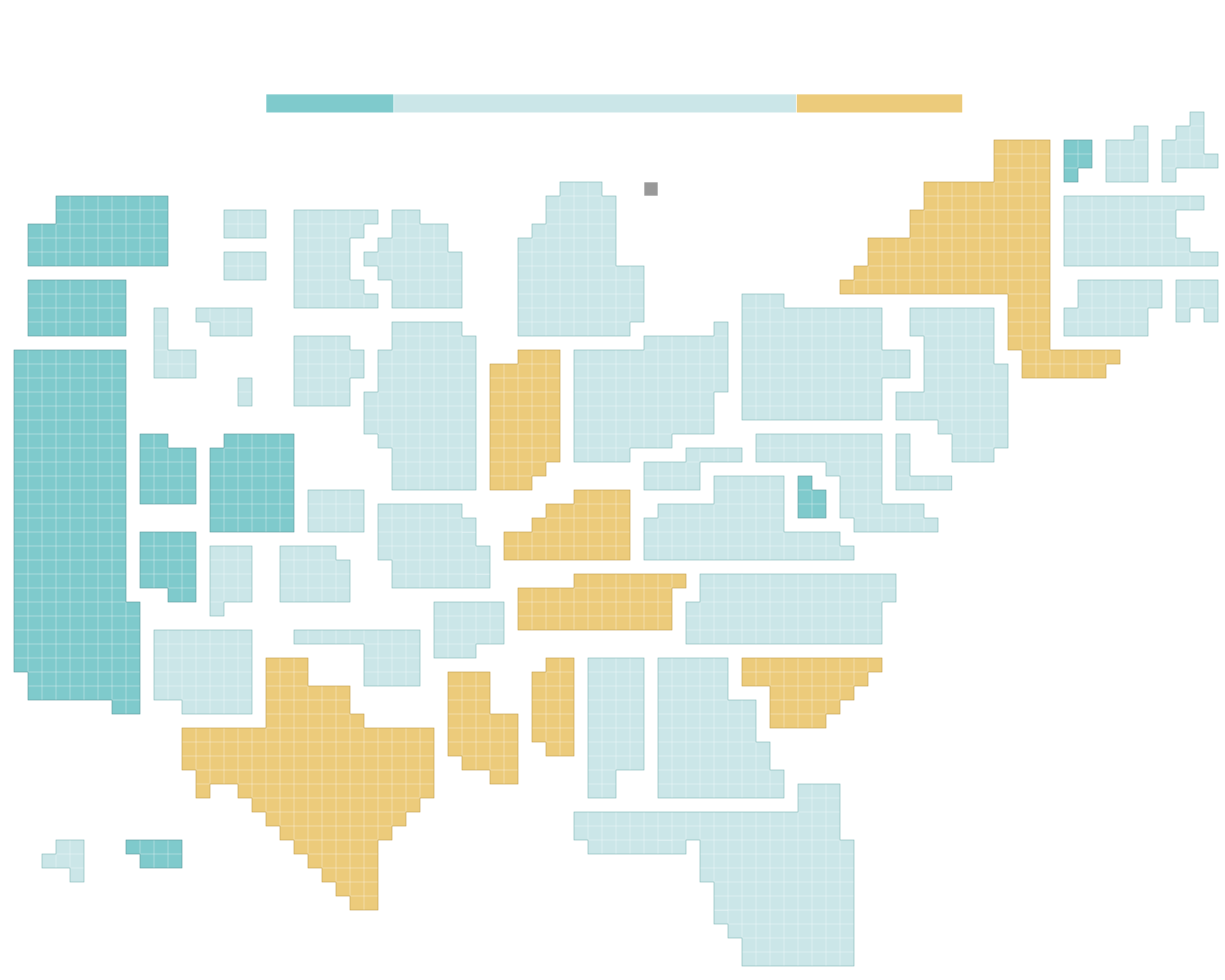

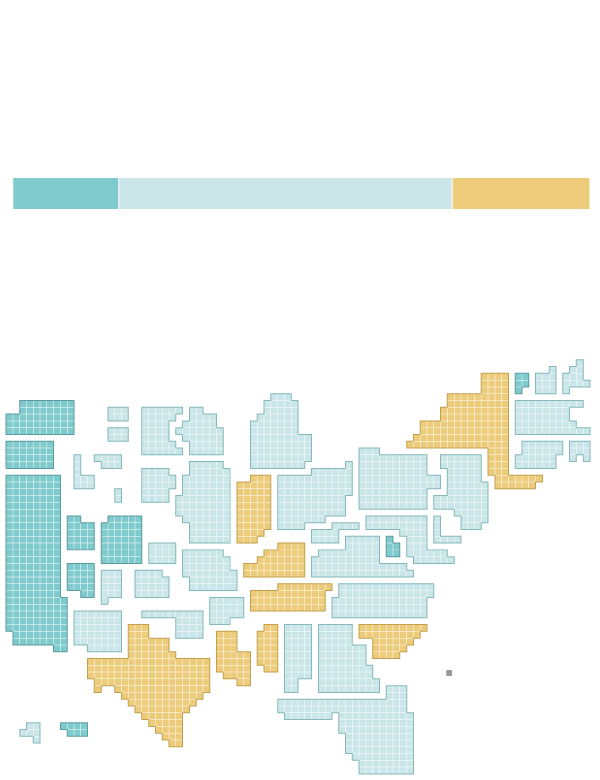

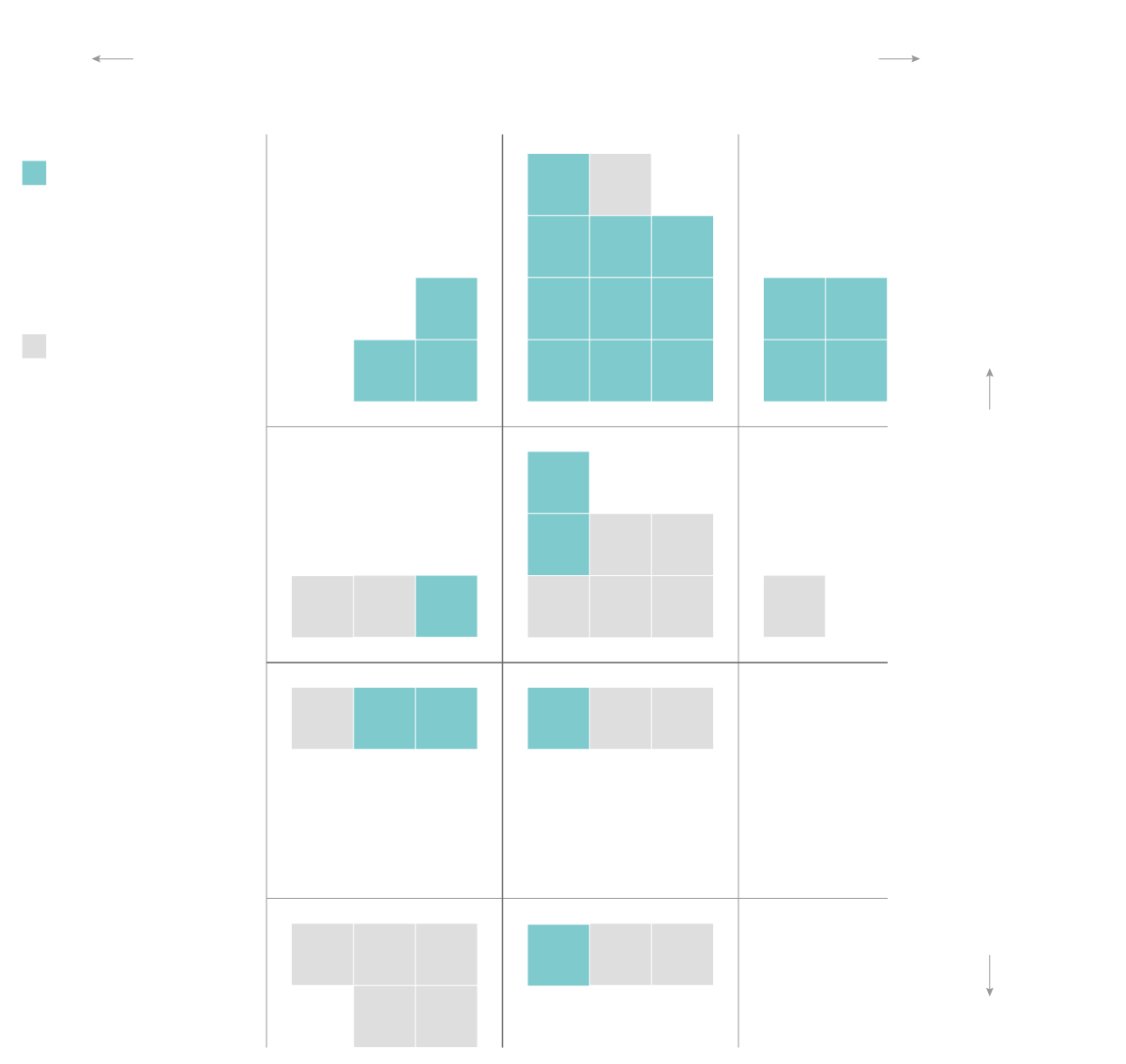

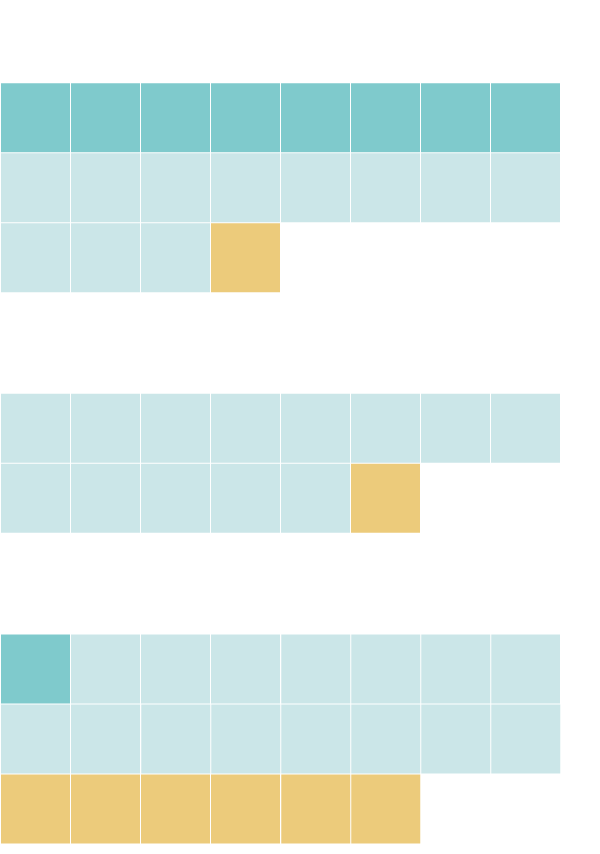

Ballots mailed

directly to all voters

Absentee voting

allowed for all

Excuse required

for absentee voting

38 million voters

in eight states + D.C.

120 million voters

in 34 states

50 million voters

in eight states

Each square

is 100,000

registered voters.

Calif.

