Advertisement

Even the goal of defeating President Trump isn’t enough for some voters to commit to backing the eventual Democratic nominee, expressing a clear aversion to a candidate who is too liberal or centrist for their tastes.

FORT DODGE, Iowa — Democrats have always represented a cacophonous array of individuals and interests, but the so-called big tent is now stretching over a constituency so unwieldy that it’s easy to understand why voters remain torn this close to Iowa, where no clear front-runner has emerged.

The party’s voters are splintered across generational, racial and ideological lines, prompting some liberals to express reluctance about rallying behind a moderate presidential nominee, and those closer to the political middle to voice unease with a progressive standard-bearer.

The lack of a united front has many party leaders anxious — and for good reason. In over 50 interviews across three early-voting states — Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina — a number of Democratic primary voters expressed grave reservations about the current field of candidates, and in some cases a clear reluctance to vote for a nominee who was too liberal or too centrist for their tastes.

As she walked out of a campaign event for former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. in Fort Dodge this week, Barbara Birkett said she was leaning toward caucusing for Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, and dismissed the notion of even considering the two progressives in the race, Senators Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

“No, I’m more of a Republican and that’s just a little bit too far to the left for me,” Ms. Birkett, a retiree. She said that she’d like to support a Democrat this November because of her disdain for Mr. Trump but that Mr. Sanders would “be a hard one.”

Elsewhere on the increasingly broad Democratic spectrum, Pete Doyle, who attended a Sanders rally in Manchester, N.H., last weekend, had a ready answer when asked about voting for Mr. Biden: “Never in a million years.” He said that if Mr. Biden won the nomination, he would either vote for a third-party nominee or sit out the general election.

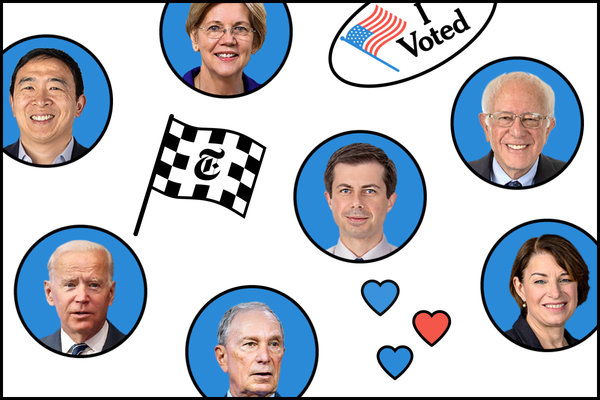

The Iowa caucuses are around the corner. As you get ready for primary season, take a look at our cheat sheet on the race.

The uncertainty about party unity has been exacerbated in recent days by clashes among the Democratic candidates, as well as one involving a prominent party leader.

Mr. Sanders and Ms. Warren have accused one another of lying about a private conversation in 2018 over whether a woman could become president; Mr. Sanders and Mr. Biden have attacked each other over Social Security and corruption; and Hillary Clinton, the 2016 Democratic nominee, has come off the sidelines to stoke her rivalry with Mr. Sanders, declaring that “nobody likes him.”

The lack of consensus among Democratic voters, 10 days before the presidential nominating primary begins with Iowa caucuses, has led some party leaders to make unusually fervent and early pleas for unity. On Monday alone, a pair of influential Democratic congressmen issued strikingly similar warnings to very different audiences in very different states.

“We get down to November, there’s only going to be one nominee,” Representative James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, the third-ranking House Democrat, said at a ceremony for Martin Luther King’s Birthday at the State House in Columbia. “Nobody can afford to get so angry because your first choice did not win. If you stay home in November, you are going to get Trump back.”

“No matter who our nominee is, we can’t make the mistake that we made in ’16,” Representative Dave Loebsack of Iowa said that night in Cedar Rapids as he introduced his preferred 2020 candidate, former Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., at a town hall meeting. “We all got to get behind that person so we can get Donald Trump out of office,” Mr. Loebsack added.

In interviews, Democratic leaders say they believe the party’s fights over such politically fraught issues as treasured entitlement programs, personal integrity, and gender and electability could hand Mr. Trump and foreign actors ammunition with which to depress turnout for their standard-bearer.

“I am concerned about facing another disinformation campaign from the other side,” said Representative Brendan Boyle of Pennsylvania, a Biden supporter who was uneasy enough that he recently sought out high-profile congressional backers of some of the other contenders to discuss an eventual détente. “For those of us who are elected officials, we need to exercise real leadership to make sure all of the camps are immediately united after all this is over.”

Most Democrats believe that the deep revulsion their party’s voters and activists share for Mr. Trump will ultimately help heal primary season wounds and rally support behind whoever emerges as the nominee. “If it means getting rid of Donald Trump, they would swallow Attila the Hun,” State Representative Todd Rutherford, the Democratic leader of the South Carolina House, said of his party’s rank-and-file.

And some leading Democrats were less worried about recovering from the cut-and-thrust of the primary fights than figuring out how to address the deep fissures within their coalition that this race has exposed.

“The Democrats cover everybody from Bernie to Bloomberg and that does present a real problem in terms of making a decision,” said former Gov. Jerry Brown of California, himself a former presidential hopeful, referring to former Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg of New York. “It’s not blendable at this point. And if the division continues you’re not going to get a first-ballot candidate.”

