Advertisement

President Trump continues to press for a quick return to life as usual, but Republicans who fear a rampaging disease and angry voters are increasingly going their own way.

President Trump’s failure to contain the coronavirus outbreak and his refusal to promote clear public-health guidelines have left many senior Republicans despairing that he will ever play a constructive role in addressing the crisis, with some concluding they must work around Mr. Trump and ignore or even contradict his pronouncements.

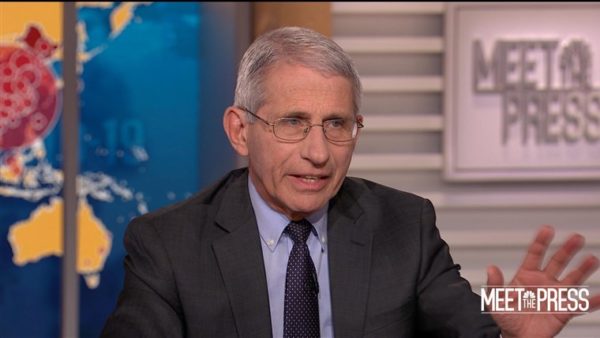

In recent days, some of the most prominent figures in the G.O.P. outside the White House have broken with Mr. Trump over issues like the value of wearing a mask in public and heeding the advice of health experts like Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, whom the president and other hard-right figures within the administration have subjected to caustic personal criticism.

They appear to be spurred by several overlapping forces, including deteriorating conditions in their own states, Mr. Trump’s seeming indifference to the problem and the approach of a presidential election in which Mr. Trump is badly lagging his Democratic challenger, Joseph R. Biden Jr., in the polls.

Once-reticent Republican governors are now issuing orders on mask-wearing and business restrictions that run counter to Mr. Trump’s demands. Some of those governors have been holding late-night phone calls among themselves to trade ideas and grievances; they have sought out partners in the administration other than the president, including Vice President Mike Pence, who, despite echoing Mr. Trump in public, is seen by governors as far more attentive to the continuing disaster.

“The president got bored with it,” David Carney, an adviser to the Texas governor, Greg Abbott, said of the pandemic. He noted that Mr. Abbott, a Republican, directs his requests to Mr. Pence, with whom he speaks two to three times a week.

A handful of Republican lawmakers in the Senate have privately pressed the administration to bring back health briefings led by figures like Dr. Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx, who regularly updated the public during the spring until Mr. Trump upstaged them with his own briefing-room monologues. And in his home state of Kentucky last week, Senator Mitch McConnell, the majority leader, broke with Mr. Trump on nearly every major issue related to the virus.

Mr. McConnell stressed the importance of mask-wearing, expressed “total” confidence in Dr. Fauci and urged Americans to follow guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that Mr. Trump has ignored or dismissed.

“The straight talk here that everyone needs to understand is: This is not going away until we get a vaccine,” Mr. McConnell said on Wednesday, contradicting Mr. Trump’s rosy predictions.

The result is a quiet but widening breach between Mr. Trump and leading figures in his party, as the virus burns through major political battlegrounds in the South and the West, like in the states of Arizona, Texas and Georgia.

Amid mounting alarm in a huge portion of the country, Mr. Trump has at times appeared to inhabit a different universe, incorrectly predicting the outbreak would quickly dissipate and falsely claiming the spread of the virus was simply a function of increased testing. With his impatient demands and decrees, Mr. Trump has disrupted efforts to mitigate the crisis while effectively sidelining himself from participating in those efforts.

The emerging rifts in Mr. Trump’s party have been slow to develop, but they have rapidly deepened since a new surge in coronavirus cases began to sweep the country last month.

In the final days of June, the governor of Utah, Gary Herbert, a Republican, joined other governors on a conference call with Mr. Pence and urged the administration to do more to combat a sense of “complacency” about the virus. Mr. Herbert said it would help states like his own if Mr. Trump and Mr. Pence were to encourage mask-wearing on a national scale, according to a recording of the call.

“As a responsible citizen, if you care about your neighbor, if you love your neighbor, let us show the respect necessary by wearing a mask,” Mr. Herbert said, offering language to Mr. Pence and adding, “That’s where I think you and the president can help us out.”

Mr. Pence told Mr. Herbert the suggestion was “duly noted” and said that mask-wearing would be a “very consistent message” from the administration.

But no such appeal was ever forthcoming from Mr. Trump, who asserted days later that the virus would “just disappear.”

Mr. Trump has offered only hedged recommendations on wearing masks and has rarely worn one himself in public; in a Fox interview that was broadcast on Sunday the president said he would not issue a national mask order, because Americans deserve “a certain freedom” on the matter.

Some of the states where outbreaks have worsened most in recent weeks are led by Republicans who spent months avoiding stringent lockdowns, in some cases because state leaders were uneasy about creating space between themselves and a president of their own party who rejected such steps. That dynamic has been particularly pronounced in Southern states like Mississippi, Alabama and Florida, where governors have either continued to resist tough public-health restrictions or have only recently and partially embraced them.

A few Republicans have grown more open with their misgivings about Mr. Trump’s approach, including Gov. Asa Hutchinson of Arkansas, who said this month that he would require people to wear masks at any Trump rallies in his state. After issuing a broad mask mandate last week, Mr. Hutchinson said on the ABC program “This Week” on Sunday that an “example needs to be set by our national leadership” on mask-wearing.

Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, a Republican, in an interview on “Meet the Press” on NBC, did not answer directly when asked if he had confidence in Mr. Trump’s leadership in the crisis. Mr. DeWine said he had confidence “in this administration” and praised Mr. Pence for “doing an absolutely phenomenal job.”

Judd Deere, a White House spokesman, rejected criticisms of Mr. Trump’s approach.

“Any suggestion that the president is not working around the clock to protect the health and safety of all Americans, lead the whole-of-government response to this pandemic, including expediting vaccine development, and rebuild our economy is utterly false,” Mr. Deere said in a statement.

With only a few exceptions, Republicans have avoided direct confrontation with Mr. Trump. They’ve come to view public criticism as an exercise in political futility — one guaranteed to produce a sour response from Mr. Trump without any chance of changing his behavior.

But many Republican lawmakers have grown exasperated with the administration’s conflicting messages, the open warfare within Mr. Trump’s staff and the president’s demands that states reopen faster or risk punishment from the federal government.

Senator Ben Sasse, Republican of Nebraska, said he wanted the administration to offer more extensive public-health updates to the American people, and condemned the open animosity toward Dr. Fauci by some administration officials, including Peter Navarro, the trade adviser, who wrote an opinion column attacking Dr. Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert.

“I want more briefings but, more importantly, I want the whole White House to start acting like a team on a mission to tackle a real problem,” Mr. Sasse said. “Navarro’s Larry, Moe and Curly junior-high slap fight this week is yet another way to undermine public confidence that these guys grasp that tens of thousands of Americans have died and tens of millions are out of work.”

Senator Roy Blunt, Republican of Missouri, was more succinct: “The more they turn the briefings over to the professionals, the better.”

A group of Republican governors have for months held regular conference calls, usually at night and without staff present, according to two party strategists familiar with the conversations. Unlike the virus-focused calls that Mr. Pence leads, there are no Democratic or White House officials on the line, so the conversations have become a sort of safe space where the governors can ask their counterparts for advice, discuss best practices and, if the mood strikes them, vent about the administration and the president’s erratic leadership.

Mr. Trump himself seems less interested in the specific challenges the virus presents and is mostly just frustrated by the reality that it has not disappeared as he has predicted. The disconnect is only growing between him and other party leaders — not to mention voters. A poll published Friday by ABC News and The Washington Post found that a majority of the country strongly disapproved of Mr. Trump’s handling of the coronavirus crisis, and about two-thirds of Americans said they had little or no trust in Mr. Trump’s comments about the disease.

Mr. Trump’s political standing is now so dire that even Republicans who have spent years avoiding direct comment on his behavior are acknowledging his unpopularity in plain terms. Former House Speaker Paul Ryan, for instance, offered a bleak assessment of Mr. Trump’s electoral standing at a recent event hosted by Solamere, a company with close ties to Senator Mitt Romney, Republican of Utah, and his family.

According to a partial transcript of the comments, shared by a person close to him, the usually tight-lipped Mr. Ryan said Mr. Trump was losing key voting blocs across the Midwest and in Arizona, a Republican-leaning state that Mr. Ryan described as “presently trending against us.”

While Mr. Ryan did not criticize Mr. Trump’s handling of the outbreak, he said the president could not win re-election this year if he continued losing badly to Mr. Biden among suburban voters who were wary of both candidates but currently favor Mr. Biden.

“Biden is winning over Trump in this category of voters 70 to 30,” Mr. Ryan said, “and if that sticks, he cannot win states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.”

Some of Mr. Trump’s closest advisers are adamant that the best way forward is to downplay the dangers of the disease. Mark Meadows, the chief of staff, has been particularly forceful in his view that the White House should avoid drawing attention to the virus, according to people familiar with the discussions.

Mr. Meadows has for the most part opposed any briefings about the virus, while other Trump advisers, including Hope Hicks and Jared Kushner, have been open to holding briefings so long as they are not at the White House — where Mr. Trump could show up and commandeer them. Mr. Pence’s team would like to hold more briefings with the health experts, but some of Mr. Trump’s communications aides do not want the vice president to be part of them.

A large number of rank-and-file Republican lawmakers share Mr. Trump’s aversion to the disease-control practices.

Gov. Brian Kemp of Georgia, a Republican closely aligned with Mr. Trump, issued an order on Wednesday blocking local governments from mandating mask-wearing, then sued the mayor of Atlanta, Keisha Lance Bottoms, for imposing such a requirement. Mr. Kemp’s edict came hours after Mr. Trump visited his state, declining to wear a face mask at the Atlanta airport.

Yet some in the G.O.P. now see no alternative to parting ways with Mr. Trump, on policy if not politics.

Glenn Hamer, president of the Arizona Chamber of Commerce and Industry, a powerful business federation in the crucial state, said he saw Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican, walking a prudent line — breaking with Mr. Trump’s policy demands but not blasting the president for issuing them.

“Everyone knows that the president doesn’t react well to criticism, constructive or not,” he said.

Mr. Hamer, who was among a group of business leaders who sent a letter to the White House urging the creation of clearer national standards for facial coverings, said Mr. Trump presented a challenge to Republican leaders seeking to foster responsible behavior.

“On the mask side, it is difficult when the leader of the party had been setting a pretty bad example,” Mr. Hamer said.