Alaska

Hawaii

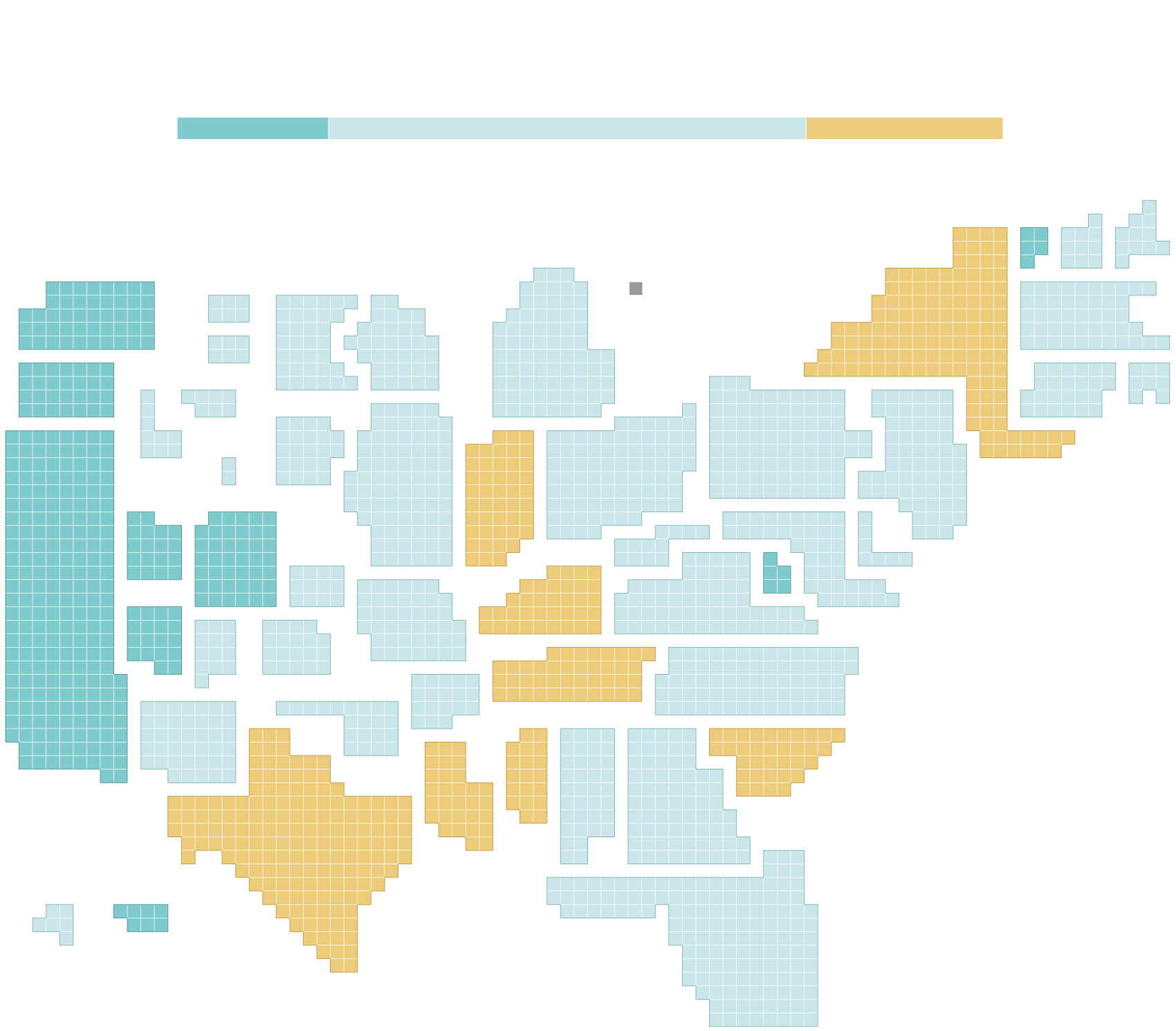

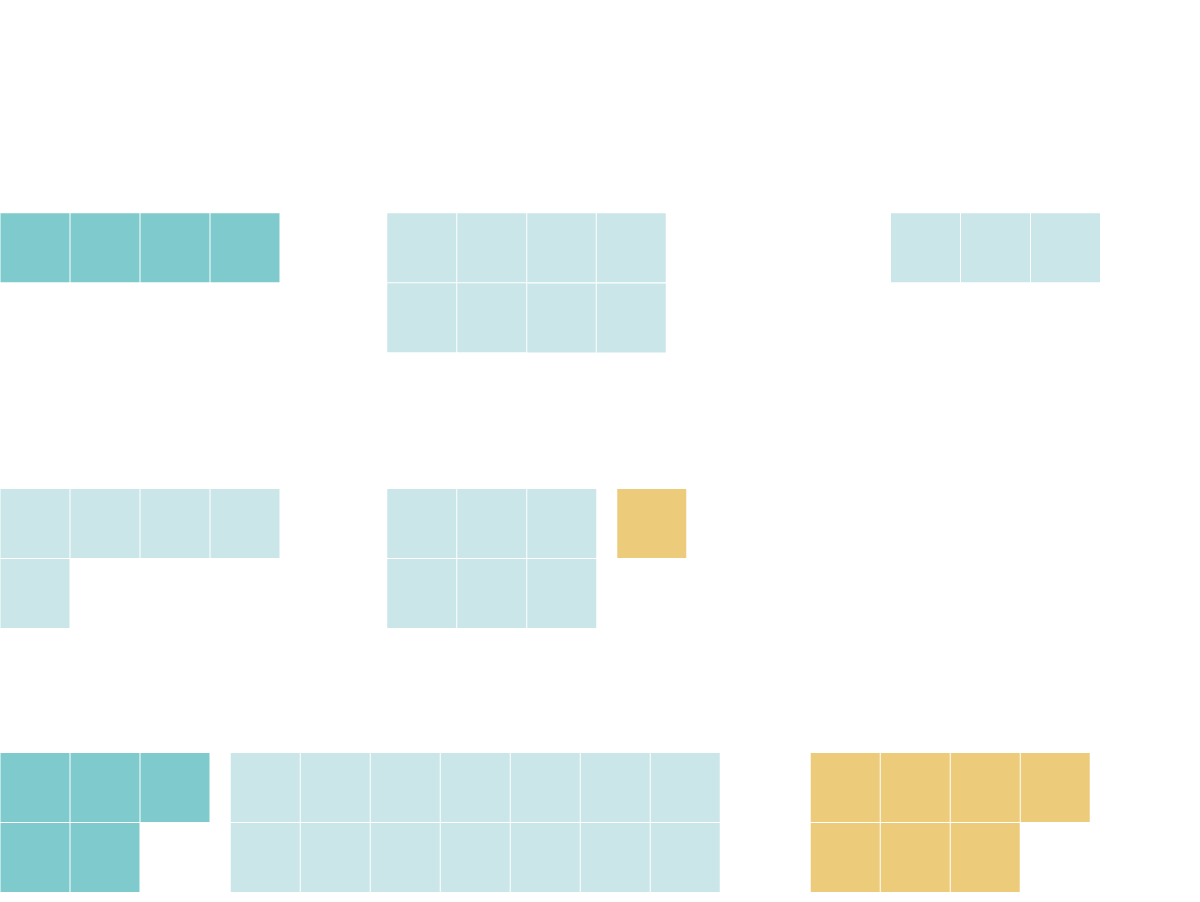

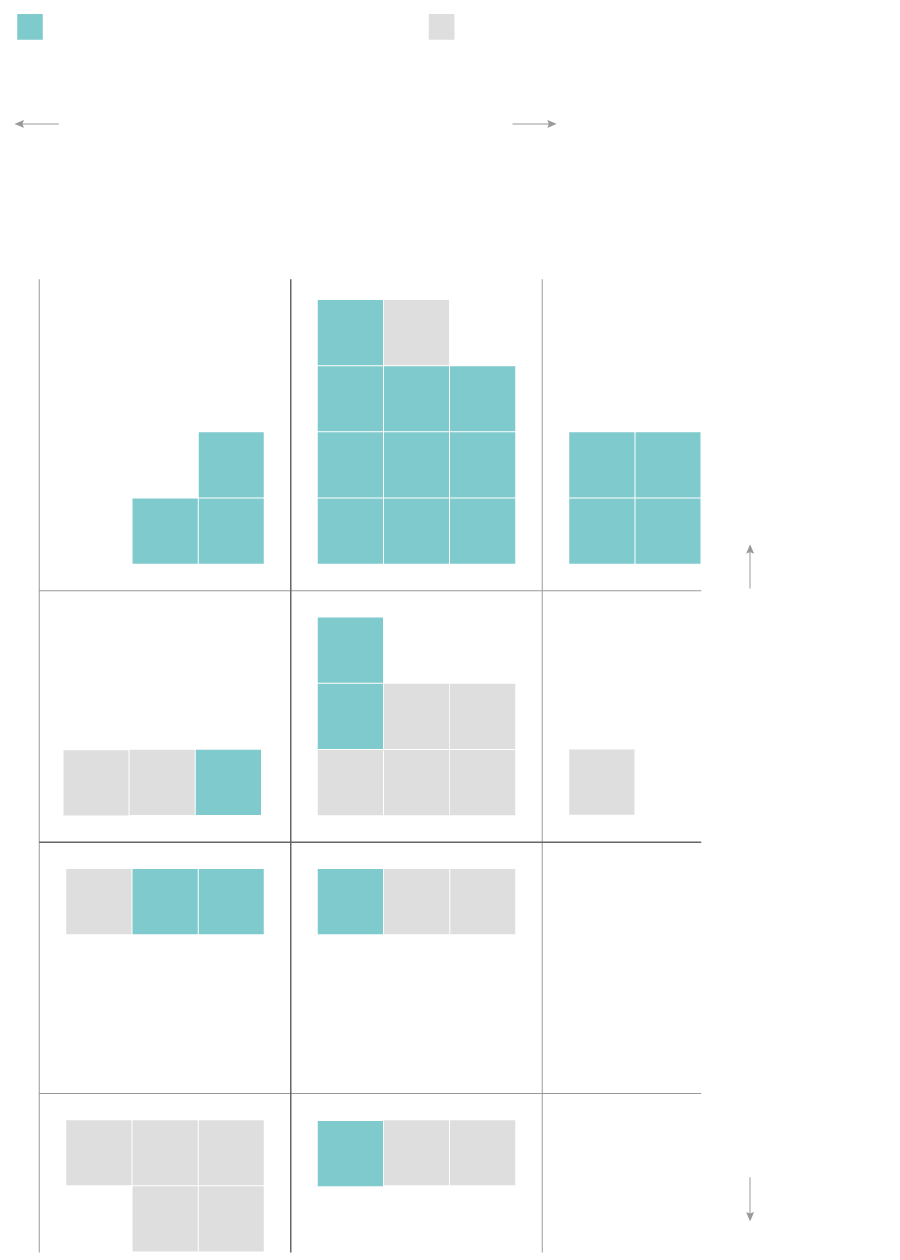

Ballots mailed

directly to all voters

Absentee voting

allowed for all

Excuse required

for absentee voting

38 million voters

in eight states + D.C.

120 million voters

in 34 states

50 million voters

in eight states

Each square is 100,000

registered voters.

Calif.