The political and cultural distance between the two leading Democratic candidates, Mr. Biden and Mr. Sanders, is easy enough to grasp from their events.

A rally for Mr. Sanders in Exeter, N.H., last weekend featured the actor John Cusack, who introduced his candidate by invoking left-wing writers like Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn and denouncing neoliberalism and imperialism.

The event had few of the trappings of Mr. Biden’s events, like the Pledge of Allegiance and a call for blessings upon the American military and the restoration of consensus and comity in Washington. The former vice president does not ask his audiences to raise their hands if they know anyone arrested for marijuana possession, as Mr. Sanders usually does.

Vivid as the surface differences are between Mr. Sanders and Mr. Biden, what’s even more revealing are the views that emerge in polling and conversations with their supporters.

A new CNN survey showed that about as many Democrats under 50 would be upset or dissatisfied with Mr. Biden as the nominee as they would be enthusiastic. And among those older than 65, views were even starker about Mr. Sanders: just 23 percent said they’d be enthusiastic about him while 33 percent said they’d be upset or dissatisfied.

Mr. Sanders has tried to bolster his standing with older voters, and lessen their ardor for Mr. Biden, by trumpeting his support for Social Security and highlighting the former vice president’s past willingness to consider cuts to the program — a contrast Sanders supporters believe is vital given Mr. Trump’s suggestion this week that he’d pursue entitlement trims.

Interviews with Sanders supporters at his events in New Hampshire and at the King Day gathering in South Carolina revealed a group of progressive activists who were as dedicated to him as they were in 2016 — and who were uneasy about his rivals, especially Mr. Biden. That was borne out in a new poll of New Hampshire primary voters this week from Suffolk University, which indicated that nearly a quarter of the Vermont senator’s supporters would not commit to backing the party’s nominee if it was not Mr. Sanders.

That number could drop by November if Mr. Sanders does not win the nomination: research shows that most of Mr. Sanders’s supporters eventually rallied to Mrs. Clinton against Mr. Trump. Yet it would not necessarily happen easily, especially if Mr. Sanders’s supporters believe he’s been treated unfairly by the party.

Many Sanders supporters who said they would grudgingly support one of his rivals against Mr. Trump quickly added that that’s all they’d do, ruling out doing the volunteer work that is the lifeblood of all campaigns.

“I just couldn’t morally,” Laura Satkowski said, explaining why she would not canvass or make phone calls on behalf of Mr. Biden. “I don’t like his policies.”

Some pro-Sanders households are mixed.

Michelle McKay and her partner, Bill Davis, came to the South Carolina State House from their home in Raleigh, N.C., she wearing a vest festooned with Sanders buttons, to show their support for their candidate.

“Hell no,” Ms. McKay said about the prospect of backing Mr. Biden. Reminded that North Carolina could be a pivotal state in the general election, she said: “I don’t care. My vote is not going to an establishment Democrat.”

Mr. Davis, though, said that while he didn’t want to vote for anybody besides Mr. Sanders, he’d cast a ballot for any Democrat against Mr. Trump. “I think the party will come together,” he said, as Ms. McKay looked on unconvinced.

For many Democratic leaders, the hope for party unity rests on shared loathing of Mr. Trump. His divisive record and conduct in office helped propel Democrats to a new House majority in 2018 and a number of governorships in the last three years.

Yet while his astonishing election and often demagogic politics have accelerated the rise of the left, energizing a new generation of progressives and socialists, Mr. Trump’s presidency has also enlarged the moderate wing of the party, creating a slice of de facto Democrats among the Republicans and right-leaning independents who cannot abide him.

Phil Richardson, a farmer who came to the Biden event in Fort Dodge with his wife, Christy, said he’d be happy to vote for Mr. Sanders.

But Mr. Richardson said his worry is that others in his community would find it harder to support somebody so liberal.

“I’ve had some of my farmer friends tell me they could probably live with Biden but he couldn’t go for Bernie,” he said.

Over in Dubuque, Iowa, Ron Davis said flatly that he’d support Mr. Trump if Mr. Sanders was the nominee.

An Ames, Iowa, native who now lives in suburban Detroit, Mr. Davis and his wife, Barbara Rom, are retirees traversing Iowa as political tourists this week — “candidate groupies,” he called them — and trying to decide who to support in Michigan’s primary in March.

On Wednesday they came to the University of Dubuque to see Mr. Buttigieg, who impressed Mr. Davis. Mr. Sanders, however, would be “too radical a change,” he said. Ms. Rom said she’d back Mr. Sanders if it meant defeating Mr. Trump.

If it all seems messy, and the party hopelessly fragmented, that’s for good reason, said Kathleen Sebelius, the former Kansas governor and health and human services secretary who grew up in Democratic politics as the daughter of a former Ohio governor.

“This primary is a reflection of the politics of the country at large,” Ms. Sebelius said. “There are clearly differences among people who still feel incremental change is the best way of getting things done, and folks who say we need more to pursue more radical change.”

She said she’d be more worried if Democrats didn’t have Mr. Trump as “a rallying cry,” but conceded there was no candidate on the horizon who could fully unify the party’s factions.

“There is no savior who’s going to rescue us from the current state of affairs,” she said. “We’re all going to need to save each other.”