement to make it more difficult for minority voters to register and cast a ballot. And Arizona is no exception, he said.

“People who are in power try to do everything to cling onto that, even when they aren’t the majority anymore,” Tucker said, alluding to the changing demographics in Arizona.

One of the most notorious issues for Latino and Native voters in Arizona in the past several decades was Proposition 200, the “Arizona Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act,” passed in 2004.

Enacted as an effort to discourage illegal immigration, Tucker said Proposition 200 created a significant barrier for voting-age Latinos and Native Americans to participate in elections.

The measure required all in-person voters to produce a form of identification at the polling location and proof of citizenship. The result, Tucker said, was the disenfranchisement of Native and Latino voters, who by tradition or circumstance are less likely to have the forms of identification required to vote.

Opponents challenged the requirements, citing their discriminatory effect, sparked years of legal battle. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the proof of citizenship requirement for voting in federal elections in 2013.

That same year, the U.S. Supreme Court decision retracted the section of the Voting Rights Act that created federal oversight for states, like Arizona, with a history of race-based voting discrimination. That created space for jurisdictions to pass laws that the Department of Justice may have objected to under preclearance.

Today, language continues as a barrier for minority voters in the state.

Translations of voting material have repeatedly misrepresented or mistranslated key information, researchers say.

The 2012 official Spanish-language voter pamphlet in Maricopa County provided Spanish-speaking voters with the wrong election date. The same mistake was not made in the English-language version.

For Native communities, where many languages are historically unwritten, oral assistance is required to provide voters with the same election information. Though, there are many recorded instances of translations misrepresenting what is on the ballot or not enough poll workers to make the oral translations.

Tucker said counties that don’t provide adequate oral assistance to voters do so due to a “lack of resolve” as opposed to a lack of resources.

“I think you’ll find in Arizona that there are some county recorders who do a really good job of working with the local tribes to make sure that they get those translations and have available poll workers who speak that language,” Tucker said. “But there are other counties in Arizona where that is simply not true.”

Reductions in polling locations in recent elections have also disproportionately affected minority voters.

Maricopa County reduced its number of polling sites by 70% from 2012 to 2016, requiring Latino, Black and Native voters to travel greater distances to vote, according to the 9th Circuit decision from earlier this year.

And strict voter ID laws, failure to provide translations of voter material and polling location closures are just a fraction of the ongoing barriers impacting minority voters, experts say.

In January, the 9th Circuit overturned two other laws — a 2016 ban on so-called “ballot harvesting” and the state’s policy of discarding provisional ballots of out-of-precinct voters — finding that they were enacted with discriminatory intent and disproportionately affect Latino, Black and Indigenous voters.

Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich challenged the ruling and the appeals court granted a stay, so the practices remain in place for now.

Eyes on the 2020 election

Given Arizona’s long history of race-based voter discrimination, voting rights advocates are on high alert for any discriminatory voting practices or policies, said Murphy Bannerman, deputy director of Election Protection Arizona, an organization dedicated to protecting voting rights and access in Arizona.

For the November election, she said they’re watching to ensure proper language assistance is provided, poll workers are educated on voter ID laws and all voters have access to both in-person and voting via mail.

And as there are nationwide concerns about the infrastructure to accommodate mail-in voting amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Native voting rights experts say tribal communities need to have access to in-person early and Election Day voting because many people voting on tribal land don’t have at-home mail delivery or pickup.

“Lawmakers who are making these decisions need to be cognizant that not everyone has the same access to mail or the internet or traditional forms of identification,” Ferguson-Bohnee said.

Peterson Zah says despite the ongoing fight to protect minority voting rights in the state, he’s hopeful knowing that the current generation of young people want to make their voices heard.

“They’re not going to be deterred by some of those blocks that continue to be set up in front of them,” said Zah, who lives in Window Rock with his family. “They are going to do everything they can do to make sure that their rights are protected.”

Contact Grace Oldham on Twitter at @grace_c_oldham.