Alaska

Hawaii

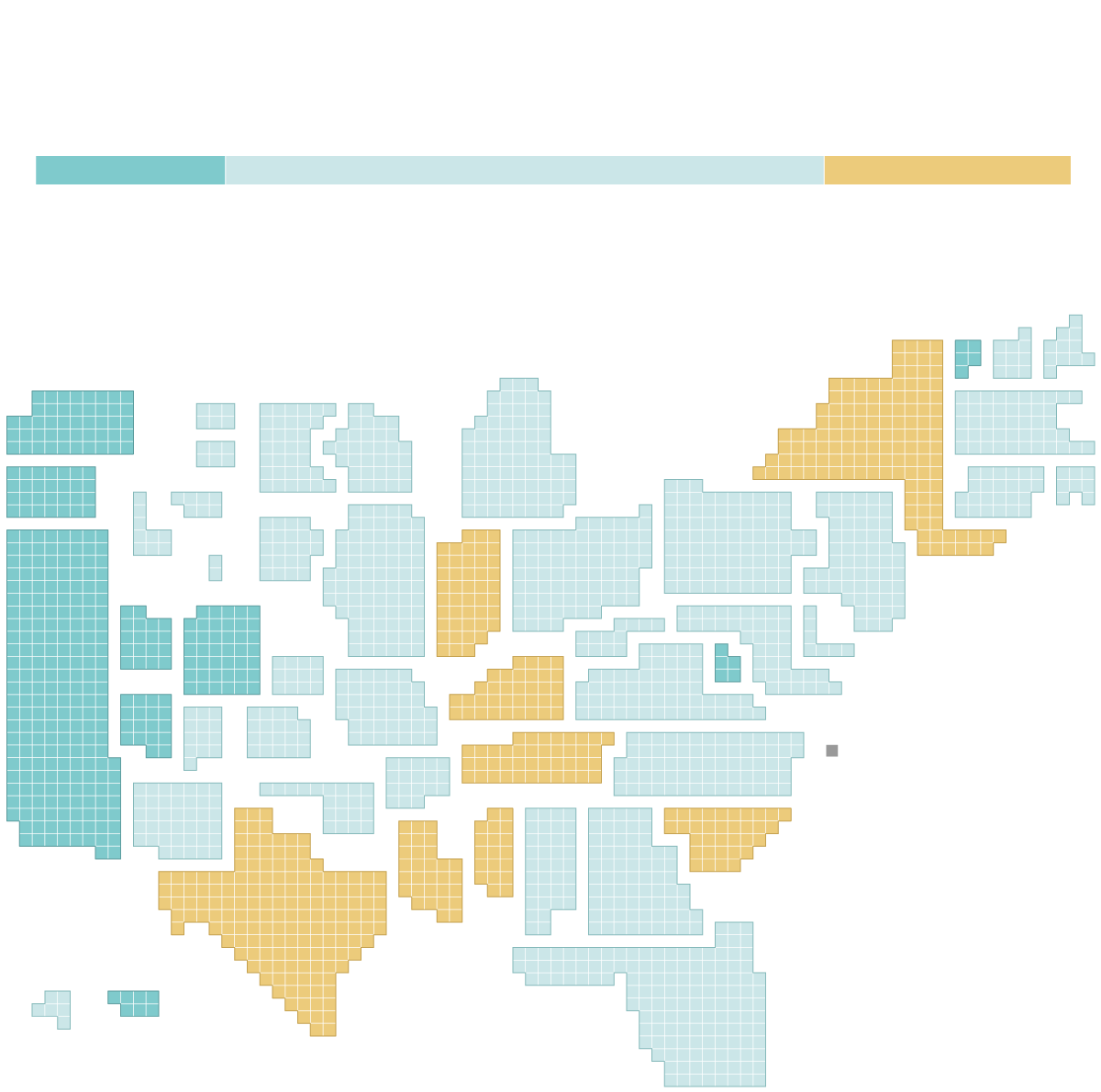

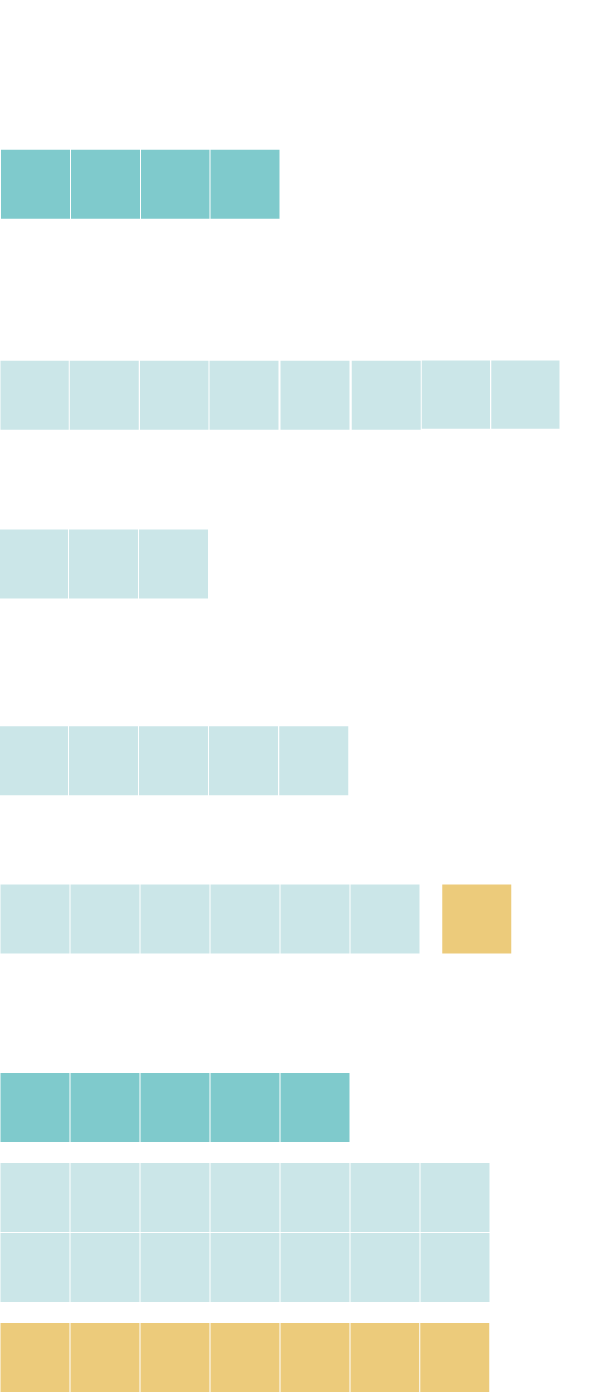

Ballots mailed

directly to all voters

Absentee voting

allowed for all

Excuse required

for absentee voting

38 million voters

in eight states + D.C.

120 million voters

in 34 states

50 million voters

in eight states

Calif.

Each square

is 100,000

registered voters.

Alaska

Hawaii

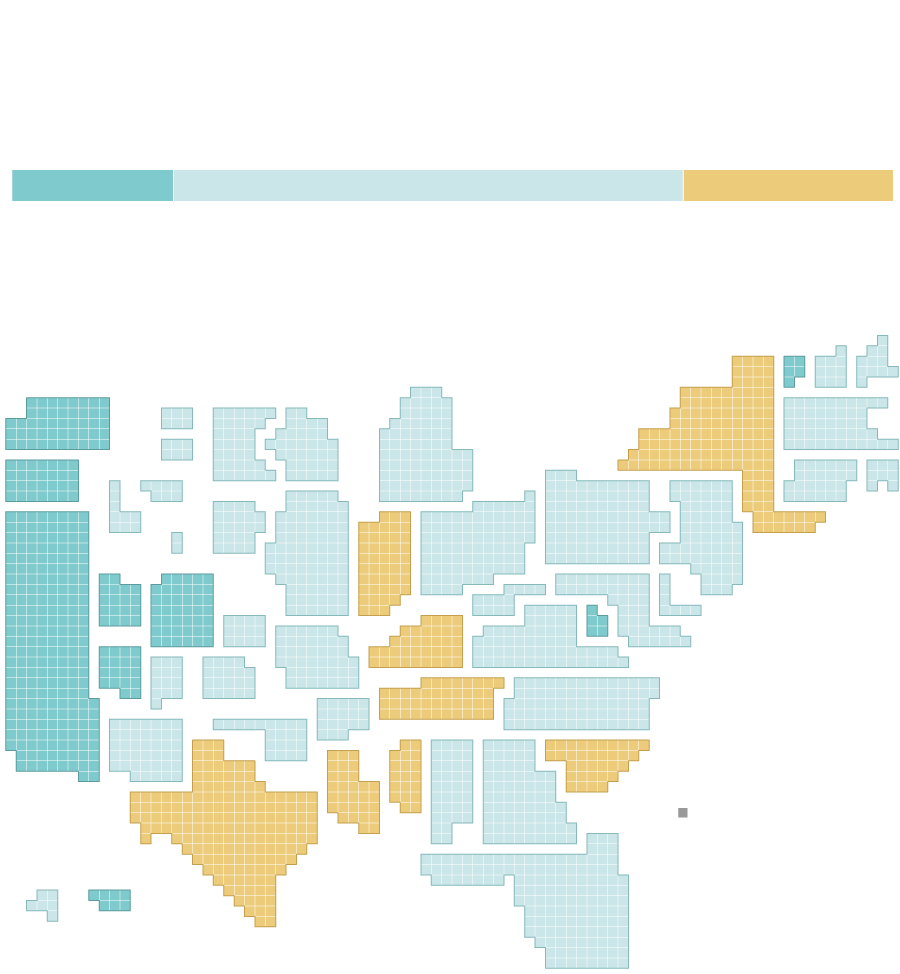

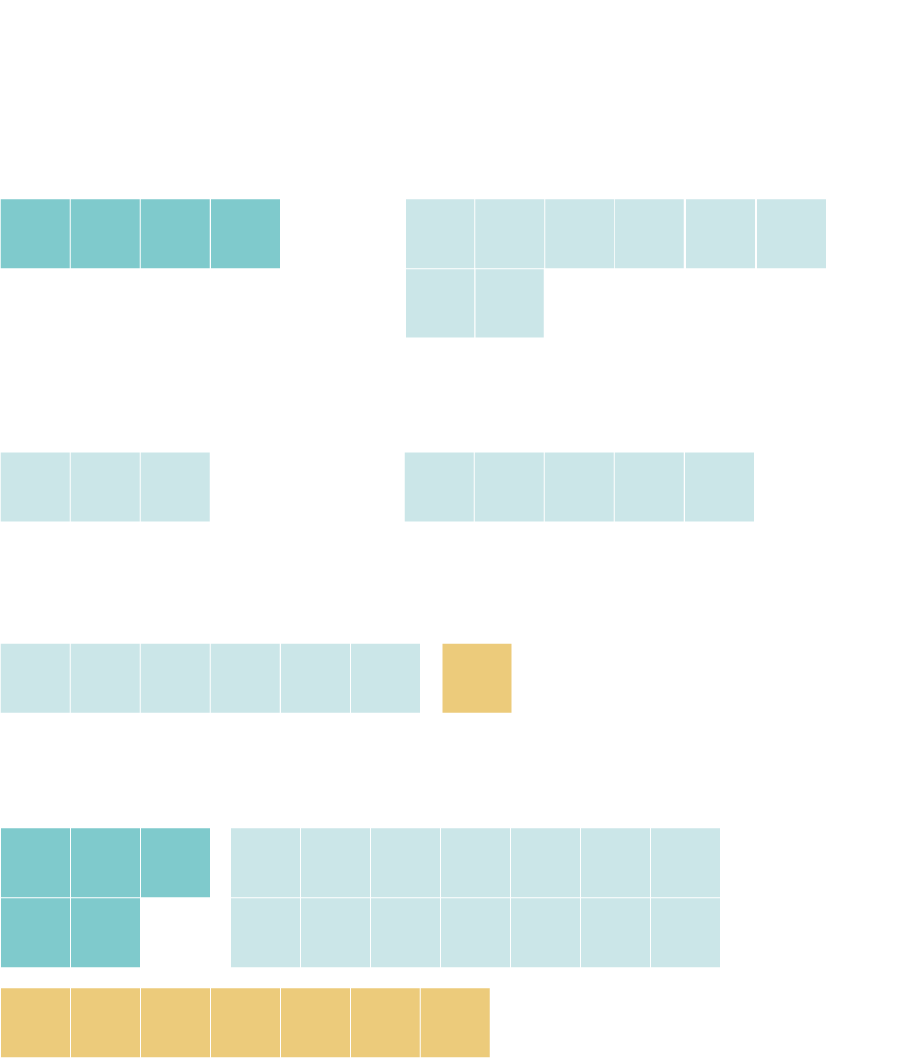

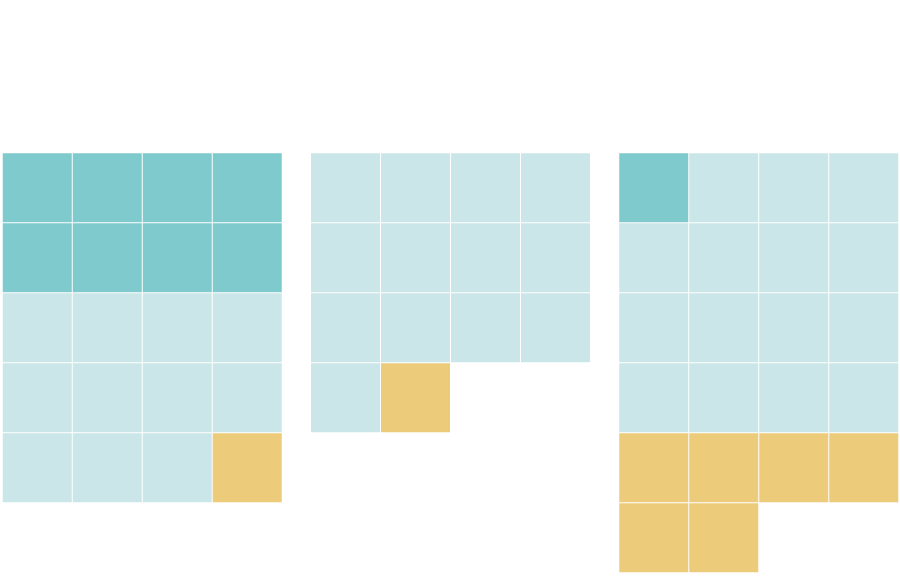

Ballots mailed

directly to all voters

Absentee voting

allowed for all

Excuse required

for absentee voting

38 million voters

in eight states + D.C.

120 million voters

in 34 states

50 million voters

in eight states

Each square

is 100,000

registered voters.

Ballots mailed

directly to

all voters

Absentee

voting allowed

for all

Excuse required

for absentee

voting

38 million

voters in eight

states + D.C.

120 million

voters in

34 states

50 million

voters in

eight states

Each square

is 100,000

registered

voters.

Note: Montana authorized its counties to mail ballots to all voters but in counties that opt not to, voters will still need to apply for an absentee ballot.

At least three-quarters of all American voters will be eligible to receive a ballot in the mail for the 2020 election — the most in U.S. history, according to a New York Times analysis. If recent election trends hold and turnout increases, as experts predict, roughly 80 million mail ballots will flood election offices this fall, more than double the number that were returned in 2016.

The rapid and seismic shift in how Americans will vote is because of the coronavirus pandemic. Concerns about the potential for virus transmission at polling places have forced many states to make adjustments on the fly that — despite President Trump’s protests — will make mail voting in America more accessible this fall than ever before.

“I have a hard time looking back at history and finding an election where there was this significant of a change to how elections are administered in this short a time period,” said Alex Padilla, the California secretary of state who chairs the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State.

Most of the changes are temporary and have been made administratively by state and local officials who have the power to make adjustments during emergencies like the pandemic.

Several of the states that made changes for the primaries are keeping them in place for the general election, while others are making separate adjustments for the fall. A handful of states have not made any modifications and appear unlikely to do so.

Over all, 24 states and Washington, D.C., have in some way expanded voter access to mail ballots for the 2020 general election, with the broad goal of making it easier for people to vote amid a global health crisis. And in some states that maintained relatively strict rules, individual counties have undertaken similar efforts.

Changes to voting in fall 2020

Ballots mailed

Absentee allowed for all

Excuse required

States that made changes

Sending ballots

to all voters

Sending absentee ballot

applications to all voters

Allowing no-excuse

absentee voting

Allowing voters to cite

Covid to vote absentee

Other changes to

ease absentee voting

States that made no changes

States that made changes

Sending ballots to all voters

Sending absentee ballot applications

to all voters

Allowing for no-excuse absentee voting

Allowing voters to cite Covid to vote

absentee

Other changes to ease absentee voting

No changes made

States that made changes

Sending ballots

to all voters

Sending absentee ballot

applications to all voters

Allowing for no-excuse

absentee voting

Allowing voters to cite Covid

to vote absentee

Other changes to ease absentee voting

No changes made

Note: Connecticut and Delaware have authorized absentee voting for all voters and will also mail absentee ballot applications.

Several new pieces of state legislation are also still pending, and experts say more changes could be forthcoming through executive action, litigation or other mechanisms in a few states, including New York.

But they also note that many Americans who choose to vote by mail this cycle because of the virus will simply be leveraging options that have long been available to them under existing laws.

More mail votes, higher turnout

During the presidential primaries, many states that made it easier for people to vote by mail saw higher turnout than states that made fewer changes.

Of the states that have held presidential primaries and caucuses this year, 31 saw an increase in turnout compared with 2016. Of those, 18 had sent either ballots or ballot applications to all voters ahead of the primaries.

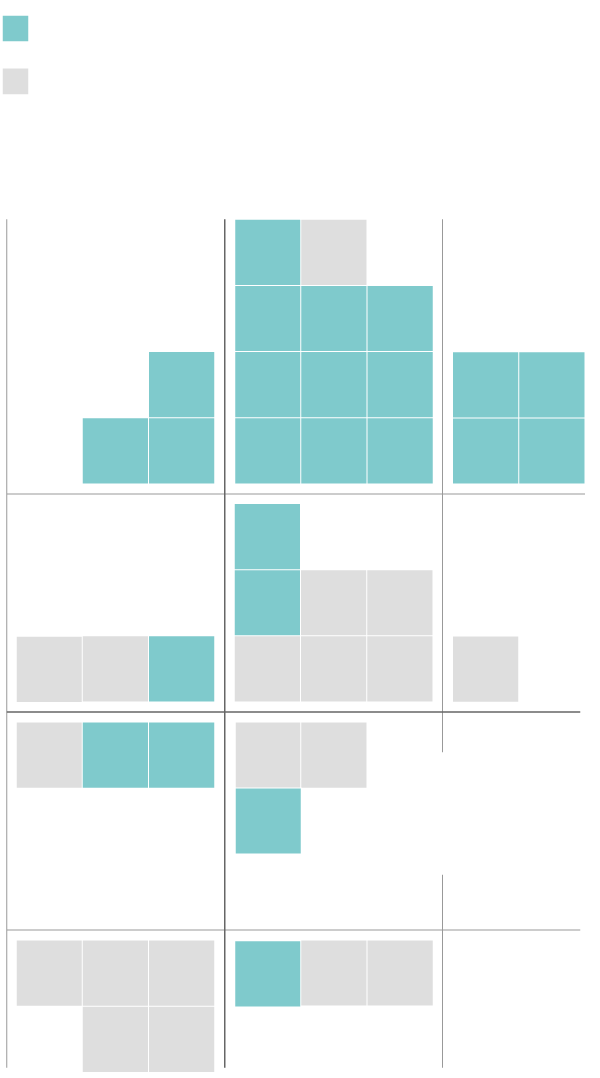

Turnout in presidential primaries and caucuses

Change in primary

turnout, 2016-2020

Lower turnout

Higher turnout

States that

sent ballots

or ballot

applications

States that

did not

More voted

by mail

Percentage

that voted

absentee in

2020 primary

Fewer voted

by mail

States that did not

States that sent ballots

or ballot applications

Lower

turnout

Higher

turnout

Change in primary

turnout, 2016-2020

More voted

by mail

Percentage

that voted

absentee in

2020 primary

Fewer voted

by mail

States that sent ballots or ballot applications

States that did not

Change in primary turnout, 2016-2020

Percentage that

voted absentee

in 2020 primary

Note: Seven states that have had primaries or caucuses are not shown in the chart because vote-by-mail data is not available. Of those, Minnesota and Wyoming had overall increases in turnout. Arkansas, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire and Tennessee had decreases in turnout.

Six states continued to require voters to have a reason other than the virus in order to vote absentee in the primaries. In those states, voter turnout stayed roughly the same as 2016.

Michael P. McDonald, a University of Florida professor who studies American elections, said that recent election trends, including many of this year’s primaries, have indicated that turnout will be up in the fall compared with 2016, and that the widespread use of mail voting will shatter previous records.

“It’s sort of trite to say that you’re going to have the highest turnout rate of your lifetime or this is the most important election of your lifetime, but it really feels like that,” he said. “I’m still expecting this to have very high turnout in November. The outstanding question that we have is just: Will the election system be able to bear that?”

Indeed, the primaries also exposed the myriad problems that elections officials and voters could face this fall.

In Wisconsin, 11th-hour court rulings, long lines at the polls, a backlog of absentee ballot requests and complaints about missing or nullified mail ballots stretched the system to the brink of collapse. In Georgia’s most populous county, voters encountered an election meltdown rife with their own interminable lines and malfunctioning technology. And in New York, it took several weeks for overwhelmed officials to count thousands of mail ballots and deliver results.

All the while, Mr. Trump has fiercely criticized mail voting — while allowing that military members and older Americans should be allowed to vote absentee — saying that sending ballots to voters directly would compromise the election’s integrity. More broadly, some Republicans have continued to insist without evidence that voting by mail favors Democrats.

Mail voting has expanded unevenly along somewhat partisan lines: Several of the states identified by The Cook Political Report as solid or likely Democratic in the 2020 general election have implemented some of the most expansive mail voting programs; many of the states identified as solid or likely Republican have continued to restrict access to mail voting.

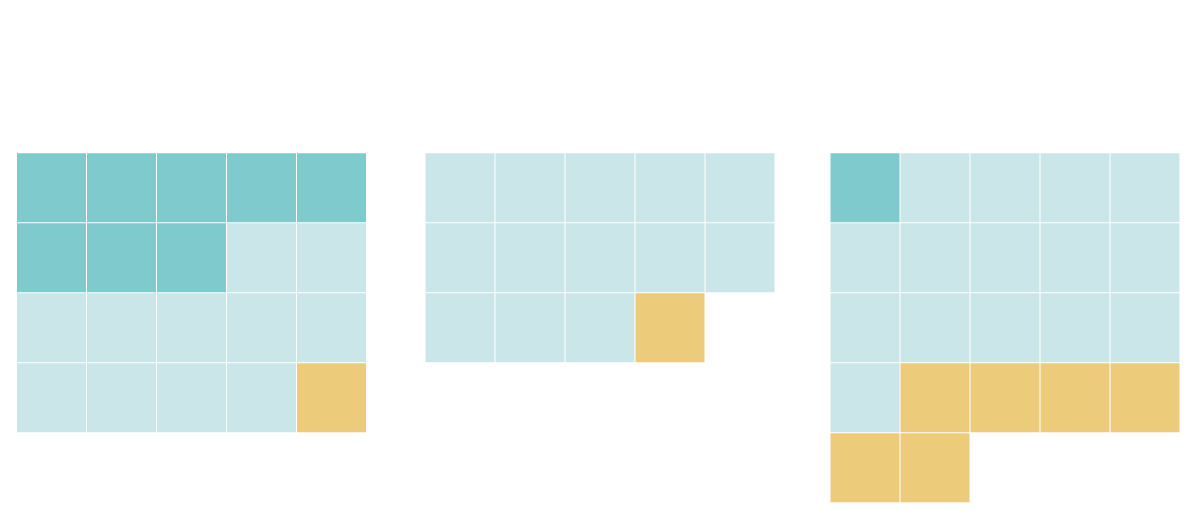

Cook Political Report ratings for 2020 Electoral College

Ballots mailed

Absentee allowed for all

Excuse required

Solid + Likely

Democratic

Toss-ups

and leans

Solid + Likely

Republican

Solid + Likely Democratic

Toss-ups and leans

Solid + Likely Republican

Solid + Likely

Democratic

Toss-ups

and leans

Solid + Likely

Republican

Note: Maine and Nebraska select electors using the District method, in which each congressional district in the state selects its own elector, and the remaining two electoral college votes are determined by the popular vote winner.

Studies have repeatedly shown that voting fraud of any kind is extremely rare in the United States. And states and counties that have transitioned to all-mail voting have seen little evidence of partisan advantage.

Potential problems in November

Researchers said that thinly stretched election offices might quickly become overwhelmed by the volume of mail ballots. To help lessen their load, elections officials in several key swing states have already asked that lawmakers give them more leeway to prepare absentee ballots for counting as they arrive rather than after the polls close.

Their problems could be compounded by a lack of funding for the Postal Service. If there are slowdowns in either election offices or post offices, experts said, ballots may not get sent out in a timely manner or returned by postmark deadlines.

Richard L. Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine, said he remained “very worried” that scores of voters would be disenfranchised through no fault of their own. Because many voters will be unfamiliar with the mail voting process, he and other experts said, they were concerned that voters could make unintentional technical errors when marking, signing, sealing or sending a ballot, leading to their ballots eventually being rejected.

And those voting in person may have to confront poll worker shortages that onlookers say are likely to be exacerbated by the pandemic.

“It’s going to be bumpy,” said Amber McReynolds, the chief executive of the National Vote at Home Institute and Coalition. “Will it be a disaster in a particular state? That’s hard to tell at this moment.”

Well-prepared states that are accustomed to counting a high number of mail ballots — and where the presidential race is not close — could get called on election night. But experts say that in other states, the counting could delay race calls for at least a day or two. And in states where the presidential contest is tight and laws are inflexible, a clear picture of who has won could take weeks to develop.

Despite the challenges, Phil Keisling, who was Oregon’s secretary of state when it began mailing ballots to voters more than two decades ago, was among more than a half-dozen experts who expressed faith that election administrators would get their jobs done.

“Tens of millions of people are in election terra incognita, and so there’s anxiety, and it’s understandable,” Mr. Keisling said. “But I am guardedly optimistic that we will run an election that will meet very high standards of professionalism, and that the vast majority of Americans, even if they don’t like the results, are going to believe that the results are fair.”